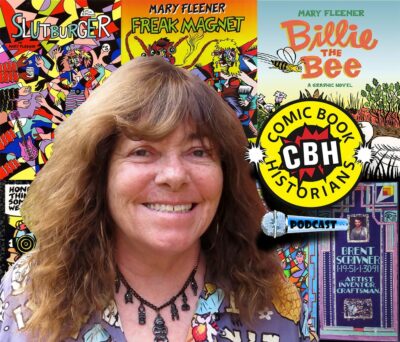

Mary Fleener Interview, Queen of Comic Cubism by Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

Read Alex Grand’s Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland Books in 2023 with Foreword by Jim Steranko with editorial reviews by comic book professionals, Jim Shooter, Tom Palmer, Tom DeFalco, Danny Fingeroth, Alex Segura, Carl Potts, Guy Dorian Sr. and more.

In the meantime enjoy the show:

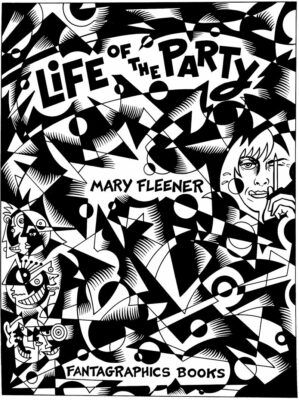

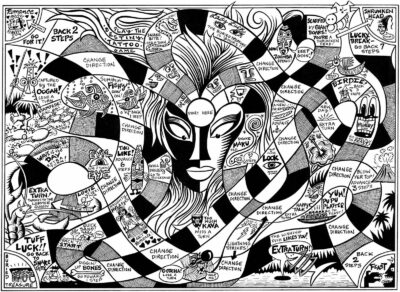

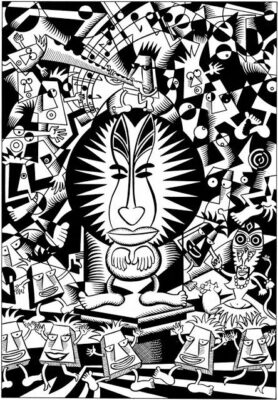

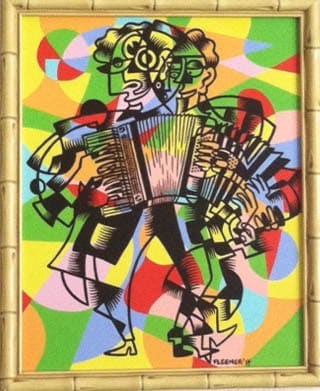

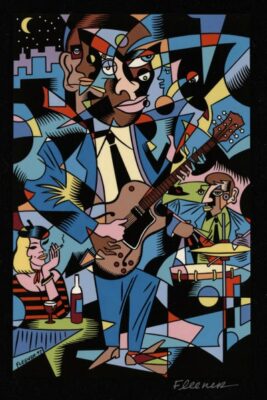

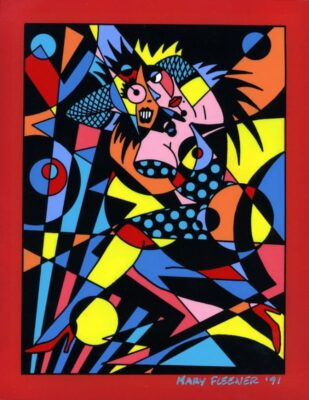

Mary Fleener is an American alternative comics artist, writer and musician. Fleener’s drawing style, which she calls “Cubismo”, derives from the cubist aesthetic and other

artistic traditions.

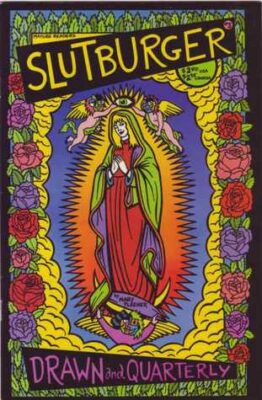

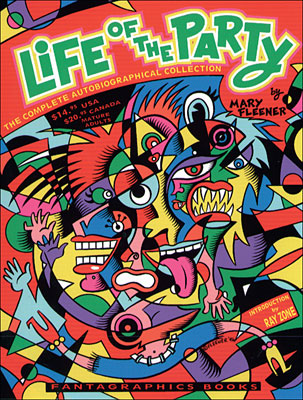

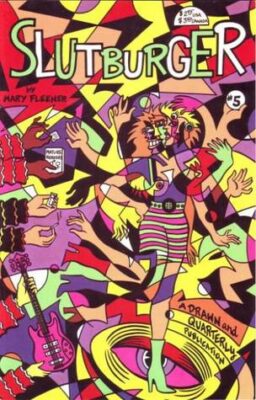

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview comic cubist queen Mary Fleener from her early days as a teenager reading Zap Comix, her first comics in college, joining Weirdo Magazine under editors Peter Bagge, Robert Crumb and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, producing Slutburger, Drawn and Quarterly, and her graphic novels including Billie The Bee.

🎬 Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Thumbnail Artwork, CBH Podcast ©2021 Comic

Book Historians.

Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders.

📜 Video chapters

00:00:00 Welcoming Mary Fleener

00:00:39 Early days

00:02:19 Progressiveness

00:03:31 Something missing in the United States

00:04:08 Influence of mother

00:05:37 Father cutting Little Annie Fanny | Playboy magazine

00:06:54 Harvey Kurtzman, Bill Elder

00:07:41 Comics strips

00:10:05 Pogo

00:12:46 Zap comix

00:13:52 Selling some of my art at age 15

00:15:20 Cal State Long Beach for printmaking | Roberta Gregory

00:17:53 My first real comic page

00:19:25 LA Weekly, Matt Groening | Robert Crumb, Dennis Worden

00:23:21 Music performances in gay bars

00:29:00 Drawing Power, Book by Diane Noomin

00:31:21 Chet Baker, Music interests

00:33:46 Chicken Slacks: putting lyrics into comics form

00:35:59 Grateful Dead comics

00:38:37 Weirdo, Robert Crumb | Mickey Rat’s Robert Armstrong

00:41:07 Influenced by art deco, ancient Egyptian art

00:42:05 Peter Bagge

00:43:39 Weirdo’s 3 different periods under Robert Crumb, Bagge & Aline Crumb

00:47:07 Madam X from Planet Sex | Autobiographical strips

00:49:00 Favorite Weirdo stuff

00:50:30 Turn Off That Jungle Music

00:54:35 Going to San Diego Comic-Con ~1986

00:56:51 Working Wimmin’s Comix

01:00:52 Women in comics | Comics Journal #237 cover

01:04:14 The Comics Journal | Trina Robbins, Marie Severin

01:08:04 Who was helping women get noticed and really emerge in the mid-90s

01:09:37 Twisted Sister, Diane Noomin

01:11:56 Hustler and Screw magazine

01:14:50 Influenced by dad’s Playboy collection | Gahan Wilson

01:15:59 Gloria Steinem

01:16:45 Autobiographical stuff: Life of the Party train, Slutburger

01:17:51 Howard Cruse, Stuck Rubber Baby

01:19:43 Drawing Power book, Kenny

01:21:24 I am a gun owner, but I don’t like it

01:23:10 AIDS Memorial Quilt, Brent Scribner

01:27:20 Like cartoonists more than fine artists?

01:29:24 You hate Los Angeles?

01:32:03 Single panel cartoons

01:34:30 Bongo Comics, Fleener

01:41:00 Harvey Pekar, The Beat | Diane di Prima

01:44:16 Popeye cover with the Bud Sagendorf re-prints

01:45:12 Kim Munson, Society of Illustrators

01:47:41 Silver Wire

01:49:00 Noomin’s Drawing Power

01:51:40 Billie the Bee, a graphic novel

01:58:30 Interested in doing more?

02:01:45 Life of the Party … Robert Crumb’s quote

02:02:32 Wrapping Up

#MaryFleener #Slutburger #BillieTheBee #ComicBookHistorians #WeirdoMagazine

#Fleener #Cubism #ComicCubist #ComicHistorian #CBHInterviews #CBHPodcast

#CBH #AlexGrand #JimThompson

Transcript (editing in progress):

Alex: Welcome back to the Comic Book Historians Podcast, with Alex Grand and Jim Thompson. Today we’re very proud to have Mary Fleener, independent comic book artist. In Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, Scott McCloud uses Mary’s work to explain non-iconic abstraction, and is at the top of his pyramid, alone and above everyone else. We’re very honored to have her. Mary, thank you so much for joining us today

Fleener: Thank you for having me.

Alex: Oh, yeah. We like to start from like the beginning of the person, like embryo stage, almost. You were born in 1951, is that right?

Fleener: That’s right. Up in Los Angeles, California.

Alex: Would you say you’re definitely a Southern Californian?

Fleener: A second gen LA native, my mom was born in LA too, and we’ve lived in California my whole life except for seven years, when we lived in West Vancouver in British Columbia. I was aged nine to 15. So, I ‘pubertized’ up there in Canada. [chuckle]

Alex: Yes. And I’m imagining both the embryo and the puberty in a cubist sort of way, right now. So, that’s great. So then, did that time in Canada give you almost like a different cultural outlook a little bit as well?

