Roy Thomas Biographical Interview by Alex Grand

Alex: Welcome back to the Comic Book Historians Podcast. Today, we have a wonderful guest, a Mr. Roy Thomas, former Marvel Editor-In-Chief of the Marvel Bullpen. Essentially, Stan Lee’s protégé, also the creator of so many great things, especially in the late ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s over at DC Comics and more.

Roy and I have developed a friendship over the past 6 or so years, and he’s always so forthcoming with information about his career. I’m always so grateful. He’s also found a few of our interviews here at Comic Book Historians, fit to publish in his Eisner award-winning magazine, Alter Ego, that’s been around for more than 60 years. He actually joined us sometime back for a Marvel power hour interview which basically covered 1966 to roughly 1971. Today, he returns for a more comprehensive biographical interview featured now in Alter Ego 194 (2025).

Roy Thomas, thanks so much for being here with us today.

Thomas: Happy to be here. I saw some of the interviews that you have done with guys like Gary Groth, (Jim) Steranko, and so forth. I sort of enjoy this long-form kind of thing, so I thought it’d be really nice to be on here. Thank you for having me.

I should mention, we are broadcasting today from the Toucan Room, the Toucan Bedroom at our place. So, if you see all the toucans in the background… We used to have Toco toucans and of course, people gave us a thousand things, so we have a whole room. John Cimino, my manager, sleeps in this bedroom surrounded by several hundred toucan images [chuckle].

Alex: Now, we’ve done a one-hour interview before, sometime back. We talked about the late ’60s of Marvel, so I wanted to kind of talk about – before that, and also after that. So, I want to kind of start from the beginning a little bit. First, at what age were you when you started reading comics?

Thomas: I can’t really be sure but it would have been… Certainly no older than about four. Just from things I’ve traced back, in particular, a couple of the issues of All Stars and Green Lantern that I remember having.

But of course, I couldn’t read them for about a year. It took about a year or so to learn to read them. But I had a considerable vocabulary of reading by the time I entered the first grade, all of course, especially all capital letters was a little better.

My mother evidently saw… Or I spotted some on shelves. They didn’t have racks in those days. This was way back before comic racks at the local drugstore, at the time when drugstores carried comic books, and I must have seen them, and said, “What’s that?”

I know I was already familiar with Sunday strips and so forth. There was this photograph of me at the age of three, three and a half, in the Forest Park area near the zoo in St Louis, reading or looking at a Sunday comics feature over the shoulder of some guy, some stranger and my parents snapped a picture of us.

So, I was already interested in comic strips and then I saw these things on the stands that were sort of like them. It was probably a Batman or a Superman, but my mother had to read them to me for the first six months to a year. But I was so interested, of course, and as many people are in what was going on, that I’d learned to read. While I read other things too, comics were one of the things that got me started.

Alex: You started on kind of the DC material then, the DC Comics, kind of the national comic heroes, it sounds like.

Thomas: I know that about the time I was in the first grade, I was collecting some Timely or what was… Of course, nobody called them Timely Comics because…I remember I cut out, probably from some comic like Marvel Mystery, the Human Torch and Submariner were in but Captain America wasn’t then. And I had some…

Picked a lot of figures I had cut out of a comic, of those two characters, took them to the first grade. I was passing them back and forth with a friend of mine, who then wouldn’t give them back so I complained to the teacher. I didn’t understand you weren’t supposed to bring things like that to class, so the teacher confiscated them, and I never got them back. I’ve been traumatized ever since about losing stuff.

At that stage, I was not quite six when I began in the first grade, I know that I was at least buying the Timely Comics and other things by the time I was five, going on six. So, it was pretty early. Captain Marvel was in there too. A lot of different things… The DC’s weren’t my favorite – All-Star Comics, became my favorite the moment I saw it.

Alex: All-Star. So, is it because there was the whole crew of heroes in All-Star and that’s what gravitated you to that?

Thomas: Yes, I even remember telling some little kid… I don’t think it was my sister. She wouldn’t have been old enough… But somebody, explaining to it that what I liked about All-Star was the fact that all the heroes were in it together and they knew each other. I knew exactly what I liked from that moment and I was just disappointed there weren’t more comics like it. They never really put the Marvel characters together, you know, The Torch, Capt, Submariner together.

Alex: Based on what you’re saying, you’re finding these like at pharmacies and drugstores, a lot of the comics, back then. Were there newsstands around where you lived or was it mostly like drugstores?

Thomas: No, it’s a small town and Cape Girardeau, 10 miles away was home to maybe 15 or 20,000 people then. The four stores I bought most comics at, all the way through the ‘40s really, till the age of eight or ten or something, were the two drug stores in Jackson, Missouri. And two, what they called dime stores, a Woolworth and a place called Newberry’s which was sort of a minor league Woolworths. It was like two doors down, probably, in Cape Girardeau. Those were my sources.

About that time when I was about 10, there was a bookstore in Cape Girardeau, it had real books. That’s where I started buying a couple of books, when they started coming out, when I was about 10, and a few other books – Bomba, Tarzan, Oz, things like that, and they had some few comics. I could remember a few particular a comics I bought.

Alex: Now, you’re talking about the different kind of all-American comics that you’re reading. That was basically your favorite. You also had a predilection toward Human Torch, Submariner, and some of the Timely stuff, and Captain Marvel with Fawcett (Comics). But you also mentioned that you’re reading strips as well, comic strips. So what were some of your favorites? Were you reading Dick Tracy? Any of that stuff?

Thomas: No, I didn’t have much… Not counting what, by the time I was six, seven, eight, reading in reprints, where I discovered Milt Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates, and Dick Tracy, and things like that. I saw those mostly at the comic book reprints.

On Sundays, my dad would buy a St Louis paper, usually the Globe Democrat… I wanted to get Post-Dispatched, a bigger paper, because that had Pogo in it and other strips – Rich Guy and things like that. They had the better strips probably, but the Globe Democrat did had one strip, when I was nine or ten that I liked, King Aroo by Jack Kent, which was a real favorite. Still think one of the great underrated strips.

Don and Maggie Thompson, and I, and a few other people have always been champ for that strip. IDW did a two-volume collection of it, but it didn’t sell well enough to do a third. I was supposed to do the introduction for that.

But from the day, all I saw, six days a week; they didn’t have a Sunday edition… It was the Cape Girardeau newspaper the Southeast Missourian and the strips there, that I saw and got into… They stayed pretty consistent for a number of years. They were Li’l Abner, Freckles and His Friends which was kind of an Archie teenage strip. There was Boots and Her Buddies, which was kind of an imitation Blondie. Oh, and Alley Oop, which became a huge favorite of mine. I loved Alley Oop and still do, by V. T. Hamlin.

And then, in about 1951 or the end of ‘51 or ‘52, there was this science fiction strip that ran for a couple of years, it started there. It was six days a week. It turns out there wasn’t a Sunday until later. It’s called Chris Welkin, Planeteer by Art Sansom, this artist who later did The Born Loser. I really liked that. It was sort of like Terry and the Pirates go to Mars, I always thought it was be.

But that was about all I saw, except for a few things on Sundays. On the Sundays, I’d see some Dick Tracy or Prince Valiant, but mostly I had to be content with seeing those in comic book reprints.

Alex: I had read that you wrote your own comic, All Giant Comics? Is that right? And you sent that to your family members. How old were you when that happened?

Thomas: Well I didn’t mail it to anyone… Yeah, I would have been about seven, because of knowing where I got some of the ideas for a couple of the characters was from All-Star #… There were a couple of things based on characters of All-Star #38, where they fought history’s villains. I based a couple of characters on the versions there of Attila the Hun and Goliath as villains and made them sort of into heroes.

But since I was a little kid, I was short for my age, so naturally I made all giant comics. But my first comic, I’ve made a few copies of pages, was about… It must have been a 50… I think, when I last saw it, I only lost the last page.

It was an anthology comic, at the beginning and end was a character called Elvin Giant and there were four or five… All of them were giants, but they all had different angles. Some of them, some of them were always giants. I don’t know. It was just my little thing. All-Star Comics led to All Giant Comics.

Alex: Oh, I see.

