Harvey Kurtzman: Between the Lines by Alex Grand

Read Alex Grand’s Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland Books in 2023 with Foreword by Jim Steranko with editorial reviews by comic book professionals, Jim Shooter, Tom Palmer, Tom DeFalco, Danny Fingeroth, Alex Segura, Carl Potts, Guy Dorian Sr. and more.

In the meantime enjoy the show:

The story of Harvey Kurtzman is one of innovation, wit, and sometimes, irony. Born to a canvas of wars, revolutions, and societal changes, Kurtzman created art that holds a mirror to the changing world around him.

![]() Kurtzman began in the mid-1940s with the Hey Look strip for Martin Goodman of Timely Comics, which metamorphosed into a one-tier strip called Silver Linings for the New York Herald Tribune Sunday. A photograph from 1949 reveals an optimistic Kurtzman alongside the likes of John Severin and René Goscinny, on the precipice of embarking on the EC Comics journey in 1950.

Kurtzman began in the mid-1940s with the Hey Look strip for Martin Goodman of Timely Comics, which metamorphosed into a one-tier strip called Silver Linings for the New York Herald Tribune Sunday. A photograph from 1949 reveals an optimistic Kurtzman alongside the likes of John Severin and René Goscinny, on the precipice of embarking on the EC Comics journey in 1950.

His work with EC brought forth “Two Fisted Tales,” noted for its intense scenes of war and harrowing depictions of the soldiers’ plight, such as in its 20th issue in 1951, co-created with Wally Wood. These raw portrayals, coupled with promises of “He-Man Adventure” juxtaposed the grim reality with a societal expectation of masculinity.

Kurtzman’s unique approach to his craft is evident in how he plotted out every page meticulously, as illustrated in the preliminary and final sketches for “Two Fisted Tales 26” from 1952.

Around the same time, Kurtzman took the reins of the “Flash Gordon Daily” strip, illustrated by Dan Barry. While Barry considered Kurtzman a genius, the two had a difference in artistic visions, leading to Kurtzman’s eventual departure and his heightened focus on Mad Comics/Magazine.

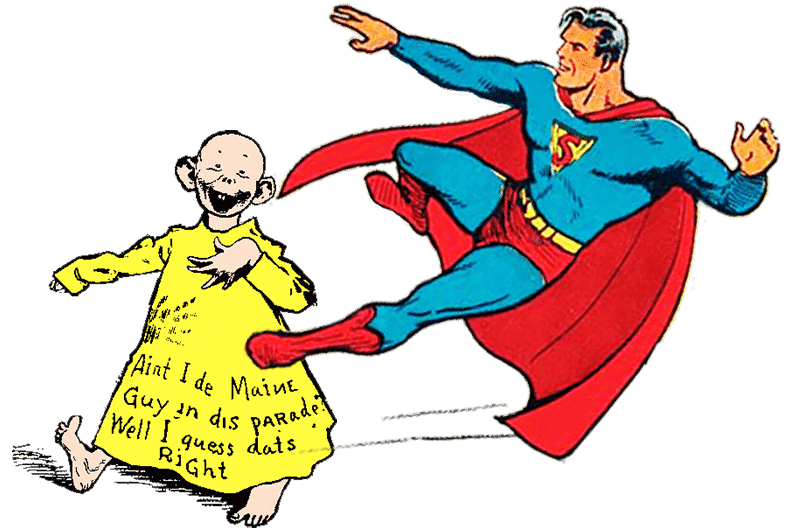

In 1952, MAD emerged under EC Comics and was an instant success, particularly with Kurtzman and Wood’s parody, “SuperDuperMan” in Mad’s 4th issue and the eventual depiction of Bat Boy and Rubin.

MAD’s success spurred a wave of imitations in 1953 from comic giants, making the 1950s a treasure trove of quirky, offbeat humor.

Unfortunately, in 1953, Kurtzman’s health took a hit when he contracted Hepatitis, leading to a reduction in his workload.

His sharp, satirical eye didn’t waver though, and by 1954, Mad took aim at the Kefauver Senate Subcommittee’s crackdown on comic books. By the time Mad converted to a magazine format to circumvent the Comics Code Authority, Kurtzman had made an indelible mark on its ethos.

However, things didn’t remain rosy. An ill-fated attempt to gain majority ownership of MAD led to Kurtzman’s exit between its 28th and 29th issues in 1956.

He then embarked on a new venture with the backing of the renowned Playboy magnate, Hugh Hefner. They launched “Trump” magazine in 1957, which, with its glossy finish and ambition to elevate the humor magazine genre, seemed poised for success. Bringing together a formidable team of talent including Wally Wood, Jack Davis, and Will Elder, the publication aimed to blend the biting wit and satire that Kurtzman was known for with the upscale presentation of Playboy.

However, a combination of factors, including possible financial strains at Playboy, disagreements over editorial control, and concerns about the magazine’s overhead, led to Trump’s premature demise after just two issues.

Heartbroken but undeterred, Kurtzman, alongside Jack Davis and other collaborators, pivoted to “Humbug” magazine in 1957, distributed by Charlton. Lasting for 11 issues through 1958, “Humbug” was a labor of love and communal effort, with Kurtzman spearheading the initiative. While Hugh Hefner had terminated “Trump,” he still extended goodwill to Kurtzman, offering the Humbug team office space either for free or at a negligible cost.