Fleener: Yeah, it really, really did. First of all, the educational system up there is way better than United States. I learned about things that we never probably discuss here, like the nationalism is not exactly a really good thing. Canadians had a bit of a superiority complex, where they thought they were better than the United States. Well, they are, in a lot of things. But they still had their racial problems with their First Nation people back then…

But anyway, all I know is… The school there was very tough. It was like England and they used corporal punishment. It was very English, but at the same time, very progressive.

Jim: That’s interesting that you say that. So, as far as the progressiveness and the people in the schools, do you feel like that rubbed off on you before you came back to the United States, or did you have a tendency toward that from earlier?

Fleener: No. For one thing, they push girls in sports. In the sports departments, there was no more money given to the football team than there was, girls playing basketball… So, that was promoted from grade five up to high school.

So that was something, when I came back to the States, all my events are gone. They didn’t have discus. They didn’t have javelin. In fact, the first school I went to when I came back was a Catholic girls’ school, they didn’t even have sports. They had no money.

But the thing was, when we did come back, I was so well-read and education was so good… I was done with math. I was done with English. I’d read all the books and so by the time I was a senior at Pales Verdes High School the last three periods were art [chuckle]… not even art, from lunch on till I went home.

Alex: That’s fascinating. So, you felt like maybe as far as women in society there was something missing in the United States in comparison.

Fleener: Well, there’s certainly something missing in the school system, in regards to girls and sports. And the teachers were all pretty butch, [chuckle] so that kind of put me off. And then I just went, “Okay I’m done with sports.”

But I got into art. That kept me busy. I hooked up with the art loser hippies at the high school and we…

Alex: There you go.

Fleener: Clung to each other.

Alex: There’s was a creative refuge there. Okay. So now, as far as your parents, your mom worked for Disney from 1941 to 1943. You said she was born in Los Angeles also. Did she influenced any of your creativity or foster it at all?

Fleener: Oh, absolutely. Not only did I inherit her genetic ability for art, but she let me use all her art supplies. That was one thing it was not off limits, and I destroyed pretty much all of them I didn’t clean the brushes and I didn’t put the paint’s away like I should have, but I never got in trouble for that. It was really strange. They were really strict about everything else but when it came to the art, that was fine.

She didn’t start doing art as a child, she was a child dancer with a group called the Meglin Kiddies. These little girls used to dance in the theaters before the movie came on… We’re talking 1925-26, something like that. So, she was really part of that Hollywood scene at a young age. Judy Garland and her sisters were in the same troupe. And my grandmother sewed all the costumes for the little girls, and my grandfather worked for the health department. So, we’re really LA people.

Alex: Yeah. Oh wow, that’s really great. So, there was a genetic, artistic gene, as well as the influence and the fostering your creativity. Then we also read that your dad also was into Little Annie Fanny so you got to see some Harvey Kurtzman…

Fleener: [chuckle]

Alex: From an early age. Is that right?

Fleener: Well he always had Playboy and he always had the dirty paperbacks on his side of the bed, which when parents weren’t around, we’d look at it and everything. And it’s funny because Playboy really wasn’t that raunchy. In the ‘60s, it was very intellectual, and the pictures were so tamed by today’s standards. It was just…

[00:05:00]

Fleener: My mom had big boobs, and I just studied art, and I’d seen all these naked people and ancient art. So big deal, right?

The Little Annie Fanny, it was just so well done, and I was already a newspaper junkie kid. Like when the Sunday paper would come, I would grab the comics run to my room, and nobody would see me for two hours. They’d be banging on the door, going, “Give us the paper!” So, they knew I really like cartoons and comics, and comic art. And of course, since my mom works for Disney, animation was okay. Most kids couldn’t watch Saturday morning cartoons, but we could. And so, my dad started… After I moved out of the house, he started cutting out the Annie Fanny for me, and giving them to me, so I could read them.

Alex: Did you get a sense of who Harvey Kurtzman was, at that point, or did that come later?

Fleener: No, not really. That was that was pretty much Bill Elder’s show. You mean, look at the art…

Alex: As far as the artwork, it is Bill Elder, yes.

Fleener: Yeah. So, when I finally discovered what Kurtzman did, I couldn’t believe it’s so loose. That’s not the same guy that worked on Annie Fanny, when in fact it was. But that one really shocked me when I finally saw what his artwork looked like.

Alex: Yeah. Yeah, because he was still doing the layouts for Annie Fanny, but illustratively, Elder… We interviewed Bill Stout and he told us that there was so much back-and-forth going on between Kurtzman and Elder in that, that it’s a really interesting… but also kind of watered down by half in some ways too.

Now, you were talking about the strips you were reading, so let’s go over some of those that. And these sound like they’re influences in a way. So, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, was that something you were into?

Fleener: Oh, absolutely. His use of black and white, nobody did anything like that. Nobody. And it was violent, and it was a creepy. I think it was a creepy strip for the newspaper, and there it was on the front page, every issue of The Herald-Examiner.

See, in those days, there was The Herald-Examiner and the LA Times, Herald-Examiner had a better comic section. And remember the comics section was like 24 pages, and the pages were 18 by 30 or something, the size of those big newspapers. I have a copy of the 1948 Herald-Examiner, and the variety of styles just was unbelievable.

I mean there was like Ripley’s Believe It or Not. Okay, that’s drawn in a real representational style. Then The Little King, The Little King was so minimalistic and so funny, and I liked it because it made fun of the kings. Because I was born an atheist and anti-authoritarian, I never respected authority… I mean you read history books and the kings are always terrible, and they screw everything up and everybody goes to war. So, that’s why I like The Little King, because they kind of poke fun at them.

Alex: Yeah, by Otto Soglow, yes.

Fleener: And then Li’l Abner, of course. I mean how could you not like Little… I mean, I know Al Capp was a creep and everything, but that Li’l Abner was terrific. It was unbelievable.

Alex: It was real comedy, yeah.

Fleener: And then the other thing about the comics is, there was lots of TNA. When I was a kid, Brenda Starr was sexy, and Moonbeam McSwine was kind of sexy. And then there was a strip called Long Sam and she was a mountain girl, hillbilly girl, and had the mother with the pipe in her mouth, and a shotgun in her hand. And guys are always getting lost on the mountain and they’d end up there looking at Long Sam, going, “Gunggg… gung…gung”. That didn’t run very long but that was pretty racy, for back then.

Alex: Yeah, that kind of stuff, also… Frank Thorne, we interviewed him once, he likes that kind of stuff as well. That’s cool.

Fleener: He was amazing.

Alex: Yes, okay. So, you’re a fan of Frank Thorne too – that’s cool.

Jim: Hey, Mary, one quick question, what about Pogo? And the reason I ask is because of I know how much you like True Swamp and Jon Lewis’ thing. And I read the Bee Book, and I can’t wait to talk about that. But was Pogo too late in time, or it wasn’t one of yours?

Fleener: Well, I had a lot of trouble reading, when I was a kid, and I kind of learned how to read by reading the comic strips because they had the pictures, so you could figure out the story from the pictures. So, by the time I was in the fourth grade I could not read. And my parents said, the teachers got together they went, “Oh my god, she’s been buffaloing us this whole time.”

[chuckle]

So, my dad had to tutor me at home. I get home from school and I was back in school again. And then after about three months, it clicked. So, for me reading Pogo was very difficult. The italic lettering bothered me because I sort of have a little bit of dyslexia, but they didn’t call it that back then… To this day, that’s why I could do printmaking because I can think backwards.

Jim: But you don’t like doing lettering to this day; that’s your least favorite part of doing comics. Right?

Fleener: Well, no, not really. I do like doing lettering, in fact, I like doing fonts and I’ve done a couple of covers for Mineshaft and I really got into finding the old fonts from the Speedball pens and once you get into it, it’s pretty cool. No, I just couldn’t, at that age, try to look at Pogo. The art was cute, but reading it was frustrating for me.

Jim: You have to translate it back into English, almost, from the thing that he’s doing with it. Yeah, I totally get that. That’s interesting.

[00:10:00]

Alex: Yeah, I actually still. I actually still have a hard time reading Pogo. That’s funny. It’s because the words sound like other words, and that kind of messes with me a little bit.

Jim: See, I’m a southerner, so for me, it was natural. I didn’t have any problem with it.

Alex: Right, because people actually probably talk like that. I see what you’re saying.

Jim: Absolutely.

Fleener: Well, I’m going to be honest, I’ve never really read a whole Pogo strip, for that very reason. So, when I was doing Billie the Bee, I got a Pogo book from the bookstore, and I started looking at it I had that same queasy feeling, like it was just so hard to look at. Hard to read and I kind of don’t get what he was trying to do, and I really should sit down one day and force myself to read it.

Alex: Now, we also read that you like Steve Ditko stuff, is that right?

Fleener: Not really. I’m really ignorant about the Golden Age stuff.

Alex: Okay, okay.

Fleener: We didn’t have comic books in our house.

Alex: Now, was Zap, was that an influence on you at all?

