The Final Chapter Revisited Twice: Power Records and Marvel/Curtis’ Battle for the Planet of the Apes By Anthony M. Caro

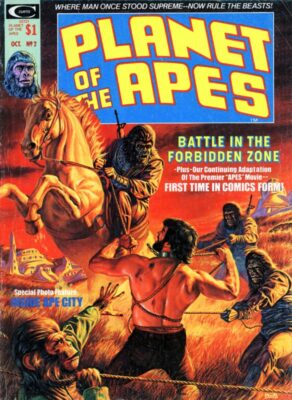

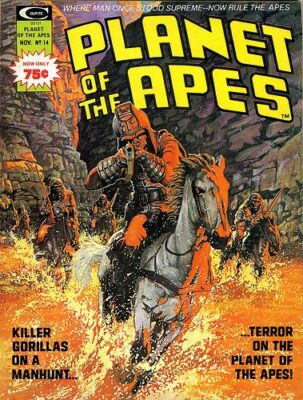

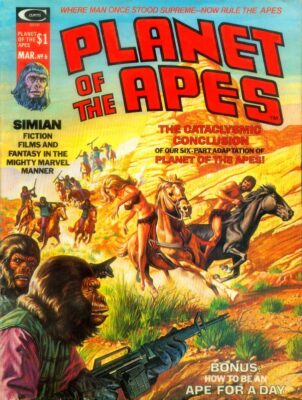

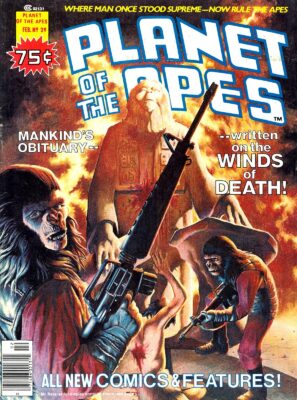

Marvel Comics produced many overlooked gems during the Bronze Age that gained appreciation decades later. Serialized adaptations of the Planet of the Apes films published in the Curtis Magazine imprint garner positive mentions from passionate fans. Writer Doug Moench’s ability to deliver thrilling reimagined versions of the films contributed immensely provided immensely entertaining material for the Curtis Planet of the Apes magazine.

Moench was even able to elevate the material when the series desperately needed some help at the end.

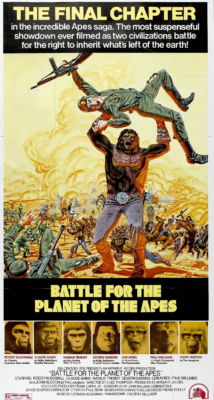

Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973) won’t become a film mentioned in accompaniment with words such as “polarizing,” “controversial,” or “debated.” While some fans and completists find merit, the overwhelming majority of collective critics and original series POTA aficionados bestow Battle with a simple label: “the worst.” Scores of troubles dragged down the inaugural franchise’s fifth and final entry, including a drastically reduced budget that turned the promised ultimate battle scenes into a pedestrian B-movie affair. Hindsight proved 20th Century Fox made the right call when cutting the budget. The $1.7 million feature only earned $8.8 million in the U.S., a figure that could not justify any further theatrical releases.

Battle never established firm footing or a desirable direction after its development phase turned decidedly rocky. Screenwriter Paul Dehn left the project due to health issues, and The Omega Man (1971) scribes John William Corrington and Joyce Hooper came on board to write the feature. The team never previously viewed a POTA movie, an odd decision since Battle’s storyline tied back heavily to the previous two films. Rewrites followed.

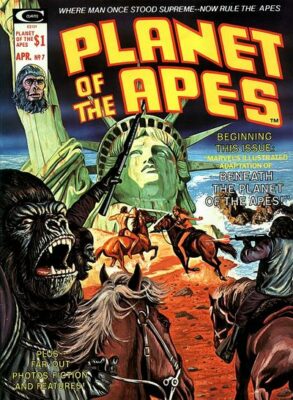

Premise-wise, the film served not only as a direct follow-up to Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972), it also acted as a prequel, of sorts, to Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), as the mutants from the second film make their simultaneous return appearance and timeline debut. The intriguing concept never lived up to its potential.

In the fifth and final entry, we find humans, mutants, and apes still in conflict with one another, just in a cheap, plodding way. The brilliant director J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone (1961), Cape Fear (1962), and Death Wish IV: The Crackdown (1987), unfortunately) returned after his success on the ultra-violent Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972). However, Thompson couldn’t inject the same vibrant, nee-compelling anger of Conquest into Battle, and the film fell flat.