Thomas: I did many others. A couple of years later, I made one, a Buck Rogers imitation called Buck Zzit, Z-Z-I-T, and things like this… I did some humor too. I had a character called Wizardo, a sorcerer who was a takeoff on… Did you ever hear of Pinhead and Foodini?

It was a Fawcett Comic based on a couple of puppets on, I think it was called the Lucky Pup. Some kind of puppet show. I never saw, but Fawcett did a comic for a couple of years. It was a wizard and his stupid apprentice kind of thing. I like the art and feeling it so I did my own imitation of that.

Then, I had King Cat and Prince Purr, which was a royal family kind of thing, and so forth, funny animal stuff. So, I didn’t just do superheroes. I did science fiction. I did occasional westerns. The humor of live action and…

Some of those were based on puppets too, because I got into making puppets by the time I was nine or ten. So, I would make up a puppet and then I would sort of license the rights to do a comic book of it. [chuckle]

There was a very popular show, Kukla, Fran and Ollie…

Alex: Yeah, yeah. I’ve seen that on YouTube. Yeah.

Thomas: Huge show on TV. Kukla and Ollie are puppets, and Fran (Allison) was a live-action woman. Well, I love that I didn’t have a TV then, but I would see it occasionally at my cousin’s place. They lived not too far from St Louis. So I would see, occasional episodes of Howdy Doody, Kukla, Fran, and Ollie, Tom Corbett-Space Cadet, when I visited them, which is very very seldom.

And so, I made up my own character, and I just took Kukla, Fran and Ollie, and I made up two characters called Cuckoo La Fran – new live-action woman and Ollie became Ozzo, who was a a sea serpent or a dragon or something. But it was just, you know, doing a little bit of everything. None of them were any good, but I still have a lot of that and some later stuff that I was drawing through my… Till around the time I hit teenagehood, I guess.

Alex: Yeah. So you were creative with characters from the beginning.

Thomas: The only thing I did after I was a teenager was one comic book, which I never quite finished but I did the beginning and ending of it. It had a great title, Marvel Comics [chuckle] and what it was is, I wanted companies to put together their heroes.

Submariner was still around even though The Torch and Capt had already died. We’re talking ‘54, ‘55 there. So when I’m 14, 15 years old, this is the last time I really tried to draw comic. But Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman were in it. The Blue Beetle was still hanging around at Charlton. Chuck Chandler who had been Crimebuster in Boy Comics and Slugger of the Little Wise Guys from the Daredevil Comics, and Submariner. Submariner because he was still around.

I put them together in a comic book called Marvel Comics #1, not knowing there’d ever been a Marvel Comics #1 as opposed to the Marvel Mystery Comics that I remembered. And I drew the first part and the last part, colored it and everything…

I was writing letters to the companies, trying to get them to put all their characters together and I figured, “Oh, it’d be a wonderful seller,” and so far they’d think it impractical… But I had a great name for the group that I made up. My JSA group composed of these multi-company heroes, it was called The Liberty Legion.

Alex: Oh, that’s great.

Thomas: And strangely enough, that was actually the second… A couple of years earlier, I’d actually done an earlier version with different characters that I made up. Some of them based on existing characters, called The Liberty Legion.

When I was in my early teens, I actually did two different superhero groups called The Liberty Legion which is why in the ‘70s, I had no compunction about calling a Marvel group, The Liberty Legion.

Alex: Did you also read EC Comics in the ‘50s?

Thomas: Yes and no. Mostly, no. I would see them on the newsstands, especially at a couple of stores like this bookstore that had some things. But I didn’t like horror comics and crime comics. Crime comics just didn’t interest me, and the horror-type of… First, I wasn’t really that interested and I had this feeling they would kind of disturb me, give me nightmares, and so forth. But I didn’t really like them that much anyway. So, it wasn’t like it was hard to give them up.

But what I did do is, strange, is I would go through them because I’d recognized that the writing was pretty good. I could read well enough to know that the writing in the EC Comics was fairly good and certainly really nice art. I could understand… I got to know who Jack Davis and (John) Severin, and (Wally) Wood, and these people were, even before I bought comics by them.

I would sort of skim them, and I would find that 10 or 20 years later, when I would meet somebody who had an EC collection, I would ask, “What about this story? What about that story?”. They would say, “I thought you said you didn’t read them?” I say, “Well, I saw it on the newsstand one day for 20 seconds, paging through a book and I remembered it years later.”

The first comic that I ever bought of EC was MAD Comics #5. I almost bought MAD #4 with the wonderful Superduperman story in it. And I’d seen the other three, but they didn’t get to me or they didn’t have in it what I was looking for. And when I saw Superduperman, I said, “Gee, they’re making fun of Superman and there’s Captain Marvel on top of it.” So I kind of put that down, but then about two months later, I picked this book up and it’s #5 rather, and it’s got the Black and Blue Hawks in it by Wood again.

Alex: Yeah.

Thomas: The Blackhawks weren’t as big as Superman and Tarzan, and some of the other characters MAD had parodied, so I began to sort of, appreciate the fact they were just going after everybody and I bought that. The funny thing is, at that point, I began to say, “Hey, you know that Superman story was probably good too.” And I was lucky enough, I found an old copy on the newsstand of MAD #4.

Later on, about a year later, the later Weird Science Fantasy, I think one of the first ones I ever bought was the Flying Saucer issue. Those were expensive though, those were 15 cent copies. See, I had to save my money for that.

Then I started buying Weird Science Fantasy, which wasn’t as much horror as the early Weird Science and Weird Fantasy had been, which I’d seen and that was a little more horror. And then, when they got to Incredible Science Fiction, that was nice.

But what I was a big buyer of? I was a big buyer of all the stuff that really sold lousy, like the so-called New Direction that they replaced the New Trend after the (Comic) Code came in. I bought Piracy, M.D., Psychoanalysis… Remember, Valor, Impact and what was the other one?… Aces High… Oh, and Extra! I bought all, every issue, of every one of those things even Psychoanalysis.

Alex: That’s funny.

Thomas: And of course, they died a horrible death very quickly.

Alex: Well, they had MAD after but… So now, I was looking up online on the GCD and we clarified this on email, but I want to just hear it from you also. There is a Phantom Lady #14 in 1947, and British Comic Eagle Annual #8, 1958 both are by Roy Thomas’ but those were not you, right?

Thomas: [chuckles] I would have been pretty precocious. No, I didn’t know about that other one you mentioned, but I do have a copy of a scan someone sent me of the one in Phantom Lady… And it’s not a name that nobody else ever had.

Alex: So now, in the late 1950s, and the early 1960s, there was this superhero revival, and Julius Schwartz and Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, all of the above, brought in a more kind of humanism to the superhero. More of a relatable science fiction relatable superhero kind of era, and especially in Marvel. Early Marvel geared more toward flaws, and realism, and what not.

So when that stuff was happening, how are you reacting to that, in real time?

Thomas: I got really interested from the day in 1956, when I went into the local drug stores to buy some fireworks, a day or two before July 4th that I saw Showcase #4. Here was a new version of The Flash and I got very excited about that. Even though it meant I’d probably wasn’t ever going to see the old Flash again. And of course, it took a two or three years, which seemed an eternity at the time, for them to publish enough issues that they would decide to revive The Flash.

Now, it looks back as if this all came very quickly – The Flash, then Green Lantern, and the Justice League, but it’s actually two, three, four years spread out between 1956 and about 1960 or so. And that’s a long time in a person’s life when you’re waiting two, three, four months to see a comic book.

I became very enthusiastic about them but they were really just this… Julie’s comics, I loved them… But they were really just the same comics that I had read growing up. I mean they were a little more sophisticated, the art was on the average a little better, and so on. But they were still aimed to entertain pretty young audience.

Marvel Comics made more sense, and Jack’s Fantastic Four…. As soon as I saw that, I recognized right away that this was a different kind of comic. It’s not like I’ve totally then threw over my liking for Julie Schwartz’s comics. I still like those but I realized that they had these things in them that… The arguing between the heroes on a serious level. The attitude toward costumes. The Thing wouldn’t wear a costume and they did the ones that wanted them to have a costume.

But the fact remains, you could see that they were trying for something different. It was not just an imitation. As much as I continued to love Julie Schwartz’s comics, I always bought them, very quickly, I realized that what Stan was doing with Jack and with Ditko, other people too, was on a whole different plane.