Fleener: Oh, absolutely. That changed everything. The cosmic wheel turned the day that… We’re all in high school and we had this one friend and he was a rich kid. And he had all the latest albums and all the stuff. So we’re going on to his house, we’re all going to smoke some pot, right? And he had a stack of these Zap Comix, so we started looking at them.

I’ll never forget that day. I can remember almost every minute of that day. And we never really did get to smoke that pot. We didn’t have to.

Alex: That’s cool. Yeah, like time froze and you just kind of memorized every moment of that.

Fleener: Well, the first time I looked at those jam pages of (Robert) Crumb’s, we all looked at that stuff and we went, “This guy is crazy!”

[chuckle]

Alex: That’s awesome. So now, is that right that you were selling some of your art by the time you were 15? Is that true?

Fleener: Yeah.

Alex: Okay. Was that at school or how’d that work out?

Fleener: Well there was a little shopping center near where my mom lives, and they had a little gift store. And I’d already been doing macramé, and embroidery, and all these kinds of arts and crafts that you do at school.

My mom went to some fair, and she came home with a wine bottle that had been painted like Italian style like flowers, and very traditional, and my brother had model kits. I thought, well I’d like to try that. And I found out the kind of paint you use; you didn’t use acrylic because I would peel off the glass. So, I started putting enamel and painting flowers on these wine bottles. My mom’s a big wine drinker so I had a bottle a day to work on…[chuckle]

And so, I started selling those things that little gift shop. And even back then, they took 50%, just like all the galleries do. But you know, every month, I have a check for like 40, 50 bucks.

Alex: That’s cool, yeah. Yeah.

Fleener: That was a lot of money in 1968.

Alex: Yeah, that’s right. Yeah.

Fleener: Of course, I didn’t save any, I mean I spent it on candy, and cigarettes, and records.

[chuckles]

Alex: That’s a breakfast of champions right there.

Fleener: Yes, that’s right, food groups.

Alex: [chuckle] Okay. So, you went to Cal State Long Beach for printmaking, like you mentioned. That was until 1976, and then Roberta Gregory was there at the same time. Did you know her then? Were your comics influenced by teachers?

Fleener: Oh, absolutely not. First of all, I did not know Roberta even though we were probably less than 300 feet apart. There was the illustration building across in the courtyard, and then we are the print makers on the north side.

I wish I had known her, and I wish I known Phil Yeh because he was there too, at the time. Because I went for four years to a junior college called Harbor Junior College in Wilmington. and I loved it. It was great. It was during all the hippies and all that kind of stuff. Then I went to Long Beach, and oh my god, it was just so lonely and impersonal. I didn’t make any friends and I didn’t make any boyfriends.

In fact, I’m writing my new book, the first chapter is about the last days of my life at that college before I just dropped out walked out the door… I actually left in ’75. In fact, I just finished chapter one, and I’m about to make that. It was just…

Fleener: I had nothing to say, I had no vision. I was taking 16 units. It was just too much… Having a friend like Roberta and a boyfriend would have probably kept me in there. And then I caught my teacher having sex with the TA in one of the galleries… And so, I was just like totally disillusioned. Like, “Oh, so this is how it works… “ I couldn’t get a job in the campus and I had no money. So, it was just a combination of things where I just said, “Screw this. I’m taking charge.”

I threw all my art supplies, and I got a job in a music store, and I said, “I’m a musician now. I’m done with this art trip.” I didn’t think I could draw any more, and what I was doing is poisoning myself with all these solvents: the nitric acid, the acetone, ink thinner, and stayed up all night. Doing all-nighters in the print room, and… I don’t know. I didn’t have a nervous breakdown, but I just said, “I’ve had it. I’m done with this shit.”

Jim: At the junior college, I read that that was where you used comics… I don’t know if it was the first time but you were using comics on those posters that you were doing for the ecology professor?

[00:15:04]

Fleener: Yeah! Well, what I was doing, I didn’t want to copy the comic guys but I really liked the whole attitude so I started to do these little things called Phallus Funnies, and they look like little worms but they were phallic shape. And I’d draw them out in the courtyard and trade them to people for joints.

[laughter]

Drawings for marijuana.

Alex: Oh, that’s awesome.

Fleener: Then my biology teacher, he wanted to start this new class called Ecology. That was a brand-new word, a brand-new thing, Ecology. So, he asked me to draw a poster for the class, and I still have it, but it’s so faded, you could barely see it. But it was done on a mimeograph machine and I guess that’s probably my first real comic page.

So, it’s a hippie with an afro in a poncho, and he’s looking in on a microscope, and all of a sudden, these little parameciums, the little mitochondria, or whatever they’re called, they start dancing around. They sing a little song about this class, and what time it is. And it was very, very underground influenced. So yeah, that kind of where it started.

Alex: Oh, that’s awesome. That’s really great. One more segue into what Jim’s going to go over, so you became a custom picture framer when you got out. You moved to Encinitas in 1981, still live there, and you started drawing little comics and letters you would send to your LA friends. One of those friends had you read new comics, a piece by Matt Groening, The Simpsons guy in the LA Weekly. How did that impact what you were doing in that stage of your life?

Fleener: Well that was another turning of the cosmic wheel, because the guy I was… Well, I was writing to a lot of people because I’d never written letters before. And so, we moved here in ’81, and I suddenly found I really liked writing. It’s weird because when I was in high school, I took one of those aptitude tests because I my grades are so terrible. My parents were just like, “She’s not that stupid.” So, I took these tests, and the number one thing it said I should be is, an artist and then underneath it was writer.

I’m like, “Writing? I hate English. Writing’s a drag… Ehh.. Phew…”

[chuckle]

I started writing these letters, and at the bottom, I’d put little comic strips. And one of them, I remember, I had a little black flea that lived on a white dog, and I call it Little Mofo, because I thought from the Angelfood McSpade, so big deal, right?

And so, this friend of mine Don Waller, he was in a band with my husband, they had a band called the Imperial Dogs. He worked for Radio & Record magazine. He wrote a book called The Motown Story. And we’re good friends, so he wrote me, and said, “Hey, you got to get a copy of this LA Weekly issue with that Matt Groening did, with the rabbit on the cover.” And I go, “Why?”

“Because, well, they’ve got this whole thing about underground comics.” And I go, “But they’re dead.” He goes, “Well, not anymore.” So, when I got the article, the first paragraph described me to a tee. Because, “Were you the kind of kid in school, instead of listening the teacher, you would draw, and then when she’d look at you, you’d crumple it up, that little piece of paper, and shove it in the back of your little desk…”

And I go, “That’s me!” Because if you saw the desks back in the day, they were like kind of hollow, you could put your books in there… Well, mine had about 8 inches of crumpled up paper, that was just shoved in the back. Because I would draw, because I wasn’t interested in school. I just wanted to draw.

Again, in West Covina, before we moved to Canada, it was like a hundred degrees there. So how could a kid concentrate with that heat? We didn’t have AC… Hell, the teachers are so badass they’d shut the door, and make you sit in even a hotter room.

[chuckles]

Because they’re so mean. They were mean.

So anyway, I get this thing and I get the address for Weirdo, Robert Crumb, Dennis Worden for Slur. There was a gang magazine called Teen Angel, up in East LA and then Raw magazine. I just go, “Robert Crumb’s address, oh my god!”

So, I wrote him, and he wrote me back, which was just like, “Oh, my gosh!” And then I wrote Dennis Worden, and it was amazing because he lived in San Juan Capistrano, and we became lifelong friends. He’s up in Medford now, but I think Stickboy and Dennis Worden’s work was just some of the best stuff. He’s really, really talented.

Fleener: Then when Crumb wrote me back, he sent me a copy of Weirdo #13, so that was like… It’s been happening… 1984. I think Weirdo started in 1980, if I’m not mistaken.

Jim: And that’s going to be the next comics section that Alex is going to do. But I wanted to go back to high school first and talk about music. Because you have twin artistic avenues and I didn’t want to leave that part out. So, if we can, I’d like to go back to high school, and how music was impacting your life at the same time; both as a performer and a listener.

Fleener: Okay. Well, it actually started when we lived in Canada and I was 14 years old. I was totally into Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones. And folk music was kind of still popular but up in Canada it was Ian and Sylvia, and Gordon Lightfoot. It really wasn’t like the protest stuff like Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, although I really liked that kind of stuff.

[00:20:05]

And a couple of my girlfriends wanted to form a band and they go, “Well, you can’t be in the band unless you learned guitar.” I go, “Yeah, good points.” [chuckle] My brother had a guitar and he has no musical ability, he has no artistic ability. So, he gave me the guitar, and it was a funny guitar because the strings are like about an inch off the fret. You just really hurt your fingers but I was determined. I started practicing, and then we moved away from Vancouver back to the States, so I was kind of on my own for about a year. So, I just practiced, and practiced, and practiced.

At the school, I went to St. Mary’s Academy, at noon all of us future rock stars, we’d get together in the art room and we played Monkees songs, because The Monkees were really hot back then. I didn’t like The Monkees, they were a band that was a fake band but boy, they were really popular.

Anyway, I finished one year in that school, and then I ended up at Palos Verdes. Then I really got into doing the hootnannies and being the head of the folk club. It wasn’t really a folk club. We all wanted to play Frank Zappa but we had it called the folk club.