The finished cinematic result left Marvel Comics’ Curtis Magazine imprint in a quandary. The predicament extended to Power Records, the legendary book-and-record company of Newark, NJ. Both companies found their creative teams tasked with taking weak source material into decent, sellable comic book adaptations.

Battle left a terrible taste in the audiences’ mouths when first released. Importing a “bad” film into a quality comic series seems like an unenviable but challenging task. Marvel’s creative teams rose to the occasion, delivering an excellent black-and-white magazine serialized adaptation. Disappointingly, Power Records’ attempt at a book-and-record radio theater production couldn’t breathe life into the tepid material and disappointed.

Monotony on the Planet of the Apes

Discussing the adaptations starts with discussing the source material and its discontents.

20th Century Fox’s decision to rush Battle for the Planet of the Apes into theaters to take cash from a dwindling fanbase doomed the release. Granted, in 1973, motion picture audiences usually shrunk with subsequent sequels, leaving only the diehard fans. Budgets dropped accordingly, but there’s no reason for quality or innovation to decline. Fox failed to take the necessary additional time to develop something intriguing to create a satisfying conclusion. The studio chose to make a fourth movie in four years, believing the big-screen franchise was marching to the graveyard. Why not take an immediate stab at one final cash-grab?

Battle does have some interesting allegorical themes about equality and morality. The prejudiced gorilla-out-of-time, General Aldo, and the mutant living in the past, Governor Krop, had the potential to become complex characters, but the dueling protagonists end up too one-note.

Does anything turn out worse than the (anti) climactic battle? The “last stand” conflict lacks thrills and massively underwhelms. Budget drawbacks led to the invading mutants’ numbers appearing too small to launch a credible challenge, and all parties, apes, humans, and mutants, move lethargically slow. Perhaps the slow movement reflects a sleight-of-hand attempt to make the mutant army larger and more menacing. If so, spectacular fail.

Fans, especially younger ones, did remain. Many children would experience the films for the first time long after their initial release, and older fans appreciated opportunities to relive the high points. 20th Century Fox knew the fans embraced merchandising deals, and comic book readers benefited from Fox’s licensing arrangements.

Peter Pan/Power Records Goes To Battle

Peter Pan/Power Records of Newark, NJ, started strictly as a plastics company and then moved into record producing with an eventual emphasis on children’s material. The company released numerous entertaining licensed film/TV show tie-in LPs and 45 rpm book-and-record sets in the 1970s. A once-popular and now lost entertainment artform, book-and-record combos presented comic books with a radio theater-style audio recording. Children could read along with the record as the story played out, changing pages after hearing a “beep.”

Adaptations of classic D.C. and Marvel Comics stories help “power” Power Record’s sales, as did other licensed properties. Star Trek, Space: 1999, and The Six Million Dollar Man catered to younger audiences who wanted a stop-gap solution when the reruns of favorite programs weren’t on TV. The popularity of Planet of the Apes continued to fuel various toys, games, and other merchandise items. Working an arrangement to release record album tie-ins made sense for the rightsholders. In 1974, Power Records released four different movie adaptations.

While Power Records would adapt previously published Marvel Comics’ stories, the POTA book-and-record sets reflected original in-house creations, predating Marvel’s versions. The original film, along with Beneath the Planet of the Apes and Escape from the Planet of the Apes, and Battle for the Planet of the Apes, weren‘t dumped into the market in 1974 and forgotten. The book-and-record sets remained in circulation into the early 1980s. Power Records would continue their POTA output with audio-only dramatizations based on the television series. Curiously, Power Records passed on crafting a Conquest of the Planet of the Apes book-and-record. Likely, the violent nature of the fourth film made it unworkable for the format and audience.

Unfortunately, the packaging did not provide any credits for the writers, artists, actors, or other members of Power Records’ creative team.

The first three releases were excellent, but Power Records couldn’t breathe much life into Battle. The Power Records adaptation does a fine job of getting across themes about violence, war, and racial strife. However, the story comes off as too abbreviated, and there aren’t enough compelling moments in Battle the film to import to the comic book/record version. Ironically, Power Records did an excellent job with Beneath, leaving out Beneath’s dull preachiness, opting to highlight the action.

Overall, the Power Records’ Battle adaptation casts draws further attention to the source material’s weaknesses. While the creators understandably had to cut down the narrative for time considerations, some plot deletions proved disastrous. Turning the Forbidden Zone mutants into mere humans and cutting scenes connected to the mutant’s nuclear strike ambitions prove quizzical. The book-and-record feels rushed and lacks the passion of the previous three works. Perhaps those producing the book and record had a low opinion of Battle. If so, it shows.