I don’t think I realized it right away. I think it sort of gradually came in on me over about a year or two, but I realized I was reading on two different levels. Kids can read them but they’re also… I could see there are a lot of other college students besides myself, and older people could have enjoyed them.

See, when I read comics by Julie, and I loved them, those comics in the late ‘50s, ‘60s. I always consider myself as sort of mentally slumming. Nine years old again, in one part of my mind. I knew those were the people that comics were aimed at and I was willing to accept them on that level.

When Stan started coming out with these books, it was like on a different plane, and I didn’t have to mentally slum to read them as much. I still had to accept some pretty weird stuff, and superheroes are kind of ridiculous by nature. It was still different. I was reading on two different levels and I can enjoy each of them. I retained this rather long-running attachment. I really got into the Marvel Comics too on a different plane.

Right after I got a job at DC, I’m writing a letter to Stan Lee at Marvel telling him how great the comic were. If Mort Weisinger had seen that, he’d have probably fired me off my Superman job [chuckle]. Because if there’s one group of comics about superheroes, I wasn’t interested in, it was the Superman group.

There I was working for them but I had no interest in them. I had to bone up by reading dozens and dozens of them in the month or two before I went to work because I almost never bought one, at that stage. They were really for the young kids as far as I was concerned. While they were intricate and well done in their own way, they just weren’t anything that was good for all 12 cents, I guess.

Alex: You started overseeing Alter Ego, meeting Jerry Bails. As you’re experiencing early Marvel Comics, you’re also getting involved in fandom. So how did that come about, editing and overseeing Alter Ego, in its beginnings?

Thomas: Well, I didn’t oversee Alter Ego’s beginnings. I was just a contributor really. In 1961, when Jerry Bails started Alter Ego, as a magazine, that old spirit-duplicated 14 paged, first issue magazine, he listed me as co-editor. But I was really just a guy who contributed stuff in Jerry’s four issues. I contributed the takeoff on the Justice League…

As a matter of fact, to show that, when Jerry had decided to give up, he didn’t even think about giving it to me. He figured, I wouldn’t be interested in taking over that kind of thing. He gave it to an artist – #5 and 6. And I, except for appearing in them slightly, I had no connection with them.

But then Ronn (Foss) decided, very quickly, in a period of a year that he was really an artist. So, he gave it over to another artist Biljo White. Again, primarily an artist, but also wrote his own stories. He was a fireman in Columbia, Missouri, so by that time, he and I knew each other. I went over to visit him at times. In fact, I first met Jerry Bails, the three of us got together at his home in ‘63, for a day or two.

Biljo was going to take over as the publisher editor of the magazine, which by now was photo-offset, at least. So we could print 500,000 copies instead of a small number. He was going to be Captain Biljo, that was his character, and I was going to be Corporal Roy. I was like the Robin to his Batman and he printed up flyers and sent them all out.

Then before a single issue came out or he did anything except star in a comic book story, he suddenly said, “I don’t think I really want to do this.” I sense he came to the same conclusion quickly that it took Ronn Foss a couple of issues to do.

“How about you take it over as editor and publisher? I’ll help you out by drawing whatever.” He was not thinking about publishing a magazine, but I did.

I took it over, that was in 1964, and of course, I did another few issues. A couple of issues or so, that I got into comics professionally. I’m just finishing up #185. So I guess, I’m kind of committed to it at this stage.

Alex: I never was able to ask last time, did you ever have any relationship or conversations with Martin Goodman ever?

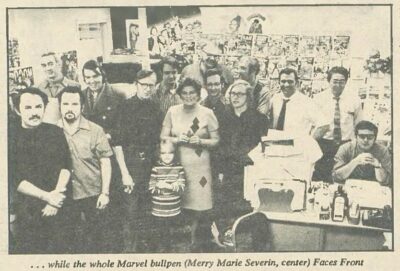

Thomas: No, about the closest I came was when Stan had me write this memo saying that we should get some character, and that was the first time I think I had any contact except there maybe, “Hello” to Martin Goodman who had an office way down at the other end of the hall.

Once in a while, he might have stuck his head in but I never had any relationship with him. He had once, when he went to Florida for over Christmas, he sent everybody a bunch of oranges. Actually, I didn’t get any, so I figured, “Okay he didn’t know me.”

Whenever I would see him later, for the next year or two, he would always mention this memo, this wonderful memo I had written about why we should do a sword and sorcery comic. I knew I was helping Stan out and writing some comics, that’s all he knew. So, I had very little relationship with Martin Goodman.

Alex: When you started writing with Stan and then writing a lot of that Marvel material, like right before you came, Larry Lieber was kind of helping Stan a lot. Then you kind of helped Stan with the writing. And then as you enter the ‘70s, you’re really the premier writer guy. You’re the guy that Stan looked to. Was there ever any tension between you and Larry Lieber over this or not really?

Thomas: He was only writing and drawing Rawhide Kid and occasional other Westerns. I don’t know, I don’t think he ever really wanted to write the superhero comics but Stan had got him to do it to help him out because Stan didn’t have time.

Stan became a little upset in the first Iron Man story, when Iron Man got knocked over by a filing cabinet or something that he has recently wrote. And it is true that right after that, Larry disappeared as the writer of a lot of the stuff, but if you decrease the frequency of a book Larry would quickly slow down. To me, he was a very slow artist and writer. Rawhide Kid was about all he could handle.

Alex: When Steranko first entered Marvel, around `65, around the same time you did, do you have any memory in him coming in and how he got into Marvel? Did you guys have any interactions in `65, when you guys both kind of showed up there?

Thomas: Steranko told the story of his hiring in the interview with you, didn’t he? How he grabbed hold of Flo Steinberg and made her take him in to see Stan?

I mean, I love Jim. He’s a wonderful artist, great racontur. Probably not a word of truth in that story, even if he picked this, because I was there. There was no manhandling of Flo Steinberg. Jim was going back and forth, sometimes he said he had an appointment, sometimes he said he didn’t. I really don’t know.

What I really know is that, whatever day it was… I don’t know if it’s a Monday, or a Friday… But it was after he had come to the 1966 New York Convention, which was held. He had an appointment, Stan didn’t want to honor it. Jim may not know this. I’m not calling Jim a liar on this, by any means. All I know is what really happened, and that is that Stan Lee told Sol Brodsky. That’s the way our chain of command was… To go out and get rid of this guy.

I knew Jim. I’d met Jim. I didn’t know him very well, but I knew him slightly. I didn’t even know anything about his artwork or anything. I knew he was this kind of a dealer.

I’ve had to brush this guy off to tell him, “It’s late in the afternoon, Stan just doesn’t have time.” I don’t know if he has an appointment or not. Nobody ever told me. So I go out, and I talk to Jim, and said, “I’m sorry, Stan really can’t see you today.” And Jim’s all kinds of unhappy about it.

Alex: He had a portfolio with him, right?

Thomas: If I had seen it, I’d remembered. I think it was that X character or whatever. It has some kind of nice curvy-ass Wood-ish kind of stuff. He has a motorcycle and there’s a lot of action. It’s two pages of that, and I’m looking at it, and I’m thinking, “Jesus, this guy’s good.” [chuckle]

Stan Lee shouldn’t be brushing him off. So I said, “Jim, wait.” Then I told Stan. I said, “I really think you should see his work. It’s really pretty good.”

So, Stan very reluctantly sighs, and says, “Okay”. So, we showed Jim in. Steranko did not force Flo, to ask her anything like that. Flo had no part of it. Obviously, I have no variation of what conversation was said between Jim and Stan. That part I don’t have any say. I’m just saying that how he got in to see Stan was not by manhandling Flo Steinberg, as he told you on the thing.

But he may remember it, maybe he’s confusing it with another episode… I found occasionally, I’d have two different episodes and I kind of put them together… You did this thing and that thing. And the next thing you know, you think you did something a little bit different.

I just know that Jim would tell people that I got him his job at Marvel, because I got him in. He’s gotten that now. Then he told people that Sol Brodski had got him his job. Now, he just decides he manhandled Flo,and he got in.