[chuckle]

And so, I started doing the hootnannies and by that time, I didn’t really want to do folky stuff. I got into the music of Shel Silverstein… He’s the guy that did, I’m Being Eaten By a Boa Constrictor. He wrote a Boy Named Sue, and so we used to do this song called You’re Always Welcome in Our House. And the lyrics are basically, a little kid goes into a yard and they abduct him, and seal him inside of a wall, or they eat him, or something. It’s really dark, but I thought it was funny. So, I was into Shel.

Then I didn’t start learning electric instruments or electric bass, until I was like 24. I got a job in a music store, and so then I was able to buy an amp and all that stuff, and really concentrate on playing an electric instrument. But I started out with an acoustic guitar.

Jim: Were you forming bands with your friends?

Fleener: Not in high school. In high school, bands were a boys’ club. There wasn’t a guy there that would have a woman in a band. It just wasn’t done. So, when I started learning bass, then I started jamming with guys and people that I knew that… Yeah, a lot of change from 1969 to ’74.

I guess the first band I was in was a Chuck Berry tribute band. And so, I learned a lot about 12-bar blues for being in that band. If you’re going to play rock and roll, you got to know 12-bar blues. [chuckle]

Then after that… I mean, when I was in a band, all I did was sing harmony and bang a tambourine. But then about 1975, I met a woman who played keyboard, and we started playing all the gay bars in Orange County along Garden Grove Boulevard. So, that’s what this new book is about.

Jim: You’ve done some… I’ve read some of your comics about that experience.

Fleener: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I covered that but not to the extent that I want to talk about it now. Because the kids that are young adults now are lucky because they can be the gender that they want to be, they can express a sexuality they want to. But boy, back in the ‘70s, if you said you were gay, people thought you were a child molester. And a transgender, I mean my god, if you walked down Garden Grove Boulevard in drag, you’d get murdered but, that was weird, in that Orange County area there are more gay bars there, and then there were up in Hollywood.

So, for about a year and a half I played every Friday, and Saturday, and Sunday from 9:30 til 1:30 in the morning, and that’s how I paid my bills.

Jim: Oh, that’s great. I love those stories, some of them, about those early performances you were doing, like even the first night you were performing there in that bar.

Fleener: Oh, there was a big fight.

Jim: Yeah, the big fight, the crazy drummer, the big fight then the party at your house when you go back. All of that. That’s a good story. So, I look forward to the new stuff.

Fleener: Well, it’s going to be even more get down because I’m not afraid to talk about… I’ve been saying this lately, when you go back in time, and do stories about things you remember, it’s like walking through battery acid. Because you’re like, there’s a lot of painful things I’m trying to talk about that I was afraid of talking about. But after I did my story for Drawing Power the book that Diane Noomin edited.

Jim: I read that this morning. I read your story there, this morning. I want to talk about that because that was very powerful. It’s weird, I was madder at the old boyfriend than I was at the rapist basically. And I know that’s how you set it up, but it was a really interesting story. And I can’t wait to read the whole book actually, and the different contributors. But I read yours, in researching this, and that was that was great.

Fleener: Well, I’m glad you got it, because I hadn’t wanted to write about that story. I didn’t want to talk about it. My husband didn’t know what had happened to me. And then my friend betrayed me, I go, “Now, I got a story. [chuckle] Now, I got a story.” Because if anything illustrates the Me Too Movement, it’s when people say things like that.

[00:25:03]

“Well, why did you go on that date? What were you wearing? Why were you drinking? What were you thinking?” And that’s what really hurts. It’s almost like, it was your fault.

Anyway, we went through a lot of different drummers. We went through three different drummers, and one of the drummers became a very famous punk rock guy named Nickey “Beat”, who ended up playing with The Weirdos, and The Cramps, and The Mau Mau’s and L.A. Guns… So, I talked to him. I found him on Facebook, and I haven’t talked to him for 40 years.

It’s kind of neat, like doing the research for the Bee Book, going back and talking to these people that I hadn’t talked to for a long time. I wanted to let him know what I was doing, I said, “You’re going to be in my book. Is that okay?” He was like, ”Yeah, yeah, you could use my name and everything.” And I’m like, “Well, maybe. We’ll see.”

Jim: You were playing certain kinds of music, but you had a pretty wide range in terms of your interest. You’re like a Chet Baker fan too, right?

Fleener: Oh, I love Chet Baker.

Jim: Me too. He’s one of my favorites in terms of that.

Fleener: Oh, yeah.

Jim: So, you weren’t limited. You were exploring everything in terms of music. Was that going back to early days?

Fleener: Well, yeah, it was actually because, when I was like in the fourth grade, I really like this woman named Dorothy Provine. She was a singer on a show on TV called… Oh, what was it called?… It was a gangster show… It was called The Roaring ‘20s. It was about a bunch of guys, a bunch of cops, trying to fight the mob. Every show, they’d have a nightclub scene and she’d be the act. And she’d sing all these songs like I Want to be Loved By You and like ‘20s stuff. I just thought that was so great. My mother thought I was out of my mind, she goes, “That’s old music. How do you like that old music?”

But it was terrific. So, I was never just rock and roll. And then when I became a teenager, I rejected rock and roll, and I start getting into jazz. I was really lucky I got to go to The Lighthouse, I got see Bill Evans, I got to see Mose Allison, I got see John Handy. I was 18, so I couldn’t drink, of course, but you could get in the clubs. So, that’s what I did. I really got into jazz… My favorite was Miles Davis, of course. But I saw him at the Hollywood Ball, and he was so into cocaine… Oh my god, he’d come on the stage and go, “Honk”, then he’d leave for 20 minutes. Then he’d come back go, “Honk… honk.”

[chuckles]

Fleener: Then he’d leave for another 20 minutes. I’m like, “Ah, man…”

Alex: That’s priorities right there. You got to love.

[chuckles]

Fleener: Ah, geez… And it was all that fusion crap. So, I saw John McLaughlin, Tony Williams, Stanley Clarke, and they were the most boring concerts because everybody was trying, “Fusion… Fusion… Yeah, it’s really great.” Uh, god.

[chuckle]

I saw them all.

Alex: I liked your commentary, that’s cool. And your commentary feeds into your comics, so it’s cool actually, verbally hearing it as well. It’s awesome.

Jim: I wanted to segue into that because, I know they weren’t published until a little later, but when did you start doing like this Chicken Slacks stuff where you were putting lyrics into comics form?

Fleener: The first time I did that was for the that little zine that they put out for WFMU. It was that station out… Where’s at… New Jersey, was it? Well they had a little, either every month or every other month, a program guide and they hired a lot of people like Kaz, and yeah, all the Raw and the Weirdo people to do artwork. And they paid pretty well, so they wanted me to illustrate Golden Birdies by Captain Beefheart, and so that was the first time I illustrated a song. It was just like, “Oh, this is so right.” [chuckle] Because rock and roll songs are little stories, right?

Then I did Signed D.C., I think that was that song by Love, and Arthur Lee wrote that. And I forget what the year the first Chicken Slacks was… The first issue was just sort of anything anybody wanted. But then we had a psychedelic issue, we had a soul issue, and then a punk issue… So, that 1988, and everybody donated their art.

Except for the psychedelic issue, I made some money in a… Well I won’t tell you how I made it but you can guess… So, I was able to pay everybody 10 bucks a page. And it’s a psychedelic issue, so what the heck, right? Yeah, we got some good people, I mean it was amazing. The effort that people put into the songs like Mark Martin doing Let’s Get It On with those frogs… Yeah, I still laugh when I look at that.

Jim: Yeah, I remember the Grateful Dead when they were doing those, the Grateful Dead comics. Some of the art on some of that stuff was just fantastic. You did something on that too, didn’t you?

Fleener: Oh, yeah. They asked us what songs we wanted to do, and I go, “Oh, I’ve got to do St. Stephen.” Because St. Stephen, that’s like you know… I’m not a Deadhead, but I’ve seen them three times, and twice, I felt that magic. I was in the middle of that crap. Everybody had their shirts off, and they were all dancing around. And they were jamming, they were doing this sophisticated jam that was like something that like Coltrane would do. And I got caught up in that.

[00:30:00]

I did Chicken Skin right out, without even thinking about it. You know, talking about it. They were good. They were that good. But their records… I’m never impressed with their records. American Beauty is okay, but the records, they were quite…

Jim: That’s a good album.

Fleener: Yeah, they never quite captured…

Jim: I never liked Workingman’s Dead too, but yeah…

Fleener: Yeah, yeah. That one too.

Jim: I know what you mean.

Fleener: That was sort of like their American song book, those two. Almost every song on there’s like a classic. So anyway, when Kitchen Sink decided to do the Grateful Dead book, I was torn because it was work-for-hire, and I wasn’t really happy about that.

But I did know that Jerry Garcia was a Big Easy Comics fan and the rumor I’ve always heard is as soon as they made money, he bought all the back issues from collectors so he could have them. So, since it’s work for hire, that means they could use the art for anything they wanted in the future. But I figured, they probably wouldn’t use mine because it wasn’t realistic enough, like the Easy Comics, if you know what I’m saying.