Planet of the Apes merchandise continued to sell in the early to mid-1970s, so Power Records likely did well with the Battle book-and-record. Any kid who read/listened to the first three installments would have a good reason to buy the fourth entry and an equally good reason to feel disappointed.

The Final Chapter(s) in [Curtis Magazine’s] Ape Saga

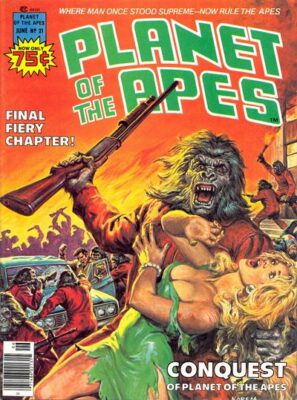

The Power Records version had already been in release for two years when Marvel/Curtis announced, “The Battle for the Planet of the Apes Begins!” with the August 1976 arrival of Planet of the Apes #23. Unlike the abbreviated Power Records adaptation, the magazine version spanned several issues and delivered a detailed and expanded narrative. The serialized version ran seven parts, ending with issue #28 (January 1977). Each chapter’s length was equivalent to a full newsstand comic, and, curiously, issue #25 (October 1976) featured two chapters instead of one.

The excellent Battle adaptation reflected the quality that enthralled the monthly magazine’s readers consistently. Unfortunately, the outstanding magazine would conclude with issue #29 (February 1977). Copyright issues prevent Marvel from releasing reprints or collected editions, for now.

Even the most ardent POTA fans know Battle represents the low point in the series. The weak box office returns and awful reviews did not wholly diminish revenues for 20th Century Fox, though. A new film did keep licensing rights alive, as the Curtis Magazine indicates. Marvel/Curtis, unlike Fox, could not afford the luxury of releasing disappointing material. Producing quality work was a must, but even exceptional stories could only do so much. The magazine lived and died by sales, and the decreasing popularity of POTA would drag the magazine down.

Writer Doug Moench and a collective of pencillers had to make the best out of their Battle for the Planet of the Apes adaptation. The art team featured Virgilio Redondo, Dino Castrillo, Marshall Rogers, Sonny Trinidad, Alfredo P. Alcala, and Vicente Alcazar, and all did a fine job. The creative team worked hard to elevate the source material. Everyone involved with the magazine put their best work forward and delivered an outstanding serialized comic magazine that contributed to POTA Magazine’s standing in pop culture instead of rushing a cheap licensed cash-in afterthought to newsstands.

Ultimately, the Curtis Magazine imprint could not outrun the inevitable. As mentioned, issue #29 served as the fan-favorite publication’s final issue and Marvel’s POTA’s swan song. The Battle adaptation did its part to contribute to a high-note ending. The serialization effectively used its medium to make the story compelling.

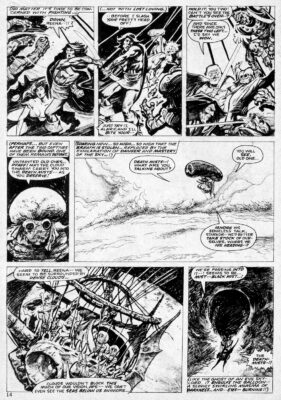

And the effective use of comic book storytelling did contribute many improvements. In the film, John Huston’s Lawgiver provides a prologue that seems somewhat tired. However, the artwork that launches the story makes brilliant use of black-and-white art and inks to recreate the introductory soliloquy. The various panel depictions of The Lawgiver draw the reader into the story, hooking the reader right at the beginning. Moench continues this approach by focusing heavily on character motivations and subsequent actions throughout.

Well-crafted film adaptations, be they in novelization or sequential art form, give the reader something “more.” The serialization delivers that “more” by fleshing out the characters and the story better than the filmed version.

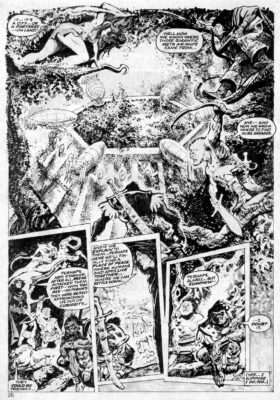

We see this when the work brings out “more” to the gorilla antagonist, General Aldo. He remains brutish, aggressive, and simple-minded, but panel descriptions present insights into Aldo’s character. We know what fuels his rage: he must live side-by-side with humans who once enslaved him. Aldo knows a revolution created the situation, and the humans would keep him enslaved had Caesar never led a rebellion.

