The African Prince by Alex Grand & Guy Dorian Sr.

Read Alex Grand’s Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland Books in 2023 with Foreword by Jim Steranko with positive reviews by comic book professionals, Jim Shooter, Tom Palmer, Tom DeFalco, Danny Fingeroth, Alex Segura, Carl Potts, Guy Dorian Sr. and more.

In the meantime enjoy the show:

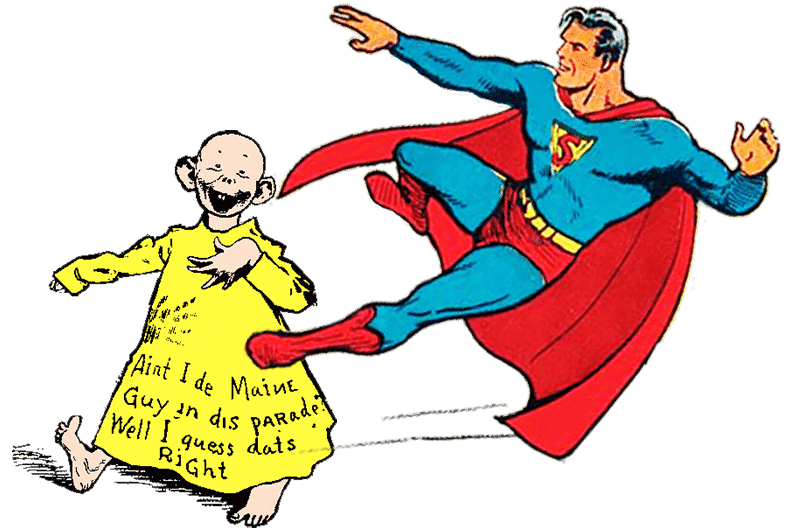

*Click above image to see video*

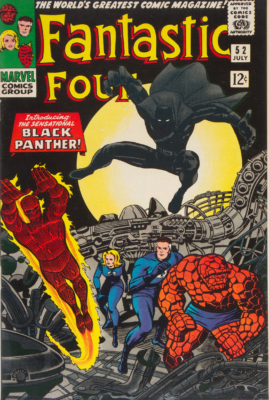

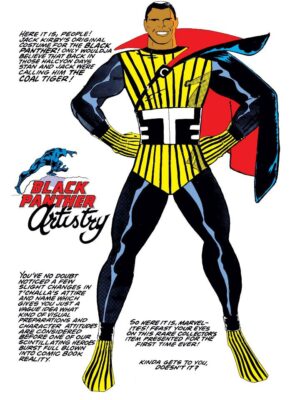

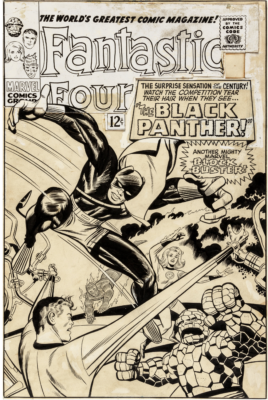

The African Prince T’Challa was created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby for Fantastic Four 52 (1966) as the alter ego of the first mainstream Black comic superhero, the Black Panther. The backstory to this is fascinating: After the king of the previously unknown yet incredibly advanced African country Wakanda was ruthlessly killed by the supervillain Klaw, the young prince and heir to his father’s throne takes on the responsibility to lead his people. Eager to prove himself in battle, he takes on the Fantastic Four and wins, overcoming the world’s premier superhero team, using both his enhanced physical strength and keen hunting intellect. This was published during a period of intense social unrest in the United States, and it was an especially brave step of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby as co-creators. Stan Lee as the editor and Martin Goodman as the publisher released the comic book, which hit the kiosk stands in April 1966. Stan and Jack committed with Black Panther to their tradition of inclusion after they had already introduced Gabe Jones in Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos (1963). During the 1960s, Black Americans sought social empowerment, as is evident in the formation of the Black Panther Party in October 1966. Looking back at this period in the August 2011 Alter Ego, Stan Lee stated that he decided on a Panther as a Black superhero because the animal was the helper to a Pulp adventurer. Jack Kirby also pitched a character who looks like T’Challa but was dressed as the Coal Tiger which was rejected.