So, when I did my version St. Stephen, I just tried to dredge up every graphic hit-me cliché I could think of, that so if they did use my stuff in the future, I wouldn’t feel too bad about it because I wasn’t giving away very good ideas. Just sort of good ideas, that I copied from some other hippy, right?

Anyway, we ended doing a blue line. It’s the only time I’ve ever colored a blue line, and it was horrible. I’m so glad there’s computer coloring now; that was really hard, that was really difficult. I hated it. But I liked the comics.

Alex: So, a couple of notes, you’d also alluded to it earlier, but the Crumb’s, and Mickey Rat’s Robert Armstrong we’re all so important to your start. Crumb sent you copies of Weirdo when he was the editor, and that was encouraging. Tell us about that interaction.

Fleener: Well it was so encouraging because after all the head shops were closed, and I think it was 1978 or ’79, you couldn’t find underground comics anymore. Then about… I don’t know… Somebody gave me a pile of Arcade, so I knew there were still people drawing… But just like, it was a mystery. How do they do these comics? I mean how do they get published? Who would even pay them?

It was just like this other universe. So, when Crumb sent me the first Weirdo I got, it was like fresh energy. It was wonderful to see a new crop of people, a new bunch of people, a new attitude. No more, “Hey man, I took acid last night for the hundredth time… Ha, ha, ha”. There were so many comics that did that. It got old… Or the guy having sex with a woman on acid, or it was just, you know… Everything was on acid.

And now, this was a different attitude, and it really appealed to me. And Bob Armstrong’s Couch Potato newsletter that was actually the first comic that I got paid for. I did this little strip called The Techno Cats, and I liked his Mickey Rat, I just think is the funniest comic book. That’s my top 10, Mickey Rat.

I actually got the idea for doing my cubist style from Bob, because there’s a strip on the back with the rat goes to a movie. And he goes to a porno movie, and on the stage, Bob drew the figures very cubistically. And then the punchline, of course, at the end is, “Uh, the book was better. Ha, ha.”

But I look at that drawing, and I go, “Gosh, you know what, people should draw comics…”, not like Picasso because I don’t like that guy… But I was thinking, this cubist kind of thing. Everybody does realistic, why not make it wild. I mean you can draw anything you want in comics. So, that kind of that lit my light bulb, and that’s when I started doing The Techno Cats, and making everything geometric.

Well, I was influenced by art deco too, and in ancient Egyptian art. Those are my things.

Alex: Yes. Right, and there’s almost like a 2D art with those hieroglyphics, right? And that they’re illustrating something in this 2D sort of way and then combining that with like a cubist, and now you have like this different kind of art form. Now that you mention it, yeah, I guess looking through your comics, like I can feel that. Yeah, that’s interesting.

Fleener: Oh god, when I went to the King Tut exhibit up in LA, I went three times. I know I was reincarnated from the ancient Egyptian times. The colors they used, the designs, it looked like stuff I did. I got kind of misty-eyed.

Alex: Yeah, you felt a connection.

Fleener: Really… And I love carnelian and I love turquoise [chuckle] so…

Alex: How fun… So then, Peter Bagge was the first to actually publish your stuff in Weirdo, and that started out in the letters’ columns, right?

Fleener: Yeah.

Alex: This was 1985, or so?

Fleener: Yep.

Alex: Yeah. What was he like as an editor?

Fleener: Well, if he liked it, he used it. If he doesn’t like it, he didn’t use it.

[chuckles]

In fact, he was interviewed by somebody, and he was talking about me because what I did was, I wanted to be in Weirdo but I thought it would be really ‘uncool’ to like send a letter like, “This is my submission. Oh, I hope you like it. Here’s my phone number.” So, I just started sending him art and he told this guy, he goes, “I didn’t know what she was doing… Was that a submission? Was she trying be friendly? I mean, I couldn’t figure it out… And then slowly she got better…”

[00:35:02]

And yeah, my first stuff stunk, and when he wouldn’t use it, I didn’t take it personal because I was just starting. And I always thought cartooning was like learning a musical instrument, you got a works for three to five years. I mean, you just have to. So, I did this little comic strip called All in a Day’s Work, and it was Godzilla blowing down a city and at the end of the day he has a cigarette or something. I forget exactly what it was.

And Pete goes, “I’d like to run this. And I go, “That’d be great!” So, I got a whole 10 bucks for that. [chuckle]

Alex: That’s good.

Fleener: Which is fine.

Alex: To start.

Fleener: I didn’t care.

Alex: Weirdo had three different periods under Robert Crumb, Bagge and Aline Crumb. Can you describe the difference in their styles?

Fleener: Yeah, I think it’s pretty obvious when Crumb was the editor, he was trying… he wanted to be the anti-Raw magazine. And so, he wanted to use outsider art and stuff like the frog by that outsider artist… Gahh , what’s the guy’s name?… Neil or something. You know, where the frog goes, “I’m going to cut you.” That one.

[chuckles]

And he’s using like Eleanor Norifice the crying elephant with the guitar, and all of this stuff, it was just ugly. But to me, I thought it was great. I mean I’m sick. I mean among all these people at the party, I like looking at slideshows. I like looking at people’s pictures of their vacation. And I really like the pictures that are out of focus, and look bad.

[chuckles]

Alex: There’s a dark undercurrent in those photos. Yes.

Fleener: Yeah. I mean it’s more interesting than something that’s perfect. So, Crumb’s Weirdo was outsider art, a lot of those photo funnies, which I thought were great. I love the photo funnies. Some people hate it, but I thought they were great. He had more of a, like I said, outsider art appeal.

Peter Bagge, he was going for the New York- Stop! Magazine, Punk Magazine guys Holmstrom, J.D. King, and the Wise Ass.

Alex: Yeah, Wise Ass, I mean, that definitely like it’s Bradley Comics. There’s a lot of Wise Ass in that. You’re right.

Fleener: Yeah, it was a kind of humor that Mad Magazine had that was very subtle. And he raised it up to serve more of a snot-nosed level which was fine. I thought a lot of it was mean-spirited, and I won’t tell you which ones, but I don’t think you should make fun of other artists. It’s okay to make fun of artist, like parodies are good, but to accuse people for just doing things for money… The satire was a little thin, on some of the stuff. Yeah.

Then when Aline took over, of course, she was publishing a lot of women, not just because they’re women. She was publishing the stuff she liked, they just happen to be women. So, I’d say, more autobiographical when Aline was doing… The materials are more autobiographical, that she published because we went on a cartoon vacation. Let’s see, we went to visit Bob Armstrong, Bob Crab and Kate Kane and then we ended up at the Crumb’s.

And I started telling the story about my mom, talking on the phone and explaining to her that I was editing Tits and Clits. And they started laughing, she goes, “Oh, you got to do a story. You got to do it. You got to do it.” And I go, “All right.” And so, that ended up in Weirdo… A mother and daughter chat.

Alex: Yes, yes. Okay, so then Aline, she had the emphasis on women, also autobiographical strips, right? So, like where the artist would like then talk more about their own life experiences. Because you started out with that, Madam X from Planet Sex, right? That was kind of like an earlier thing, wasn’t it? And then it kind of went into more autobiographical things, is that right?

Fleener: Well yeah, because it used to mean being a cartoonist, man, you had the build-up and the punchline, or it was a gag.

Alex: Yeah, like a daily gag, yeah.

Fleener: Or it’s a single panel, but it had to be kind of funny.

Alex: Yeah, cut to the punch, quick. Yeah.

Fleener: And I’m not really good at that. So, I’m lucky that this sort of more literary form of comics came along where you could write about serious stuff, and it didn’t have to be, “Ha, ha, ha, ha.” I was trying to be gag funny with Madame X, and meh… It didn’t quite work.

Alex: I liked it in that, there was a mix of like the 50’s Planet X concept with prostitution. Like that’s an interesting merge of two different things, so I liked it in that sense. But your autobiographical stuff is really compelling and the way you use the cubist stuff to illustrate like an intense emotion of that moment, it really describes it really well. It appeals to the way I think actually. And I think it’s good for dyslexics who read comic because they get what you’re getting at too.

Fleener: Yeah, I mean, how many times can you put “Boingg”… [laugh]

Alex: Right. Yeah, this is like a more interesting version of that, in a way. So then, do you have any particular favorite of yours from the stuff that you had in Weirdo?

Fleener: Oh, yeah. My favorite stuff was the voodoo Hoodoo stuff. And that’s what kind of got me… Like it took me a while to find out what I wanted to do and somebody, one day, said, “Well, have you read Zora Neale Hurston?”

[00:40:01]

And I go, “No. Who the hell is she?” Well, he was an old boyfriend of mine, and he knew I was into blues and jazz and stuff. He goes, “Oh god, you got to read some of the stuff. It’d be perfect for your artwork.” Good, I have nice friends, they’re always directing me to these places to go to.

And so, I took his advice, and I read her books and I went, “Oh, my god, this is comic gold.” Because I always wondered what the black cat bone was, and I always wondered what the mojo hand was, and here it was. So, that’s why my first comic was Hoodoo, there was this adapting her stories into comic form. And then after I read Dust Tracks on the Road, I go, “Yeah, I can write about my life… She was born in a little town, father’s a mayor, and she became a writer.” Well, that’s not very interesting in it it’s a summary. It’s kind of, eh, a lot of people do that. But it’s the way you tell the story, and I learned that from Zora.