This gesture likely stemmed from a blend of personal fondness for Kurtzman and perhaps a touch of guilt for pulling him away from MAD. Hefner also featured Kurtzman in Playboy, December 1957 issue in “The Little World of Harvey Kurtzman” with 3 pages of text and 9 additional pages of Kurtzman gag samples which was good publicity for the writer-editor during his struggles.

This was one of the ways that Hugh Hefner showed deference and support to Kurtzman over the course of roughly three decades. Yet, despite the comedic genius packed into its pages and the clear dedication of its team, “Humbug” faced similar challenges as Trump, failing to capture the mass readership that MAD had enjoyed. The combination of market saturation with humor magazines, distribution challenges, and the shadow of MAD’s monumental success made it an uphill battle for “Humbug” from the outset.

In 1959, still determined to find a platform for his distinct brand of humor and storytelling, Harvey Kurtzman released “Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book.” Published by Ballantine Books, this work is of notable significance in the history of American comics for being one of the first original graphic novels.

It comprised four long-form satirical stories. Unlike the adventure tales suggested by the title, these stories delved into the complexities of mid-century American culture, each set in a different environment, yet all maintaining Kurtzman’s hallmark wit and incisive critique. One of the standout tales, “Thelonious Violence, King of the Jungle Bunnies,” was a satirical take on popular detective stories of the time, highlighting and subverting racial and cultural stereotypes. Another story, “Compulsion on the Range,” lampooned the then-popular Western genre. The stories, while humor-filled, were also deeply personal reflections of Kurtzman’s observations of and experiences within the media industries he had worked in. His distinctive art style, which combined detailed backgrounds with exaggerated and expressive characters, was on full display in this book.

Unfortunately, despite its groundbreaking nature and the artistry contained within, “Jungle Book” did not achieve significant commercial success. Its print run was limited, and the graphic novel format was not as recognized or as widespread as it is today. However, over time, it gained a reputation as a cult classic, and today it’s regarded as a pioneering work in the graphic novel genre, showcasing both Kurtzman’s versatility as a storyteller and his prescience in realizing the potential of longer-form comic storytelling.

In 1962, “The Executive’s Comic Book” was released by MacFadden Publishing, spotlighting Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder’s “Goodman Beaver” adventures, originally featured in “Help!” magazine. To accommodate the vertical layout of the book, Elder enhanced the artwork, fleshing out the pages with additional illustrations. However, the duo faced legal turmoil when Archie Comics took issue with their character parodies. In the ensuing legal battle, Archie Comics not only criticized the satirical portrayal but also successfully gained ownership of the entire book. This incident underscores the fine line that satirists like Kurtzman and Elder tread in their quests to humorously critique popular culture.

As the 1960s rolled in, counter-cultural comics, like the iconic Zap Comix, surfaced.

Kurtzman’s Help! magazine became a forerunner in this movement, showcasing the talents of newcomers like Robert Crumb, and providing a launchpad for the likes of Gloria Steinem and Terry Gilliam.

Despite professional setbacks, Kurtzman continued to produce masterpieces through the 1970s and 1980s, notably “Little Annie Fanny” for Playboy, a combination of slapstick and sensuality.

“Little Annie Fanny,” a collaboration between Harvey Kurtzman, Will Elder, and Russ Heath, was a satirical gem in “Playboy” magazine.

In 1978, they humorously spoofed “Star Wars,” drawing parallels with “The Wizard of Oz” through characters like the Tin Man, and wove in contemporary references like Lee Majors’ “Six Million Dollar Man.”

The art evolved from Classic to Modern/Pop Art between 1963-1967, celebrating styles from 1930s strips like “Popeye” and “The Phantom.”

![]() Their visuals strikingly merged Jack Davis’s illustrative humor with Frank Frazetta’s sensuality, encapsulating elements like 1960s surfer vibes.

Their visuals strikingly merged Jack Davis’s illustrative humor with Frank Frazetta’s sensuality, encapsulating elements like 1960s surfer vibes.

![]() The strip, mildly parodying “Little Orphan Annie,” also contained nods to various personalities, including Hugh Hefner, and featured recurring background details, known as Elder’s “chickenfat.” His propensity toward depicting women also found further expression in “Betsy’s Buddies,” a fresh take on modern urban sexuality that he cocreated with Sarah Downs.

The strip, mildly parodying “Little Orphan Annie,” also contained nods to various personalities, including Hugh Hefner, and featured recurring background details, known as Elder’s “chickenfat.” His propensity toward depicting women also found further expression in “Betsy’s Buddies,” a fresh take on modern urban sexuality that he cocreated with Sarah Downs.

The early 1980s also came with a professional recognition of his talent with the comics medium, where he taught a master class in the subject.

However, the late 1980s brought health challenges, with the added sting of acknowledging that he didn’t own the rights to “Little Annie Fanny.” Yet, Kurtzman’s spirit remained unbroken, reconciling with Bill Gaines and co-writing the book, “From Aargh! to Zap! Harvey Kurtzman’s Visual History of the Comics” in 1991.

Harvey Kurtzman’s journey through the world of comics was never a straight path. It was filled with twists, turns, successes, and setbacks. But throughout it all, his indomitable spirit and unparalleled creativity left an indelible mark on the world of comic art. In his later years, Kurtzman battled Parkinson’s and colon cancer. Ultimately, in 1993, he succumbed to liver cancer. As the world bid him farewell, it became abundantly clear that Harvey Kurtzman’s legacy would continue to inspire generations to come.

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out our CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.

Images used ©Their Respective Copyright Holders