An unpublished cover initially revealed the Panther’s black skin, but an editorial decision changed the costume to fully cover T’Challa’s body, thus leaving the surprise reveal for the interior storyline instead of giving it away before. However, there may be even more to the story of what went into Marvel’s Black Panther.

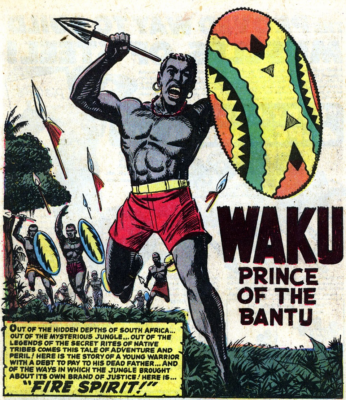

T’Challa’s backstory is that of a warrior prince who needs to pay a debt to his dead father. This has its origins in Waku, Prince of Bantu from Atlas’ Jungle Tales 1 (1954). The character’s first appearance, Fire Spirit (1954) was written by Don Rico with art by Ogden Whitney, and the opening page of the story reads, “Here is a story of a young warrior with a debt to pay to his dead father.” The tribesmen are identified as the Bantu, and the warrior is identified as the son of the dying chief Kaba. His father warns him to use a gentle and enlightened approach full of kindness to lead the tribe instead of brutal and overpowering warfare. Upon his death, Waku’s competitor Mabu fights and defeats other members of the tribe to become the new leader and lead the people into slavery while doing the bidding of illegal hunters. But Waku defeats him in a final battle to become the strong and noble leader of the Bantu people. Although Don Rico wrote this story, Stan Lee was editor-in-chief of the book, and we can assume he was fully aware of what portraying a Black hero in 1954 meant. If we now change the name Kaba to T’Chaka, Waku to T’Challa, the illegal hunters to Klaw, and Waku to T’Challa, it is very much the same backstory as Black Panther and his native Wakanda which Lee scripted and plotted with Kirby.

If T’Challa is basically Waku, then where did his alter ego the Black Panther come from? We are more likely to find this answer by first addressing how Marvel might have benefited from the name Black Panther versus Kirby’s Coal Tiger. It appears that a costumed Panther character was used in “The Panther Will Get You if You Don’t Watch Out” in Two-Gun Kid 77 (1965) in a Western bank robbery story written by Al Hartley and penciled by Dick Ayers. Stan edited this issue, and it is likely that this was a tryout character and – knowing Martin Goodman – a legal move to secure the Panther name for Marvel. This is likely because Goodman had nailed down trademarks of names from characters in his own company’s Golden Age like the Vision, Falcon, and Ringmaster as well as other company’s characters like Ghost Rider, Quicksilver and Daredevil. The Panther could very well have been one of these names where Goodman could very well have directed Lee who had directed Hartley to concoct a tryout character.