The civil rights and class struggle-themed undertones hang over the relationship between apes and humans. The chimpanzees and orangutans treat humans humanely and with respect, but they do not provide them with equality. Humans have and know their place. Then, there is an unspoken truth: gorillas sit below chimpanzees and orangutans on the social order and must accept their limited position.

Is the current tense relationship what the future holds? We know things get worse, as a mutant/gorilla confrontation leads to the earth’s nuclear destruction in Beneath.

The main human character, MacDonald, pulls a sly sleight of hand to convince Caesar to travel to the Forbidden City and change history. Caesar will only hear about the future from his parents’ recordings, as the tapes feature commentary about the future from apes. Caesar won’t listen to a human, so there must be a dangerous journey to hear the same commentary from apes. Caesar’s internalized prejudices drive his actions.

MacDonald, trying to make a better future, inadvertently sets a course for a present-day war. He doesn’t realize mutants inhabit the city, and they are bitter survivors from Conquest furious about being deposed as the apes’ masters.

Once again, the produced film failed to effectively carry the narrative and its themes, leaving the action lacking dramatic subtext. The Curtis adaptation doesn’t suffer from similar missed opportunities.

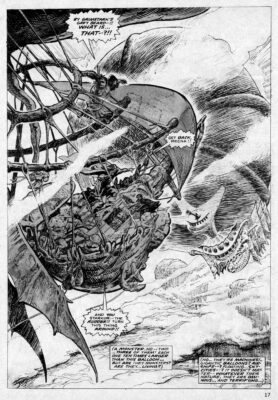

The adaptation’s overall narrative has an observational feel, as if someone watches the events unfold and carefully documents the action while providing personal commentary through the descriptive boxes. The approach pulls the reader into the story and never comes off as rushed or dull. The imperative nature of the plot propels the story. Battle for the Planet of the Apes focuses on a battle for the future. However, humans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and mutants all have different visions and preferences for the future; a thematic focus Moench expertly hones to create compelling drama and conflict.

The serial also corrects many deficiencies found in the film. See the artists’ renditions of the mutants’ appearances – the depictions show the mutants suffer terribly from radiation exposure, something not possible due to the film’s special effects limitations. The reader also discovers the mutants’ fear. They don’t want their self-contained world invaded, leading to their overreaction to Caesar, MacDonald, and the orangutan Virgil’s “invasion.”

Again, the focus on the characters helps the proceedings remain compelling. An intriguing touch not seen in the film involves Caesar’s loss of facial hair after traveling through the Forbidden City. The hairless face draws obvious parallels between apes and humans, showing they are not as different as they appear outwardly and inwardly.

Governor Breck’s character also comes off as more insane, and a brutal confrontation during the climactic battle sees the former slavemaster use a flamethrower to torture a prone Caesar while longing for his days of supremacy. Breck’s hatred drives the war, not so much desire to launch a pre-emptive strike to preserve the mutant city.

Moench clearly had access to earlier screenplay drafts. The flamethrower sequence appears in the final draft of the script, and it’s harrowing. The filmed version, which features a returning Inspector-Now-Governor Kolp instead of Governor Breck, has Kolp threaten Caesar at gunpoint. While less violent, the “cheaper” gunpoint scene lacks the dramatic punch. Moreso, Breck serves as a better villain than Kolp due to his greater prominence in Conquest, but henchman Kolp becomes the primary villain in the film.

Perhaps other elements from previous drafts made their way into the adaptation. Even if they did, the resultant serial reflects Moench’s vision of the tale. That tale leads use to the titular confrontation the entire film builds towards.

The battle itself sprawls over many pages and veers into “R-rated” territories of violence. The artists’ renditions bring the battle to its brutal life, and the writing conveys the necessary conflict and characterization needed to make the confrontation impacting and the ending more satisfying. The final panels also restore Corrington and Hooper’s original “playground fight” ambiguous ending, a much better finish than the film’s contrived final moments.

What made the whole adaptation succeed? Moench identified the finished film’s weaknesses, recognized the better elements of previous script drafts, and infused his own storytelling style into the finished comic version. His and the collective arts’ reimagining of Battle for the Planet of the Apes works on almost every level. The team created a “What could have been” sendoff to the first series’ final chapter, one that deserves an official reprint.

Anthony Caro writes about all things pop culture and contributed to HorrorNews.Net, PopMatters, Mad Scientist, Jiu-Jitsu Times, and more. Besides working as a professional ghostwriter, he handled production duties in radio, TV, film, and theater.

essay ©2023 Anthony Caro

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out our CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.

Images used ©Their Respective Copyright Holders