So, once he got in there, Jim was on his own. Stan could see how good Jim was. He always said I had a good eye for talent. I mean it wasn’t hard to see Jim Steranko’s talent. What I had to do was get Stan to take a chance on it, and Jim came out with an assignment. So, I felt pretty good about that.

I’m not going to let even Jim’s bad memory rob me that little tiny triumph of having that little tiny piece of Steranko’s favor along, because he made such a major impact on the comics field in that short time.

Alex: When you were there, there was an announcement made that Perfect Film & Chemical was going to come in and buy Marvel Magazine Management from Martin Goodman. What was your perception of that buyout? Was there ever any concern that everyone’s jobs would change or was it kind of business as usual on your end?

Thomas: It was pretty much business as usual. I think I was, and probably some of the other people, were a little apprehensive because as soon as you become part of a conglomerate even though Stan was lauding this, as being an improvement. “We have more money now, instead of having… DC had all the money and now we had a conglomerate behind us.”

But I knew that sometimes, conglomerates they don’t necessarily buy businesses to put money into they also just buy them to take money out of. I think that sort of what discontinued The Saturday Evening Post, if I’m not mistaken. And when that happened, that made us a little worried. If they could get rid of the Evening Post, what if Marvel Comics dropped a little bit in sales?

The weird thing too is that it was 1968 and that’s the year we turned all the books… Well, when I say “we”, of course, it was Stan and his decision, Goodman especially… Turned all the anthology books into their own separate titles. Tales of Suspense became Captain America and an Iron Man.

At the same time, there turned out to be kind of a downturn in sales, what’s going to happen? So, I think it was more a source of anxiety than it was of anything else. I don’t know about Stan. He probably went back and forth, he was a little manic that way.

He’d be real excited one day, and he’d be real depressed the next, when the sales went down. Because remember, he’d been through these bad times in the `50s. He’d been through the Wortham and senate hearing days. He’d been through the complete collapse of Marvel…

Even though my parents didn’t have any money or anything, I grew up in a situation where I felt, “Oh, the world was basically a good place, if we could just stop the Reds from blowing us up.”

Alex: When that was happening, Stan becomes publisher, when that finalized. You became editor-in-chief. How was that transition in duties? And was there some anxiety there? How was that overall experience?

Thomas: That came about in `72. But it all came about with situations that I knew nothing about. Stan was very discontented by that time with Martin Goodman.

Martin Goodman had made Stan promises when he signed the contract. Perfect Film evidently wouldn’t buy Magazine Management unless Stan signed a contract. Now, I didn’t know any of this at the time, Stan had a little leverage which he didn’t exercise. So, we’re just going on with business as usual.

He became increasingly unhappy under Goodman. And then came the worst, Goodman decided to retire after sticking around for two or three years, and I think Stan has some respect for Martin Goodman when he left. He still thought he was good on covers, even if he had practically destroyed the company.

I didn’t know this at the time but evidently, Stan began to look around for going to DC. I guess he held a meeting with some DC people once. Although again, he didn’t bother to tell his lowly assistant editor. He was just very unhappy, that I knew, under the people. We all felt that Chip (Goodman) didn’t know what he was doing with regards to the comics. We didn’t know about the men’s magazines necessarily.

So finally, one day… And he tells me, things have changed. The Perfect film company which was now called Cadence, was going to be the president and publisher of the Marvel Comics group as a separate company. We were going to have our own controller and several other people, so we had a higher payroll, so we suddenly had to put out a lot more magazines.

I was going to be his story editor – not editor but story editor. Stan didn’t like to give out titles. He had been always the editor. He had always been the art director. He didn’t want a full editor. He didn’t want somebody else to have the title of art director, so he took Frank Giacoia, a good artist, “assistant art director” even though there was no real art director at that stage.

Stan didn’t have the title, nobody else did, but we have an assistant art director but no art director. John Verpoorten, by that time, was in charge of production. So, we had this uneasy triumvirate. Stan didn’t like the covers Frank was doing, “He was too slow. He was this and that.”

And I was going to quit. I was really starting to almost make feelers to DC about quitting just because I didn’t like the fact that Stan refused to call me editor-in-chief and I was just there to do the stories, and to be his little troubleshooter. It just annoyed me and I hadn’t got much of a raise.

I’m talking it to my good friend Gil Kane. Gil had been an artist I admired and then he became a good friend after we worked on Captain Marvel together. So, by this time we’ve known each other well for a couple of years. I’m telling him, I said, “Gil you know, I think I’ve just going to quit. Part of my entertainment would’ve been feeling me out about coming over to DC. I just don’t like the situations, with three people…”

Gil looked at me and saved my life, probably. He just looked at me and he said with his usual voice, “My boy,” which he said to everyone. He said, “Just don’t do anything.” I said, “What do you mean?” He says, “Well, I say, look at the situation – Frank Giacoia, excellent artist, totally incompetent as art director.” “Yeah, that’s my view and I think it’s almost Stan.”

He said, “John Verpoorten, production manager, does his job well. Doesn’t have any interest in the creativity, he just wants to get the books moving. You and he don’t have any real problems, right?” I said, “Right.”

“So, you just keep on going along, and see… And everything will come to you.” I said, “Yeah, sure. Everything will come to me.” So I did.

A week or so later, it wasn’t any more than that, Stan called me and starts complaining. “Frank Giacoia, those are good covers but they were slow in coming and they just didn’t have the life.” But he was an inker and he was not the right person, just like Vinnie Colleta later was at DC.

So, he calls me and says, “You got to talk to Frank about this.” And I just said, “I can’t do that Stan, because you made us equals.” I says, “I can’t tell Frank what to do.” And he said, “You know, you’re probably right. Okay, from now on you’re the editor and Frank can go back to being an artist or something, or at least he’ll be under you, even as assistant art director.” That’s when I was given the editor-in-chief.

It sounded less like an executive. I didn’t like that executive editor kind of thing. From that time on, it worked okay, until I just decided to throw over the whole job. But at least, there was never any question anymore that subject to Stan, and as long as I kept out of the way of Verpoorten’s deadlines, I was in charge of Marvel Comics… But with Stan there. I mean the second banana to Stan is way down on the pecking order, but that was okay with me.

Alex: The relationship between the Cadence people and the creative people, was Stan basically the mediator between the Cadence corporate people and you guys?

Thomas: Yeah, we never really dealt directly with Cadence. I think Stan had no business sense at all. I mean I don’t have a lot, he would have none. I think it was all he could do to stay awake in meetings – make these publishing decisions, what books we should publish, this, that, and the other. He just wanted to give up that situation, but I don’t think there was any pressure for him to. He just wanted them vaguely affiliated with Magazine Management.

A guy named Al Landau who had a company that basically, it sold Marvel’s comics in Europe. Not as Marvel Comics but as pages of magazines. So, every time a foreign company published something from Marvel he was making money, so he was brought in as president.

Alex: From what I understand, you guys had a little conflict, you and Al Landau. There were certain things that he and Stan were thinking about, as far as with freelancers and staff that you didn’t agree with. That created a conflict?

Thomas: Too often, when he or Stan would dick the freelancer or the staff, maybe I was not enough of a company man… That the next thing you know, I’m sort of considered disloyal, not a company man. Even Stan, and that kind of got to him. He sort of understood it. It wasn’t entirely wrong. There was a certain amount of truth to it.

Alex: So, that’s why you quit being editor-in-chief, and how did Stan react?

Thomas: Well, Stan, because he wanted me to go on being a writer even though I wasn’t the editor-in-chief anymore. I said, “No.” I said, “I’ll be the writer and editor of my own books but I will not…” He says, “Well yeah, but you’re going to be seceded by…”

There was no editor-in-chief for about six months then, whatever anybody says. Len Wein was put in charge of the colored comics. If he was editor-in-chief, he was the editor-in-chief of the colored comics but not of all of Marvel.

Marv Wolfman was put in as the black and white editor and so forth. Stan said, “Well, these guys like you. They respect you. They’re not going to do…” I says, “Yeah, but what happens two months from now or three months, and they quit, and omebody else comes in?” I said, “No.”

Stan made quick decisions, a couple of minutes, he said, “Okay. You’re now the writer-editor.” That was renewed, so I did that for the next six years until 1980, when I left the company entirely.