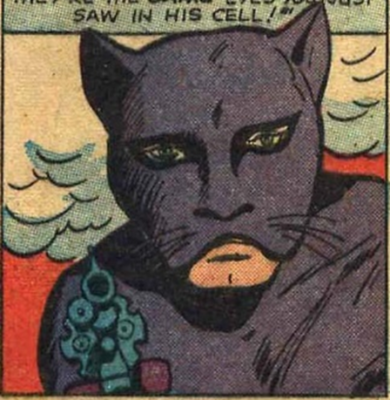

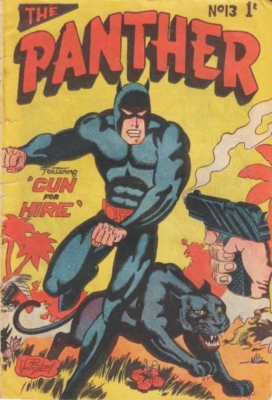

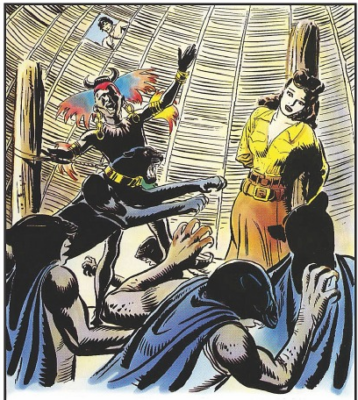

However, a Panther character would have had to exist from another company or from the Timely or Atlas era of Goodman’s comics for this theory be corroborated. This does, to an extent, exist in The Panther (1957) as a name used for a Jungle-genre character of a preexisting Australian comic book by Paul Wheelahan. Wheelahan was born in New South Wales in 1930 and was inspired early-on by Stanley Pitt’s Silver Starr comic strip to the point where he eventually became his assistant. Working under Pitt, Wheelahan was able to refine his technique as a writer-artist and eventually branched out on his own. Wheelahan’s original creation and mystery of the Belgian Congo, The Panther (1957) was well-received with Australian comic audiences, utilizing storytelling of both The Phantom (1936) and Tarzan of the Apes (1912). Wheelahan’s Panther superhero did also have a sidekick that was a panther as well, which could be argued to be what Stan Lee was thinking when discussing the “Panther sidekick.” Even more so, the first version of the Black Panther had the mouth exposed, which matches visually with the Wheelahan Panther. The acknowledgement of Australian comics was especially likely because Wheelahan’s cohort Stanley Pitt and Reg Pitt’s Gully Foyle received broad attention through the June 1967 Star Studded Comics fanzine despite the vast distance between the United States and Australia. According to the Kevin Patrick Goodreads blog, Al Williamson became a “big fan of Stan’s work on Silver Starr and showed copies of the Gully Foyle sample to Carmine Infantino and Dick Giordano at DC Comics.” This explains their art credit in DC’s Witching Hour 14 (1969) and Witching Hour 38 (1969) and ghosting for Williamson on a continuity of Secret Agent Corrigan. So, in the early to mid 1960s, it is possible that Goodman, who was always chasing genres and names, made it a point to secure the Panther name in the United States comic book market.

Martin Goodman could have also seen the Panther name sourced in another series, notably the Tarzan newspaper comic strip in 1951 which included a Panther Men storyline by Bob Lubbers. Lubbers was an American comic artist who had worked for Centaur and Fiction house before working on the Tarzan newspaper strip starting in 1950, taking over from Burne Hogarth. His run on the Panther Men ran from October 1951 to February 1952. In this continuity, Tarzan fought against the overpowering tribe at the peril of his love interest. Although the art is beautiful, this 1950s portrayal of the African tribesmen was generally derogatory; yet the usage of an African tribe in Panther gear certainly looks like a step toward the Panther tribe depicted in Marvel’s Silver Age.

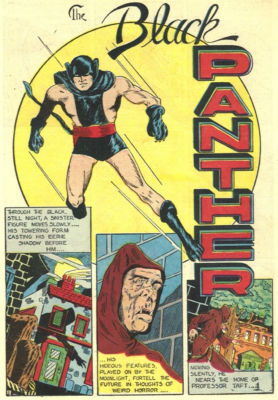

While Bob Lubbers was at Centaur, another creator by the name of Paul Gustavson created a character named The Black Panther for Stars and Stripes 3 (1941). This Panther appeared for only one issue and was a white man in a Black Panther suit who prevented a professor’s secret formula from falling into the wrong hands. Gustavson also wrote and penciled The Angel for Timely’s Marvel Mystery Comics 2 (1939), so there is a chance that Goodman could have known about this Black Panther character and wanted to secure another company’s Golden Age trademark.

When piecing together the origin of Marvel’s Black Panther, it is difficult to resist guessing who contributed what aspect of the character. Perhaps Martin Goodman directed Stan Lee to create a character with the Black Panther name. Perhaps Lee and Kirby then co-plotted elements of Kirby’s rejected Coal Tiger character and Lee’s recollection of the Don Rico’s Waku script into the T’Challa character we know and love today. During a socially awakened era like the late 1960s, Goodman, Lee, and Kirby likely felt they may hit a chord with readers by introducing an African (Black) character living in a high-tech world within the science fiction-rich landscape of the Fantastic Four. With all three creators no longer living today, it has become impossible to find absolute certainty in the Black Panther’s origin story, but Goodman’s behind the scenes directions to nail down names and genre’s certainly makes this storyline highly likely, if not very probable. It is certainly food for thought.

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out more Alex Grand & CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

Guy Dorian Sr., comic professional found here: https://www.facebook.com/they.bruce

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.

Images used ©Their Respective Copyright Holders