And so, I like The Black Cat Bone, I think that’s my favorite one… Oh. Actually no, my favorite one in Weirdo was to Turn Off That Jungle Music.

Alex: Yeah, yeah. I read that. I actually looked through that one last night as well, yeah. That’s interesting because it shows almost like having racist family members but then growing up, and being almost like confused and turned off by that, and the cultural clashes that happen there.

Fleener: Well, because my grandmother lived on 42nd and Danchor off Martin Luther King Boulevard which was Santa Barbara Avenue, when I was a child. And she was the last white lady in that neighborhood, and she was like the Driving Miss Daisy gal because the guy across the street would take her to get her hair done every Thursday. And then she lived by herself, but my when my grandfather was alive… See he’s part Portuguese, so he was dark, and he worked down at Chinatown, and so he got along with everybody, because he was half Portuguese, so the neighbors loved him.

Fleener: And then she’d stayed there till she died in 1978. So, when I was a little kid it was pretty racially mixed, and then there was a white flight, and then the blacks moved in. Apparently, there was a black flight, and then the Hispanic people moved in, and now, the whole area has become gentrified. I looked it on Google Earth. I just about died. It’s all white people again. Oh, my god, well there used to be a Cadillac in every driveway, and now there’s a motor home. [chuckles]

So, anyway, I just grew up hearing the music next door. I go over there and I go, “Who’s that playing?” They’d go, “That’s Ray Charles. Why do you like that music, child?” I go, “I like it.” They’d go, “No, I don’t know if you should be listening to that.” My mom would go, “Get over here! Leave the neighbors alone.”

So, I was fascinated by the black neighbors because they cooked food all day, and everybody always seemed to be having a party. I know it sounds stereotypical, but that’s just the way it was… The ladies wore hats when they walk down the street. It was like a different world, because we were living in West Covina, and nothing’s whiter than West Covina, I’m here to tell you that.

I think it was really fortunate, in fact, when my grandmother died, I had to clean up her house, and she’d lived there since 1922, and she never threw anything away. So, I was out there loading my car, and these guys are coming down the street. They’re like totally, you can tell they’re high on something.

[chuckle]

And I see, they’re coming right towards me. The neighbors are opening the windows, they thought there’s going to be a problem. And this guy comes at me, it was a little kid that I used to play with, and he’s all grown up, and he’s so wasted. He goes, “Mary, what’s going on?” So, we had a nice reunion but we were from two different world at that point.

Alex: Right. Yes, that happens… As the tree branch grows, things differ. The fruit changes, in a way.

Fleener: Yeah, my mom was embarrassed to be from that neighborhood. She was a kind of a snob. And the people that live there were good people. The lady across the street took my brother and I to a Baptist Church event, one weekend, where they were speaking in tongues, and they had the band and the organ player. And we were the only two white kids in there, and it was fantastic. It was the most amazing thing I’d ever seen in my life.

Alex: Yeah, sure. Definitely more lively, and interesting, yeah.

Fleener: Yeah, but the point was, we were welcome.

Alex: Yeah, that’s cool. That is a good point. You’re right.

Now on another related subject, when did you start going to the San Diego Comic-Con? Is it like the early ‘80s, is that right? Like ’81, or when was that?

Fleener: 1986.

Alex: ’86.

Fleener: Yeah. I went with Dennis Worden. It cost $7.50 to get in. [chuckle] There was plenty of parking. We only had to park like two blocks away. And then they had this real long table where you had to fill out all these forms that took about the 15 minutes. In fact, I did a comic strip about it When Stickboy and Mary Go to the Comic-Con.

At first, I was like bored. I was like, “Oh god, it’s nothing but superheroes. But then we found Ron Turner’s table. And then we met Peter Bagge, and it was like, “Wow.” So, we stayed four hours and I couldn’t take it anymore, I said, “Dennis, I want to go home.” He goes, “Uh, you lightweight. Come on.”

And then the next year that’s when I met Dori Seda, and Kristine Critter and all the girls from San Francisco. Lux Interior was there with Ivy, and Mojo Nixon. I was like going, “Hey, this is pretty cool.”

[00:45:04]

Alex: Yeah, there’s a whole other universe at Comic-Con there. You’re right, that a lot of the superhero fanboys might not necessarily even know about.

Fleener: Well, they didn’t think much of us, because where Ron Turner was, he had his table and then there was Bob Crab and Kika, and Don Donahue, and Dori and there were three tables and that was it, of people that we could relate to. Then by the third year, we shared a table way in the back, and that was kind of fun. but I think it was only three years at 2nd and B, and then they moved to Harbor Drive.

Alex: Yeah, I would say the ‘90s, which Jim is going to take us into, but I would say the ‘90s they start celebrating more underground stuff at or independent stuff, I guess, at Comic-Con where that stuff becomes more inflamed and more of a presence. Definitely in the ‘90s for sure, it becomes almost like another under current mainstream, I would say. But… All right, Jim, go ahead.

Jim: Yeah, well let’s stay in the ‘80s just for a minute. Because, in ’85 and ‘86, I think for a lot of comic-book people, they think of it as, “Oh, that’s when Dark Knight and Watchmen came out.”

Fleener: Yeah. [chuckle]

Jim: Maybe they’ll add, “Oh yeah, and that mouse thing, Mouse came out, and that was it.” And then you just have everything else. It’s such a misunderstanding of that last half of that decade when you’re emerging, and so many people are doing such interesting work in such interesting publications. So, I kind of want to go through that to remind listeners that there’s a whole world out there as we’re saying, that isn’t Marvel, and that isn’t DC, and you were a big part of that. You and everybody you know were a big aspect of that. So, besides Weirdo, you had started working doing stuff for Wimmin’s Comix as well. Right?

Fleener: Yeah. Well, let’s back up a little bit because all of us knew we couldn’t work for DC and Marvel. We didn’t have those kinds of chops, and those guys could draw. I mean I didn’t like the books but I kind of changed my mind over the years. I was being you know smartass back then, Jack Kirby, I don’t like him… Well, you know what, I was wrong.

But two things happened minicomics and anthologies. And the anthology was a way for all of us to get published because nobody else would have us. And nobody had any ideas for superheroes and that’s all the big two wanted, this man or that man.

Then the minicomics, that was self-publishing, so everybody kind of met through that area. And yeah, the anthologies – that was Wimmin’s Comix; Tits and Clits, Rip Off Press, Buzzard, Centrifugal Bumble-Puppy… Oh, god, Prime Cuts, Fantagraphics, Snarf, even Critters, which was funny animals, and I know I’m leaving out a whole bunch of them but… Like even Drawn & Quarterly came, they had their first anthology magazine, Diamond wouldn’t carry it. They said it wasn’t good enough.

Same thing happened to Top Shelf too, and I told Brad, I said, “Just keep going. Don’t listen to these guys. Keep it up. Keep going. Keep going.” And so, we all had to scramble, but I don’t know, the anthologies didn’t sell very well, but they were at least a way to get published.

Now, Wimmin’s Comix was weird, because I’d heard about Wimmin’s Comix and I just sent a letter up to Last Gasp going, “What’s this Wimmin’s Comix? … Blah blah blah.” And three years passed, and I got a letter from Joyce Farmer because I think Wimmin’s Comix went through a period where it wasn’t printed because there was a lot of infighting, and nobody could get along, and all was crap. You’ve heard that story.

So, Joyce calls me, out of blue, and I said, “Okay, I’ll do Madam X for you.” She lived in Laguna Beach so I went to meet her. And then she told me about Tits & Clits which I had never seen before. She goes, “Well, I’m not going to do it anymore.” And I go, “Uh, come on, do one more issue. I’ll help you edit it. Come on. Come on.”

I was hungry, and so that’s how I met Joyce. We got involved in that, and we’re friends to this day too. So, to me, it wasn’t just me and colleagues, and getting published. I mean I met lifelong friends. We got a tribe. It’s really… We’re very fortunate. And like Wayno, look at Wayno, he’s a big hotshot now. [chuckle]… I love it.

Jim: I was looking at the Comics Journal cover that had all the different women; little pictures of all the women on it. I pulled that out. You’re there, obviously. Let’s talk about women emerging during this time. And yes, there’ve been women in comics before, I mean in Trina (Robbins) and all of that, but it does seem like with the opportunity to do these things in the ‘80s with the anthology books, it really takes off. And you have people like Julie Doucet, who I love, and later, people like Renée French, in just everyone, and all the ones that follow, in the autobiographical stuff. Can you talk about some of that as a movement, and how you guys were working together to some degree? I mean, you were connected?

Fleener: It’s funny because there is Wimmin’s Comix up in San Francisco, and Tits & Clits down in Laguna Beach. They were, at one point, didn’t know that there are two groups of people doing the exact same thing.

[00:50:03]

I thought the early Wimmin’s Comix had a little bit of forced feminism to them, it was a little preachy. It didn’t really speak to me whereas Tits & Clits really did speak to me because it’s like, “Women, we have to deal with consequences.” I mean, pretty heavy-duty consequences with sex. That that was something I could relate to.