Alex: Okay this is one thing I’ve always been kind of curious about. Is “the illusion of

of change”, there seemed to be a lot of character progression but it seems to slow down a bit as far as status quo changes. Was the “illusion of change” something that was started at a particular point in time with an intent for that?

Thomas: Stan actually used that phrase in a conversation. It couldn’t have been any later than 1968 actually, because Gary moved to the West Coast soon after that. By that time, I was called associate editor and Gary Friedrich, my best friend from Missouri who’d come there, he’s on staff.

Stan said, “From now on, I want you to be very careful. We don’t make any major changes in the Marvel Comics. You can give the illusion of change, but you got to kind of change everything back by the end of the story, over a couple of issues.”

What we figured out eventually was, the reason is that once Cadence Perfect Film bought the company, they were interested in the licensing. And if you change the characters too much or if you get rid of a character, or you change its status too much – have the character get married, have him go through this or that change. If you change them very much, all of a sudden, it might affect their marketability in the commercial aspect.

It took us a while to figure that out but we figured it. Well, this was not Stan, this was the conglomerate Perfect Film, it was still called, coming in and sort of giving Stan orders about keeping the character consistent so that you could sell a lot of merchandising.

Alex: Yeah, that makes sense, especially the corporate angle. That totally makes all the sense in the world now, that connection.

So now, as DC Comics started to go on the decline in the early `70s and Marvel starts to surpass it, I feel like a lot of your choices are what’s responsible for that. For example, tell us about creating the Kree-Skrull War with Neal Adams and John Buscema, you’re basically bringing different characters and parts of the Galaxy together in a science fiction opera. Tell us about creating that moment there.

Thomas: You were mentioning, my influence, I wasn’t out to do any of that. I just was out to be Stan’s number two guy. Being his editor-in-chief was a little like being the shop foreman sometime, in a way. It wasn’t the job that became under Jim Shooter and other joe later on, and the fact that Stan went out to California.

But just because you got to do something about the illusion of change, we could do things with villains after all. When Stan and Jack created the Kree in two or three stories of Fantastic Four, and the Skrulls had been around for a while – the super Skrulls and this and that, ever since #2.

It suddenly occurred to me that we had a few others too, but there were these two main races now, both of them from the Fantastic Four book. They were roaming around in outer space and we always know when there’s two powerful forces in the neighborhood or in the world, they’re either going to be best buddies or…

I just inclined to have them be swiped from the basic concept of the book I had read back in the `50s called, This Island Earth. Made it to a movie I did not like, but the book I did like, by an old writer who didn’t write much named Raymond Jones.

Neal had a strong story sense and I had the direction I was going but I hadn’t really thought about it very much. But once I had to be getting together with him all the time on the plots it just kind of coalescence. He had a lot of ideas of his own and I already knew where the story was going, so we just had a good time for those few issues, except for deadlines.

We made it something as a milestone at Marvel and I know a lot of that has to do with Neal’s artwork. But that’s not the only thing I think. It’s just that it took Neal’s artwork to really crystallize it. I don’t think it would have quite the same impact long-term if Neal hadn’t come in and done a few issues.

Alex: Yeah, and you guys have worked together on X-Men was also awesome. I love that material. It’s some of my favorite X-Men issues.

Now, tell us about Jim Starlin – encountering him, hiring him. Were you familiar with the stuff he had done in the fanzines? Discovering him and how did that come about?

Thomas: He was a guy who was influenced by a little bit of Jack Kirby, a little bit of Gil Kane. A young guy with a bunch of ideas, but I don’t remember that much about the process, except that I saw from the very near the beginning that this was an artist who was more than another artist coming in. I think I saw that much.

He showed me some characters he wanted to use in the book. One of them, I like this name Thanos, but that character is too skinny. “Make him a big character.” I was thinking of like Darkseid Knight. I said, “Make him a big bulky character. The guy named Thanos, he’s death you know, and everything.”

From there on, Jim took it, and the rest of it was all him, like the Warlock book that I let him take over. Well, I found it very interesting, but very soon I wasn’t the editor anymore.

The funny thing is when Gerry Conway took over for a few weeks for me in early `72, as editor-in-chief five or six weeks tops, he did a lot of digging in the sales reports and discovered the sales were bad. But it’s good comic as far as we were concerned, so they survived for a long time.

Of course, the interesting thing is nobody cares about The Golem now. A lot of Marvel fans wouldn’t even remember there ever was a comic called The Golem. But everybody remembers the Jim Starlin’s Warlock, that he revolutionized a certain area of comics with it.

Sometimes, it just takes a while for things to be recognized, a lot of people… I mean Jim Steranko’s S.H.I.E.L.D. book didn’t really sell that well. The meals of my X-Men and Doctor Strange by me and Colan… Things I think worth buying them because they were a little more sophisticated.

Gene Colan’s weird panel shapes in our Doctor Strange. Neal did the same kind of thing and Steranko was doing weird things, and I think some of the younger readers didn’t quite make that leap, so it took a while. Eventually of course, all those things I just mentioned are considered like some of Marvel’s high points, in the period. At the time, the books were canceled. No accounting for taste. All you do is you throw it out there, and if the readers like it, they’ll buy it. If they don’t like it, they won’t buy it, we come up with something else.

Alex: Now, tell us about like taking on Dave Cockrum because he was doing Legion of Superheroes, and he had done some fanzine work. Did you know about his Legion material when you guys hired him? Tell us about that process of him entering Marvel.

Thomas: That was near the end of my period there as editor. However, he tried to show me some characters once, they weren’t going to let him do for the Legion. Because he had an idea about a whole mess of characters he wanted to add to the Legion, and he showed me a bunch, and apparently, I don’t remember it.

One of them, it wasn’t the same character, but it had the name Wolverine. Of course, I didn’t need Dave or anybody else tell me what a wolverine is, I was interested in animals and zoology.

A few weeks before I quit as editor-in-chief in late summer of `74, this idea came up which I won’t go into and say, unless you want me to, bring back the X-Men.

Alex: And that was my next question is, tell us about that, and how that came about too.

Thomas: Well, I will then. I will [chuckles]… What happened was that I was very non-directive as an editor-in-chief. I was so busy. I had good writers, I let them handle the books, and if there’s something wrong, I’d call them, but that was about it.

A month or so before, I called Len Wein into my office and I told him, “We got a lot of Canadian readers. I’d like a Canadian hero.” And I said, “I want to call him Wolverine. He’s short because a wolverine’s a small animal.”

I remember Len had done some things with foreign accents and I said, “Well, see you try a Canadian accent.” That’s half a joke, but I think Len took me seriously. It’s actually, you just say the same thing and say “-ay” at the end, I think, was the Canadian accent at that time.

So, this president guy, Al Landau, who I did not like at all, who did not like me at all – two of us and Stan, and John Verpoorten as production manager, maybe (John) Romita was there, but I don’t know, but the four of us at least were there. And Al Landau comes up with this idea he says, “You know, if we had a bunch of international heroes, if we could just break even in the States, we could make money selling them abroad.”

Of course, he’s thinking of Canada but also England, maybe Brazil or Mexico. Translated some comics, something might have gone to Japan, South Africa, but he was thinking just in those terms. I wasn’t thinking any terms except just the idea of an international group of heroes. Immediately, it made me think Blackhawk. which was just a bunch of aviators.

The X-Men which had been canceled several years before, but had really been picking up in sales to the point where people bought reprint books for the last several years, based on Neal’s and my issues. I said, “We could bring back the X-Men, have one or two of the old guys stick around, Cyclops and somebody, maybe Marvel Girl.” Now, we’ve had a few characters that we could maybe put in, it was up to the writer Mike Friedrich, this revived X-Men.

We were going to use a few old characters. I had Sunfire who was Japanese and Banshee who was Irish. They could be used. Made a lot of sense to put him in there. So, I assigned… Mike Friedrich would be the writer and I talked to Dave Cockrum, “You’ve got some new characters here. You don’t have to use any particular characters.”

I didn’t make him use Wolverine or anybody else. Dave already had a whole mess of ideas, all you had to do was change them to internationals, some of them were meant to be aliens anyway. And I just turned them loose on it.

Unfortunately, since I left being editor-in-chief, when Len came on to be the editor he says he forgot that Mike was supposed to be the writer. But somehow Len ended up as the writer, and he worked with Dave, and they did the Giant Size X-Men. Although there was a delay, it didn’t come out for a while, and my name was no longer associated with it.