The thing about Wimmin’s of San Francisco, you had to go to meetings. I guess they had all these meetings and everything. That, I thought, that was a little…

[chuckle]

I didn’t like that. Then Friends of Lulu came along, and it seemed like a bunch of women with a chip on their shoulder, and my attitudes, just go home and draw. Quit meetings and groups, and you got to do this, and then if… Screw that, go and draw. So, that issue of the Comics Journal that was #237, and I was the editor of that. I asked Kim Thompson if I could be the guest editor because I wanted to do a book about women but without the usual, “Oh so-and-so told me this, and this guy wouldn’t give me that job, and I was… blah blah blah.”

Now, I thought, “Goddammit, look at all these women doing comics. Let’s show them what’s there. I had 60 women do their self-portraits for the front and back cover. I copied Diane Noomin’s idea for Twisted Sisters.

Alex: Oh wow, yeah, I remember that.

Fleener: Yeah, and I wanted to have articles about… I reviewed comics. I was reviewing not just comics for girls but sex comics like some of the Eros Comix, and new people like Gabrielle Bell that nobody was paying attention to. I met her at Comic-Con, she had these little minicomics, and she’s so afraid, and shy. I just think by having those 60 women on the front and back that that makes a statement.

Jim: Oh, absolutely.

Fleener: It was 10 months of work, and boy, Gary Groth and Kim Thompson, they threw me to the deep end of the pool. They didn’t help me with anything. They didn’t assign me any writers. I had to do it all on my own. Ughh, that was a lot of work but time well spent.

Jim: Now, you didn’t do your own interview, or an interview, you did a two-page illustration for that, about girls at cons and girls of comics. But you didn’t choose to have you be one of the people that was talking about it, did you?

Fleener: No. Why? I don’t know. I think I ran out of energy [chuckle]. I was like just trying to get that damn thing done. The only thing I did was that two-pager with Trina and I were having coffee. And she had done a book about women cartoonists and I didn’t like it. She’s left out all these people, so she goes, “Well, do your own…” I wasn’t going to drop the F bomb but she said, “Do your own fucking book.” And I go like, ”All right. I’ll do my own F-ing book.” So, that’s why I did the Comics Journal, because of Trina’s challenge.

Jim: That’s what I was looking for I wanted to hear that. That’s interesting.

Fleener: Yeah. Trina and I didn’t become instant friends when we met up. And I did a strip in Weirdo making fun of her California Girls. She hated me for that.

Well, we all got invited up to North Hampton, to the cartoon art museum. It was Marie Severin, and Trina and I. And I think Marie could pick up that there’s a little tension. And so, we hung out for the whole weekend, and at the end of the weekend, it was like, “You’re not too bad.” And like Trina said, “Yeah, you’re okay.” And I consider her one of my closest friends, and we’ve spent the last two Comic Fest down here in Kearney Mesa, next to each other. We’ve had the best time. We had a lot in common.

She’s mellowed with age, of course, she’d still argue about the Zap Comix guys. She thinks they all like, idolize Charlie Manson. And I go like, “Oh, you’re so off base about that. They hated the hippies, especially, Spain (Rodriguez).” Then she goes, “Okay, I’ll agree with that. Spain, he was the one. He didn’t like Charlie Manson.” But she’s convinced that they all thought he was the greatest. I don’t know where that’s coming from.

Alex: That’s fascinating. Yeah, because she doesn’t even want to be called an underground artist because of how she feels about the artists from the Zap Comix.

Fleener: Well, she started writing, and as a researcher, and a person who writes documentary type style books, she’s very good. The book she wrote Last Girl Standing is her biography, and she got treated pretty badly. I mean I wouldn’t have put up with that crap.

Jim: But that’s a common story though, isn’t it? For women in comics? They’re going to run into that kind of mistreatment, more in those days, I hope, than today.

Fleener: Never. Not me.

Alex: But you know, because I remember because Jim asked Trina about that, have you had faced flak like that. But she said no. But you’re saying she did.

Fleener: Well, she’s talking about those parties where Roger Brand would take the guys in the other room and they’d talk about art, she’d go in there and then they’d all get up and leave.

Alex: That’s true. Yes, she did tell us about that. Yeah.

Fleener: I have never encountered one sexist anything in the comic business, ever. Maybe one time at the Comic-Con, I was reaching up to grab something, and one of the old guys said, “Hey, nice lay.” Well, that’s not something that affects my job or anything. That was just a kind of a caveman comment, which is fine, I don’t care. But no, the men have treated me… I’ve never had any problems. None. In fact, it was an advantage by that time I felt, it seemed, to be a woman.

Jim: That really opens it up for me to ask you about in this period, in the beginning the 80s through the mid-90s.

[00:55:04]

Who were the real heroes, in terms of the publishers, and maybe some of the artists, in terms of helping women get noticed and really emerge as a more of a force in comics than they were when Trina was breaking in?

Fleener: Oh, yeah. Ron Turner. I mean Ron Turner published, It Ain’t Me Babe. He published Wimmin’s. They published Tits & Clits. He published Dori Seda’s solo book. Now, Ron is terrific. I’m trying to think of someone else… Oh, that Cathy and Fred Todd from Rip Off Press. When they had their anthologies, they had a good balance of people. But once again they used the kind of art they liked.

I guess the closest to sexism I’ve had, people ask me, they wanted me to be in a book because they need a woman. But I wouldn’t call that sexism at all. But I don’t know, it just seemed like all of a sudden more women we’re doing comics and they had a chance to be published and thanks to people like the Todd’s, and Turner, and Denis Kitchen, of course…

Jim: I was waiting for you to say Denis Kitchen because he published Twisted Sisters, right?

Fleener: Yes, he did. And he’s a good cartoonist in his own right too. I think he’s got a book coming out.

Jim: Talk about Twisted Sisters.

Fleener: Well, a couple panels that I’d been with Diane, the one criticism was, where were the gay women cartoonists? Diane said, “Well, I only used work by women I liked, and I didn’t ask them who they slept with.” But a glaring omission was Alison Bechdel. And I didn’t know about her because she was only in The Advocate. Then when I discovered her, I think they’re like two years after Twisted Sisters, I was like, “Oh my god… Oh my god, Dykes to Watch Out For was fantastic. But I think even though Diane lived in San Francisco, The Advocates, where could you find them? They’d be in front of bars, or all the it bookstores, or things like that. I don’t think Diane was aware of her work.

Anyway, I just thought what she did was groundbreaking because the work was just so good, that it’s just such a variety of styles. Carole Moiseiwitsch, oh my god, I love her work. I guess she’s just decided comics aren’t for her, I don’t know what she’s doing now.

Jim: That’s a shame because some of that stuff, it was just amazing and nothing like it. I mean it looks like those early woodcuts from a long time ago, but with such power. I love her stuff.

Fleener: Yeah, yeah. the first time I saw her stuff was in Weirdo, and I think Denny Eichhorn wrote the story. I’m not sure… But anyway… Yeah, there’s another guy Denny Eichhorn, doing Real Stuff. Hell, he had more women in those issues than men, and he discovered people like Holly Tuttle, and Penny Van Horn… No, in fact, Penny was in Twisted Sisters. But yeah, Penny Van Horn with her scratchboard style. I mean, she just came out of Texas, it’s incredible.

Jim: Around in the late ‘80s, you were also doing stuff for some of the magazines like Hustler and Screw as well, right? Was that a money thing to pay bills?

Fleener: No! I love being in Hustler.

[chuckles]

I thought it was great. Because of my dad’s interest in Playboy, I used to read Playboy. And what I was interested in is the stuff that that Hugh Hefner published about our civil rights. He had a lot of articles about people being set up by the post office to have pornography mailed to their house, and they’re looking at 10 years in prison.

He was the first guy to publish Alex Haley’s book, Roots; chapters from his book. So, I felt Larry Flynt had every right to do Hustler. He took a bullet for it you know, and I voted for him when he ran for governor of California. Not just because I worked for Hustler because I don’t think there’s anything wrong with pin-up art, centerfold art. I don’t think there’s any wrong with these women, if they want to pose naked, do it while you got that body, honey. You can’t do it when you get older.

But the pay was fantastic. And my husband had been laid off from Teledyne Ryan, and they had laid off 200 people one day, and so I started getting work, 1500 bucks for a two-page spread, if you’ll pardon the expression, and it got us through.

I didn’t do anything for Screw, I think I had one little illustration in Screw, I don’t remember really. Then I think after about a year and a half, like guys like Kozak, and Pierce, and Cooper doing stuff for Hustler. and I apparently, according to Bill Nelson, who was the art editor, Larry started going, “Yeah, I don’t know. This art kind of looks weird in here… We should have more naked women…. Meh, I don’t know if I like it.”

So, that kind of, I don’t know if they still used underground artists in there or not, it’s not exactly the kind of magazine… I mean, I don’t mind buying the Playboy but asking the guy for a Hustler at 7/11 is a little…

[chuckle]

Fleener: I guess I could do it… [chuckle] Anyway, all my friends are buying Hustler are saying, “Oh yeah, we went to see your art Mary.” And I’m like going, “Yeah, right. Sure, you did. Sure, you did.”