So, that original idea of the particular kind of country we’d sell, kind of got lost but the idea of the international X-Men State… And Dave Cockrum, I suspect his Wolverine face may have been the same, since Wolverine had always been masked with issues of Hulk. When he takes off his mask he probably had the face that Dave Cockrum had made up for his own Wolverine or some other face.

Dave Cockrum became a sort of after the fact almost co-creator of Wolverine with the rest of us. The X-Men really had so many different people involved with it but more than anybody else, it was when Chris Claremont took over, just a couple issues in, and once Chris took over, he’d worked first, with Dave, and then later with John Byrne… I mean that was what caused the rise of X-Men – with all due respect to Dave and John was actually Claremont.

Alex: You mentioned leaving the position of editor-in-chief. What was kind of the final straw in leaving editor-in-chief? And when you told Stan, was he disappointed? Was he sad of you exiting that position?

Thomas: Stan wanted to send me over to the Philippines to talk to the Filipino artists we were just starting to work with, who had been working for DC. Tony DeZuniga and his crew which included (Alfredo) Alcala and…

I didn’t want to go. I was trying to keep my marriage together. I didn’t like traveling. There was an insurrection going on in one of the islands anyway. I had no reason to talk to a bunch of artists. I wasn’t even an artist.

Carmine (Infantino) and (Joe) Orlando had gone over a couple years earlier. I was going to go like a good soldier but I didn’t want to. It turned out, I didn’t have to because of my nemesis by that point, told Stan, “That’s too much like giving Roy a vacation.” So, he vetoed the idea of my trip. I pray, “Oh, please don’t throw me in that briar-patch.”

The trouble is Al and I were in such different… Al I think, was behind a thing once where a woman, her name was Connie, who sold ad space in Marvel’s books. She came into me one day and she had been talking to Al before, so I knew he had a hand in it or suspected he did.

She had a wonderful idea, she says, “I got this great idea. We’re going to sell every right-hand page in a Marvel comic for an ad because that’s the page people want. They don’t want the left-hand page ads, they want right-hand page ads.”

So, I said, “Are you saying that you pick up a Marvel comic, and you turn, and every right-hand page in the book will be ads?” She says, “Yeah! That’ll make us a lot of money.”

“No.” I said, “It’s just going to be such a breakup, an ad every two pages.” “It’s a left-hand page you have to read anyway.” I said, “This is the worst idea, I shall fight it with every fiber of my being.” I never heard of it again, with me or anything said. But I think, that just made Al angrier because I think he was probably behind that.

So, the next thing you know, Stan and Carmine… This is kind of a funny story but they went out to lunch. I had just got back from the San Diego Convention where I’ve not even talking to tell people about how I was thinking about quitting. How I was just too busy, I couldn’t really be creative anymore, and I just didn’t like it very much.

And the situation with Al Landau didn’t help because Stan would side with Landau a lot because Landau was his equal. They had just kind of left me high and dry. So finally, what happened is Stan and Carmine went out to lunch…

Frank Robbins, do you remember Frank Robbins? The artist, he did Invaders, He’d done Batman. He’d done the Johnny Hazard strip. Good artist. He lied to the companies about what his rate was, in order to try to get a better rate at the other company. A time-honored tradition, I mean people always lie about how much they make if they can get away with it.

Well, Stan and Carmine, over a couple of drinks or something, at lunch – Stan comes back to me and tells me, “From now on, any time that Carmine or one of his editors needs what an artist rate is, you’ll tell him. Anytime you need to know from DC, you call, and Carmine or someone will tell you.”

I didn’t like that idea but I just kind of grumbled, and I went home. I wrote Stan a note saying that we’re really kind of ganging up on the artists here. And I finally said at the end of this little three or four sentence memo, I said, “I consider this to be immoral, unethical, and quite possibly illegal, and I won’t do it.”

The next day, Stan calls me and after he’s read it, he says, “Well, I guess you consider this your letter of resignation.” And I said, “Well, if you want to consider that, yeah it’s okay with me.”

I kind of had it with the job. I basically had a standing job offer from Carmine to write Superman; last thing in the world I wanted to do. So, I’m thinking in my mind, “I’m going to go over to DC as soon as I leave the office. I’m making the call.”

Stan says, “No, I want you to go on to write, so that we’ll get somebody else in that maybe follow orders a little better or something like that.” And that’s when I told him that I would take the job only if it was writer-editor. In the modern parlance, I reported to Stan. Len had no authority over me. Marv had no authority over me. Their successors would have no authority over me.

But I accepted Stan’s authority even when I disagreed with him. I did not accept the authority of anyone else. Anyway, it worked out okay for a number of years and when Jim Shooter came in, and he and (Jim) Galton decided on the writer-editor policy… Yeah, I just left.

Alex: And it sounds like Stan had a real special fondness for you to kind of give you a deal like that after not being editor-in-chief, because it sounds like he really valued what you had to give.

Thomas: We did have a respect for each other and a liking. We’d get really angry… and I’m sure Stan, at various stages, was really mad at me because I was causing him trouble with Landau and everything. And I got mad at him and I’ve seen some things, I sent letters to him that I’m just as happy that Stan didn’t see. 90+% of the time, I had so much respect for Stan that I really would have hate quitting Marvel especially since he was right there. All I ever wanted was to be his second in command. I never had any other…

It was a little easier to leave in 1980 when he had very little direct involvement with the comics anymore. But in 1974, he still did.

Alex: When Jack Kirby came back to Marvel, kind of in the mid `70s, were you part of that discussion? And then, I think you kind of worked with him a little bit toward the later end of his era in the later `70s. Tell us about any sort of interactions you had during that second Jack Kirby phase of Marvel.

Thomas: First of all, I got to say that since I was about six or so, I was a huge fan of whoever was doing whatever in Simon and Kirby. That those names on a book sure meant something to me, starting with Stuntman and whatever I saw.

Jack Kirby from Fantastic Four #1, in particular, and I think he’s the best superhero artist of all time and everything. But he’s not the 99% genius that made Marvel. He’s a good part of it, maybe he didn’t get enough credit, but he doesn’t deserve all the credit either.

So, Stan had been very upset when Jack left. The more so, since he learned about it when Jack called him one day and said Jack was leaving, which was not a nice way to handle things. He’s a nice guy, but he was no more of a saint than Stan or anyone else.

But after two or three years, especially with the failure in the Fourth World, Jack began to get kind of discontent again. And like many artists and writers are, it took me a while to be sure what it was, but it was obviously in 1974, a couple of weeks before I left that editor-in-chief job, I was over at the San Diego Convention. They told me I was the guest of honor, as Marvel’s editor-in-chief, and it was a great occasion for me. I got to meet, sit at dinner between Milt Caniff and Charlie Schultz. That was a big thing for me.

Jack Kirby and his son Neal, I don’t know if Ros (Rosalinda Kirby) was there. But he had a drink with me and wanted to talk to me. So, we sit down one afternoon, out on the patio somewhere, and talked, and Jack says, “You know, I’m just wondering how the thing you or Stan or whatever…” Obviously, Stan’s the main person, I’m just the middle. “Would feel about, I wanted to come back to Marvel.”

I said, “Well,” I said, “Jack, you must know Stan never wanted you to quit. He always didn’t wanted you to go. He said many times too, in private, in public, whatever. He would love it if you came back. I would too, but the important person is Stan.” I says, “There is one little tiny barrier which could pass and that is the Funky Flashman stuff.”

I said, “Now, when you made up this character, Funky Flashman, based on Stan’s Funky Flashman’s flunky…” This spirit of Jack who has done that, but it wasn’t a big deal to me. I actually think the name Houseroy was kind of funny this way.

I said, “Stan, was really hurt by that.” Actually, he was furious. He wasn’t just hurt, he was furious. I said, “So, we can get past this.”

Jack didn’t know what to say to that because Jack is sitting there, his son, I’m sitting there. There are at least three people at that table that know that it was not in fun. This was vitriol coming out of Jack. Whether it’s deserved or not, it was not “all in fun”. So, I just figured, the best thing to do is ignore it because Stan’s going to let him come back anyway.