Alex: It’s funny you mentioned about, like the dad having the nudie magazines.

[01:00:02]

And it being an influenced because I try to get patterns between artists. But yeah, Frank Thorne said that his dad had magazines like that. That was his, one of the formative things. So, that’s interesting that that was kind of formative for you as well, just that your dad was looking at that stuff.

Fleener: See what really happened to me is, I think was in the third grade, I was taking piano lessons. I didn’t like them very well and there was a little shack in the backyard. The lady said, “Go out there, and play.” So, I went out there, and there was like a hundred Playboys and I’ve never seen them before. And like I said, naked ladies, big deal.

But it was the cartooning. It was the beautiful artwork, like full pages of… I could tell, it was watercolor. But at that age, I was going, “What are all these jokes about bedrooms? I don’t get it. What’s with all the beds?” [chuckle]

But the art was just what blew me away. Every one of those cartoonists, they could do ink washes. You could just stare at them forever even though you didn’t get the gag. And my favorite one, of course, was Gahan Wilson, because I like monsters… I can’t believe anybody could say they looked at Playboy when they’re a kid and not say they were influenced by the comics and cartoons in there.

Alex: Yeah, yeah, I like that stuff. How do you feel about Gloria Steinem?

Fleener: I like her. I don’t know, she was a Playboy bunny at one time. I think that was kind of cool. I avoided a lot of that kind of reading about those political books and feminist books. I don’t think I’ve ever read one feminist book; I was more reading books like Black Like Me, and Autobiography of Malcolm X, and James Baldwin, and Zora Neale, that kind of stuff.

The feminist thing, I just think people should get paid equally. That’s where I stand.

Jim: So, let’s talk about the autobiographical stuff that was getting published, later in the Life of the Party train, and also in Slutburger. That became a major focus of your work at some point. Can you talk about what it was like putting that on paper like that? And how you did it? Why you did it? The influences and everything about that.

Fleener: Well, it’s something I’ve been doing a long time, is telling party stories. Like you go to a party, and… Let’s say you got pulled over by the cops and you got a ticket, you know he tore your car apart, and you he didn’t find your pot or something. You get to a party and have a few drinks, smoke a little weed, you start telling the story, you starting embellishing it. You kind of start making light of it. Kind of laughing with relief that you got away with it. You can really work a room with a story of something like that. And so, I’ve always liked to do that.

Jim: Was Howard Cruse an influence?

Fleener: Howard Cruse, oh my god, I have a pile of books here. I wasn’t sure we were going to be video or not, and on the very top is Stuck Rubber Baby. I think that book should be required reading for every teenager in North America.

Alex: Why don’t you show that cover really quick, since we have some video going. We might use some, we’ll see.

Fleener: Oh my god, yeah, here it is…

Fleener: Yeah, there you go. Nice. Stuck Rubber Baby.

Jim: My copy is six feet away. I could pull it out too. It’s great.

Fleener: Yeah, the page where the kid that gets lynched, he’s making them a casserole and they’re all in the kitchen about ready to eat, and Toland’s brother-in-law goes, “The Rhombus, ain’t that the gay bar?” [chuckle] and everybody goes like, “Uh… ” I own that page. And Howard was selling them for…

Jim: Do you really?

Fleener: Yeah.

Jim: Wow.

Fleener: I’m not sure what page number that is, but he was selling these pages for $200. And I was just like, “Oh my god”, and I wish I’d had some more money. I would have gotten five pages. But yeah… I never got to meet him either, unfortunately.

So, anyway, I got down to autobiographical stuff. I always had a rule that when I was doing stories about people, I would change their name and change their appearance. Because I don’t want get sued. So, that was kind of the little rule that I did. But after that, I just wanted to tell the truth about what happened.

Alex: So, like Burt Reynolds with a plunger up his butt. You’d change the face, maybe. Something like that.

Fleener: [chuckle] Yeah, I think I’d change the face on that one. I’d give him a beard. He’d have beard and blonde hair.

Alex: Oh, that’s good. Yeah, with maybe a cubist, during a certain moment of that.

Fleener: Yeah, that’s right. When he gets happy… Well I had to do that for Drawing Power, because the friend that betrays me at the end, is a little rich kid and he’s a prick. And had I used his name, and his real identity… Like obviously, in the story, the guitar player’s not the guitar player in real life, he was a different player. I don’t want to say anymore.

Jim: So, it’s not Kenny.

Fleener: Kenny’s name is not Kenny. I can’t talk about this, about who he really is. For two reasons, I hate his guts, and secondly, I don’t want to give him any legitimacy to who he is. And the guy who did dose me was a really creepy guy. I was hoping I can have one more page because that guy, even though after I moved here, he called me out of the blue and he starts stalking me over the phone. He’d say, “Remember that time when I raped you?” And all that stuff.

So finally, I found out he had a child, so I told him, “All right, next time you call me, I’m calling Child Protective Services, and then you can tell them why you’re so bored that you have to call me all the time.” And that was the end of that. That took care of that.

[01:05:02]

Alex: Wow, that’s crazy. That’s a horrible thing.

Fleener: Yeah. Well, he wanted to come down and see me, and I said, “Really? You want to come down to see me? Well I got a 38 Smith and Wesson I’d like to show you…

Jim: Oh, man!

Fleener: And I am a gun owner.

Jim: Wow… Yes, but you don’t like it, right? I mean I read where you bought the gun but you’re not loving having the gun, right?

Fleener: Well, I’m probably going to get rid of it. My mom is still alive, and she’s going to be 99 in January, and so all these things that I have belong to my father and they’re technically hers but when the time comes when she passes, I plan to sell everything.

Yeah, I did a story in Hotwire called The Judge and I was always anti-gun because they only serve one purpose. But when you have somebody trying to break into your house and try to break the window to your bedroom, it kind of changes your outlook on life a little bit. I had a knee-jerk reaction, and I had always wanted to shoot because I like archery, and I went to see if I could be a sharpshooter, and I was. They gave me the target to take home. [chuckle]

So, next time we go on vacation, I said to Paul (Therrio), “We should put the target in our window, so when people come up and they’re thinking about robbing our house, they might think twice. But no, it’s a horrible thing, and when you go to a shooting range, the smoke smells horrible, the noise… It was like, basically, you jump every time you hear it. It’s like a bowling alley. So, you’re standing in line with all these people with guns, I’m not going to do that again. I mean what’s to stop somebody from flipping out. Anyway, I had fun doing that experiment.

Jim: I want to go through some things that don’t get talked about in some of the interviews with you, and just throw some things out.

Fleener: Yehey. Okay.

Jim: I’m sort of all over the place… So, the AIDS Memorial Quilt you did a bit on that, right? Talk about that. I haven’t read anything about that.

Fleener: Well, thank you for bringing that up. I did the quilt for my friend Brent Scrivner, who actually grew up with my husband in Torrance. My husband was his family’s paperboy, and they went to the same high school. They went to North High and Brent was a genius. He made a robot in high school and he was the guy that designed the Devo flowerpot hats, and the freedom of choice wigs. He also did the PDK (PKE) meter in Ghostbusters, is that what it’s called? And he did props for Battle Beyond the Stars.

He started becoming really, really famous. He worked for Modern Props up in Venice. But he was gay, and he had to keep it a secret from Hollywood. And so, he died of AIDS. He was my best male friend, and after he died, they were going to throw out all the Devo hats he had in an apartment down in Torrance. So, I had to call it Mark Mothersbaugh and tell him, “You better run down to that dumpster and get those hats, or they’re going to go in a landfill.”

None of them knew that he was gay. They were totally shocked. And so, when the NAMES Project idea came up, I said, “Oh no, I have to be the one. I have to be the one.” I’ve got four yards of denim at home, because denim, right? Because the clothes, always wear denim and plaid shirts, and then I painted it with acrylic paint, and it took me about… Wait… It took about three months to paint that thing, because it’s 4 x 8 feet. That’s a big piece of fabric.

Then I was able to get pictures of him like on fabric because I want to put a picture of him on that on the piece. And these people in the local store they did that for me for free because it was a AIDS victim. And then when I got the panel done, I sent it to his mom and then they put all the sequins on it, all the little… So, everybody contributed in it… I think it’s the most beautiful piece of all the panels. And I also think that the NAMES Project is the most important piece of folk art of the 21st century. I don’t know if… Have you ever seen the whole thing laid out?

Jim: No.

Fleener: It’s powerful. You bring Kleenex. You bring a lot of Kleenex. Anyway, it made his mother and his father very happy. And now they’re coming out with the new Ghostbusters, and so his nephew wrote an article about Brent for some trade magazine, which makes me very happy. He should not be forgotten.

Jim: Can you send us a picture of that. That we could put on Comic Book Historians? Or maybe on the promotion of this? I’d love to have that seen, if it’s possible.

Fleener: Yeah, I have a picture. It’s not a very good one because it was taken in ’92, by his parents, and they didn’t have a digital camera. But you can see it well enough to see it. It’s kind of off-center, and it’s a little out of focus but I’d be happy to do that. Yeah.