One day, several months later though, Stan calls me in his office. He says, “I got to tell you.” He says, “It worked out fine.” He says, “Jack wants to come back.” He says, “What do you think about that?”

I said, “Well, get him back but don’t let him write.” Neither Stan nor I had felt that the writing could… It’s just our opinion, we do not feel the writing on the Fourth World helped the book at all. It needed something else, not necessarily Stan’s writing it needed more discipline of a different kind, to not be confusing the readers. We might have been right, we might have been wrong, that was the opinion we both had separately. And so I said, “Get him back but don’t let him write.”

So, Stan says, “Well, he says if he comes back he’s got to write his own material.” I said, “Well, then get him back anyway.” I said, “Jack should be at Marvel.” He says, “Well, that’s the way I feel. I want to see how you feel because there’s a couple of people out there…” And he’s dedicating the general vision of the bullpen, out there is Romita, (John) Severin and John Verpoorten.”

I don’t know who, I can’t remember who had said this and I didn’t even ask. He says, “There’s a couple of people out there who feel we shouldn’t allow Jack to come back.” And I said, “Well, they’re idiots.” If somebody doesn’t like it, they can lump it. And Stan says, “Well, I’m glad because I said people were confused by having these people be opposed to Jack for coming back to Marvel. I said, “Nah, they’re idiots.”

Anyway, so Jack came back and he was burned before. He didn’t want to be part of a team. He didn’t want the Eternals to be part of the Marvel Universe.

If he did Black Panther, he threw away everything that people liked from the Don McGregor run, which if Jack could carry it over, he would have brought them with it. But instead, he throws that over because he was never going to be taken advantage of or give a free ride to anyone again.

I tried to get him a little later because I was getting to do Vader’s covers and anything I could since they loved his work so much. And I came up with an idea that credited for plotting with his name first because that was part of the writing, the Fantastic Four.

He said, “Well,’ he says, “I’ll do that.” He says, “If you write out a plot that has these panel by panel, every panel described.” Because he’s so determined that nobody else was going to get a thought out of him. It was a reaction to the way he felt exploited. He was really overdoing it.

I’m thinking, it doesn’t take me but one minute to realize that if I’m going to get that kind of work out of Jack, I’m better off with Rich Buckler or somebody else doing the book. Because they’ll give me some thought. Jack Kirby was determined not to give me any thought, just artwork. And you know, Jack’s artwork was fine, if he was really the genius with his thoughts too and he was going to be acknowledged for them.

So, I gave up on that. But I did give him a chance to the last Fantastic Four he ever did. Because I started the What If book to keep myself busy without having to coordinate things with other editors and so forth.

I wanted to do a thing about – what if the Marvel bullpen had become the Fantastic Four? It’s just kind of a funny throw away issue. The idea was Stan would be Mr. Fantastic. Jack would be The Thing. I was The Torch, because I was blonde. And Flo Steinberg, who didn’t come along til ‘63 or `64, but still the only woman around, even though she wasn’t working for Marvel anymore. She didn’t mind, she would be the Invisible Girl.

Jack said, “Okay”. I let him do the plot and so forth. He was going to get credit for all this or whatever. When the thing comes in, Jack has double-crossed me. He’s taken me out of the story, out of my story, my concept, which I gave the original production manager of Marvel. Sol Brodsky had been the Human Torch.

For about 10 or 15 minutes, and maybe longer, I really hit the roof. I mean do I throw him off the book or what? Because I was a little cooler-headed maybe than Jack, and not doing things out of a visceral need to…

Obviously, I made a good choice because I didn’t come along until several years later before so neither did Flo but we needed her. But I said, “But Sol Brodsky had been around a lot of the time with FF #1.” As a matter of fact he inked numbers 3 and 4, and he had designed the Fantastic Four logo, that’s on the first issue. So, he actually was around, not as quite the production manager, but helping at that time. So, it made sense.

So, I just let it go as it was and it turned out to be kind of a good book. I’m very happy with the way it turned out. Except again, I would never trust Jack again, on anything. But I’m happy of the fact that I made it possible for Jack Kirby to draw what amounted to his last Fantastic Four story. I think it was kind of a fun experience. It gets reprinted a lot.

Alex: When you basically developed the What If Comics was that had some connection or inspiration from The Flash of Two Worlds with Julie Schwartz? Was it kind of like bringing a Multiverse to Marvel through the What If Comics?

Thomas: It was poorly inspired by my love of Earth 2 and the whole idea of the other dimension that had led to the Justice League – Justice Society team-ups and that kind of thing at DC. But there was another even more important factor, and that was this was made up just a few days after I stepped down as editor-in-chief.

Once I left, I needed some side ideas, I did not want to do books, if I could avoid it… I was doing Conan, that was fine. It’s my little universe… I didn’t want to do books where I had to go check with somebody about – what’s Spider-Man doing?

I mean I understood the need to do this I just didn’t want to do it anymore. I’ve been doing it for the last decade and I didn’t want to do it anymore. I didn’t want to have to check what the FF is up to or what The Hulk is doing. One was the Invaders, the new adventure with new stories and it doesn’t conflict with anybody’s continuity so I could do whatever I wanted. Kill off any character I wanted.

I didn’t want to not cooperate. I just wanted to put myself in a situation where I didn’t have to think about it… And if I’m doing Conan, The Invaders and What If, I don’t have to coordinate with anybody and that’s what I did. It worked out pretty well.

Alex: You were on staff writing and you were writing Conan, but then this whole idea of Star Wars kind of comes along. You had to basically convince everybody at Marvel, “Hey there might be something to this Star Wars thing.” And the reason why that’s so important is because culturally what Star Wars became, but also when I interviewed Jim Shooter, he said that it was you bringing Star Wars to Marvel that saved Marvel from the same kind of implosion that DC ended up having in in 1978 or so.

So tell us about, like what was it about Star Wars, and how did that come about, and why did you have so much faith in it?

Thomas: In `75, I was a big admirer of George Lucas’ American Graffiti, one of my favorite pictures through the years. So, I had a chance to have dinner with him in New York where our mutual friend Ed Summer, who ran the Supersnipe comic store and they were sort of partners in the comic art business.

I didn’t even have a plot yet or a lead character Starkiller, Skywalker, different things. I hardly followed the conversation because they really were not talking to me they were talking to each other at that point.

About the time I made arrangements to move to Los Angeles, but I was still living in New York for the next few months, I got a call from Ed Summer. He said, “I have a guy here who’s Lucas’ right-hand man for merchandising, his name is Charlie Lippincott. He would like to have dinner together and he’d like to talk to you about the Star Wars movie.”

I said, “Well, great! It’s a science fiction movie. I’d go see it anyway. I admire George Lucas.” We go have a meal… Charlie starts showing me these production sketches they call them, but they’re really full paintings.

I’ve done a couple of adaptations of movies at the time. We’ve done that Sinbad movie and we did Logan’s Run but they didn’t sell many comic books. Logan’s Run did okay but it wasn’t a big deal.

So, we weren’t really that interested, and I knew that Marvel wasn’t really interested in doing movie adaptations particularly. So, I’m just listening out of politeness at this stage. I mean I’ve been out to dinner with these guys. He wants to tell me the story.

I can’t even follow it. I mean the hero maybe Luke Starkiller… They were just starting to film in North Africa at the time. But still didn’t know was he going to be Luke Starkiller or Luke Skywalker… He starts telling me about R2-D2 and C-3PO. There’s Obi-Wan Kenobi, sounds like a Japanese guy, Han Solo and Chewbacca The Wookiee…

I said, “What? Chewbacca the what?” I can’t even follow this stuff. The drawings are pretty and I’m just thinking this is science fiction. I’m just waiting for him to finish this spiel and I’m going to tell him, “No. I just don’t see that I should be trying to talk to Marvel into doing this. I’m not the editor-in-chief anymore. It’s not my job. Maybe they’d want me to write it but I hadn’t really thought about it.”

And then, Charlie turns over what they call the Cantina sequence, which is the drawing of a still pre-Harrison Ford Han Solo about to slap an alien in a sort of a Mexican cantina-type bar. Maybe you’ve seen that painting. And there’s a couple of stormtroopers and other aliens in the background and I said, “Wait a minute! I’ll do it!”

Suddenly, I’m saying, “Yeah, maybe we’ll do this.”

He said, “Why?” I said, “I thought you were talking about science fiction, and science fiction doesn’t really always do that well in comics. We had tried a few things. I had done a couple of science fiction comics, they had worlds unknown, unknown worlds of science fiction. They hadn’t sold any books.”

But I said, “This isn’t science fiction. This is like a western in space, a space opera like the old Planet Comics and Planet Stories I used to read as a kid.” I said, “Action of science fiction back.” I said, “We might be able to sell something like this.”

So, I set up a meeting with Galton, the president, and we went in, Charlie and I. I started off and then Charlie took over. He had all these advantages – first it was free. Charlie’s idea was it’d help the movie maybe if we had several hundred thousand copies of one or two or three issues of an adaptation of the story coming out right before the movie. Not the whole adaptation which he thought might help the movie. It might need it because who knows when these things are going to be a hit or not. The only risk was if the magazine itself would sell enough copies.

Stan has always said, and this l ways threw me for a loop, he always said he finally went along with it because Alec Guinness was in it. Of course, Alec Guinness wouldn’t have sold a comic book of Streetcar.

And then, the trouble started with the circulation director, an otherwise really intelligent guy, who’ve done a lot of wonderful things. But he got this wild fur that we were going to take a bath on the Star Wars comic because he says, “You want to do it in five, six issues.” And he said, “Can you do it in one issue?”

I said, “Look,” I said, “If I’m doing it, it’s six issues.”

Anyway, so we did it and Howard Chaykin with a little ghosting help from Alan Kupperberg, and one or two other people maybe, did most of the heavy lifting on the stories for the penciling, and did a really fine job especially with the first issue they did.

But in the meantime, we continue to have trouble with the circulation director. The guy once again, “We’re going to take a bath on this comic book, on this Marvel comic.” By this time, we’d had two issues, three issues out because the only stipulation was we had at least two or three issues out before the movie. Marvel didn’t take a bath, and if they took a bath in money, it’s what they took.

So, in my case, it’s just a case of lucking out. I saw something that looked like Planet Comics and I thought maybe it might be a fun assignment to write. I really loved it until about two minutes after the movie came out at which time Star Wars quickly became a sacred cow.

I couldn’t have any of it. I was gone because I wanted to work with Conan because Conan creator was dead four years before I was born. I didn’t want to mess with George Lucas… Archie Goodwin took it over and did a fine job with it. I think he probably had a better feel for it than I had anyway, so everybody won. I got out of Star Wars. He got into it.

Alex: Because you brought these critical things to `70s Marvel that I think really, the trajectory was what it needed to come out the way it did.

Now, you mentioned why you left for DC and it was the end of that editor-writer arrangement when Jim Shooter and Galton kind of were planning the creative direction of the company. Looking back now and at the time, what was your impression of that relationship between Galton, Shooter, and Stan Lee to some degree? Did you kind of look at it as something that you didn’t like or was it something that was against your own creative sensibilities?

Thomas: Galton and Shooter, it wasn’t Jim Shooter. They tried to put all the blame on him. They had decided, and I can see their point, that they wanted to get rid of this writer-editor situation. To think about it from Shooter’s viewpoint, I wouldn’t have liked it either.

You not only had me independent of the editor-in-chief, but you had Marv doing that, and you had Len doing that until he left. So, I mean, I was doing Conan at Marvel. Len and Marv, they had to go through Stan practically, and Stan didn’t like that situation because he was moving out further and further from the creative areas.

So, I can understand why they wanted to make the change. They got rid of Marv about six months before me. Basically, what had happened is that when they came to me I said, “Look”, I said, “I know you got rid of Marv and I’m perfectly willing to go. I have other offers.”

But they said, “Well, why don’t you have your lawyer draw-up the new contract? Just take the old contract and fix the money.”

“I’ll be happy to do that. I’ll spend that $200. I’m going to make the change that from now on. I will not report to Stan. From then on, I was perfectly content that Jim Shooter was going to be the person I reported to. I didn’t mind that, as long as there was no other layer, as long as it was just Jim Shooter and I was under him, that’s okay with me. If you can’t accept the writer-editor position in that way, let me know, I’ll just go away. No hard feelings, no nothing.” And I said, “Because I know you did that with Marv.”

He says, “Well…” and this is a quote, “The way we treated Marv is not necessarily the way we’ll treat you.” Because he’s having me go ahead with something that I said I would not do unless it was okay to have the writer-editor thing in me. I had a guy, do what I spend my time, I spend the money.

I sent it into Jim Shooter and I get this thing sent back to me right away, saying that, there’s going to have to be another layer, like of another editor in between, that was very clearly in the contract. It wasn’t that I was under Jim. I was now going to be under another guy whether he was called, whatever he was called and I considered this violation of my understanding with Jim. So, I immediately called Paul, he was at DC and said, “I’m quitting Marvel.”

By the time I spoke with Jim, I had arranged a deal with DC where I would go to work for them as soon as my contract ran out. It felt that it was a brazen lie, and whatever other respect I have for Jim, I would certainly never believe them again. If they said the sky was blue, I’d go look out the window.

So, I just left and Stan meant to get me to stay, but in the end Stan did what he always did, which is he sided with the editor-in-chief. He had sided with me when I was editor, so now he’s sided with Jim.

I understood that. So, we had a little talk. Nothing was going to change.

It was probably a mistake from the point of view of my career because I think I attracted more attention at Marvel than I ever attracted at DC, despite the early success of All-Star Squadron and a few other books. But at the same time, something that allowed me for even six or seven years to write my favorite comic book.

Alex: Now, when you joined DC, you said that was through Paul Levitz and you had called him. From what I understand, that relationship with DC starts in `80-`81, there’s a three-year writing deal, from what I understand. They were heavily promoting your arrival the same way that DC promoted Jack when he arrived back in 1970. They were doing like 16-page insert previews of your stories. They were obviously very proud that Roy Thomas was at DC.

Did you have to read a lot of the DC Comics before you kind of started up there? How was that transition content-wise? I know you got to work on a lot of your beloved Golden Age characters from All-Star, but how was that transition?

Thomas: First few things they were giving me were a little bit of a problem because I told them I didn’t want to write Superman or Batman. So, some of the first thing they gave me was a Superman special about the Fortress of Solitude, a Giant Size World Finest that told all the different versions of the origin of the Superman-Batman team. I even threw in some from the old radio show and they had me do several Batman stories.

I didn’t want to do any of them. I don’t think I ever did a whole Batman story. I think I dialogued one, plotted another, and gave it to Gerry Conway to finish. I love those characters but I didn’t want to do them, for the same reason I didn’t want to bother writing Captain America or Iron Man, and get involved with continuity.

What I wanted to do was mainly create some new books. Justice Society book died in the implosion of what, `77-`78, so I thought of the idea of taking that Invader’s idea – the World War II thing, and make a tapestry out of all the characters of DC the old.

War is one of the few things the human race does well together. As a result of that, it made good comics. You take a worldwide war and you take the most powerful superheroes, you toss them into that war, and you get a weird sort of alternate history.

Now, in actual point of fact, a lot of other good characters that could have been JSA members… And I just felt World War II was beginning to diverge a lot more than it ever did once you introduce Superman as the Spectre.

I found a way to kind of keep them at bay, and that way, I could have a story where I could sort of follow history but it’s history with super, say in the Saturday Night Live. In the early days, they had a thing about what if Eleanor Roosevelt could fly? That was my version of what if Eleanor Roosevelt could fly. It sold pretty well and it got to almost 70 issues. If hadn’t been for that damn crisis of the internet world, it might be going still, and I’d still be writing it, maybe it would be up to 1943 by now.

They wanted me to do a Conan comic book or something like that. So, I was seeing if we could get the rights to another Howard character that wasn’t owned or licensed by Marvel. I thought of Cormac Mac Art who’s at around 500 A.D, and make it sort of a different version, a few more big cities and things.

And that would have the Howard name. But then my wife convinced me that rather than just do another Robert E. Howard thing, why not make up something different. She came up with this nutty thought one day: what if an Indian, an American Indian discovered Europe instead of the other way around and that’s was the birth of Arak Son of Thunder.