Dave Gibbons Biographical Interview by Alex Grand & Mike Alderman

Alex: Well, welcome back to the Comic Book Historians Podcast. I’m Alex Grant. Go to click on the Subscribe and Follow buttons. I’m here joined with my co-host Mr. Mike Alderman of Patriot Comics. Mike, how you doing?

Alderman: Doing well, Alex. How are you?

Alex: Well, I’m good. The audience doesn’t know, but the Jim Steranko interview that we did or that I did some years ago, actually Mike was there in the room. We were there with him for those four or five hours, from 1:00 am to 5:00 am, having fun, and doing it. Mike also was kind enough to connect me and my friend, Bill Field for the Neal Adamszine we did with his son, Jason Adams.

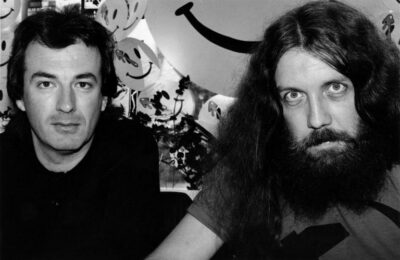

So, Mike has been a friend of the Comic Book Historians Group for a long time, and he brings his good friend, David Gibbons, co-creator of Watchmen, artist, inker, writer, letterer, and building surveyor.

David Gibbons, thank you for joining us today.

Gibbons: Very welcome. It’s a pleasure to be here. Nice to see you again Mike, and nice to meet you Alex.

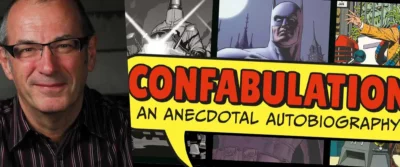

Alex: First, I want to say, I loved your book, okay. I read it. I read the whole thing.

Gibbons: Oh, good, good. You’ve read every word.

Alex: Yeah. I’ve read every word. I’ve done all my research, although there’s all that info at the end like a catalog.

Gibbons: Yeah, yeah.

Alex: I didn’t read the catalog part at the end.

Gibbons: Okay. We’ll let you off. We’ll let you off there.

Alderman: [chuckle]

Alex: But I read the narrative and I loved it. It really brought your perspective, your emotional, psychological perspective on your career in these interesting anecdotal pieces from A to Z which I loved. So, I just want to say that before I get started.

Gibbons: Good. Thank you. Thank you.

Alex: So first, how did your childhood experiences, early comic book reading, shape your desire to become an artist? I know that Superman’s your favorite. You’re more of a DC Comics than a Marvel guy, tell us about your childhood experiences and your early comic readings.

Gibbons: Well, I guess from the very beginning, American comics made a huge impact on me because back in those days a lot of the British comics were kind of tabloid format, and anthology comics, and were in black and white, printed on horrible paper.

And then, you started to see American comics. Initially, Australian reprints of American comics, but they were in full color, and they were much more exciting, and they had complete stories in them. There was just something really, in postwar Britain, that was kind of gray, and a bit depressed, and there was still food rationing.

There was something about this glimpse of American civilization that was absolutely kind of romantic, I guess, as much as anything. It’s bit like the fabled Gardens of Babylon or some impossibly kind of wonderful thing that was off there in the distance somewhere. Not only did you obviously get the comic strips with Superman and Batman, mainly to begin with, but you got print ads for like Tootsie Rolls or Schwinn Bicycles or Daisy BB guns, none of which we had over here, and all of which looked absolutely wonderful.

I also got to go on on vacation one year, to a place on the coast of Norfolk, which was the site of a lot of American Air Force bases during World War II. In this row of houses that we were staying in one of, the rest of the people there were Americans. They were USAF guys with their families, and I got to be friendly with some of these American kids.

Interestingly, they weren’t particularly fond of comics. They had a few comics but they were things like Archie or funny animal comics. But of course, they had all the toys, and they had all the clothes, all the really cool blue jeans, and check shirts, and all that kind of stuff that you didn’t see in England. We went back there a couple of times, and that sort of cemented my love of things American.

I’d always like to draw, my dad who was in the field of town planning and architecture. He would be drawing plans in the house, to make extra money, in the evenings. So, there was always a drawing board and there was always professional inks, and pens, and pencils, and rulers, and triangles, and things.

So, all that material was there, and I started to make up my own comics with my own sort of kind of knocked off versions of Superman and Batman. Superman was Atom Man, and Batman was Birdman just so you know, you wouldn’t suspect anything.

Alex: And you also had a what, a team Freedom Fighters as well, right?

Gibbons: Yeah. I mean I just love the Justice League. In fact, that house ad I’m sure that you can recall it. When I first saw “The Justice League of America, just imagine the greatest comic book heroes of our time have banded together as the Justice League of America”.

Well, annoyingly because of the way that comics were erratically distributed, I didn’t get to see a real Justice League comic for ages. But I kind of created my own surrogate one, trying to imagine what it would be like if all my characters all got together in one big story.

So yeah, it was just from the beginning, it was tremendously exciting. I had an older cousin as well who loved comics, and he gave me a lot of his comic book collection. So, I was kind of swimming in comics. My granddad worked in a store that sold comics, so he would send me a comic every so often. It was a thing that was always there in the background.

And I had this kind of childish idea that at some point, I might be able to draw American comics. But it seems so far off, and that world seems so far away that I only kind of half-believed it would ever happen. But miraculously, it did.

Alderman: Can you narrate the challenges and breakthroughs of being a self-taught artist in your formative years?

Gibbons: I guess, one of the problems with copying is you learn all the surface tricks, you learn all the ways to hatch things, and all the little cute ways of drawing noses or making things look like you know what you’re drawing. But sometimes, that’s really just repeating patterns.

Actually, I kind of made the breakthrough when I studied anatomy, after I decided that yes, I did want to try and be a comic book artist. I studied lots of anatomy books and that made a huge difference to the quality of my figure drawing. I also got to go to some live drawing classes which again made you concentrate on what people really look like, and think about weight, and stuff like that.

So, it’s kind of, it’s an incomplete education. Looking back on it, I sort of wished I’d gone to art school and I’d maybe experimented with things other than just drawing in pen and ink, like painting, and charcoal, and stuff like that.

But I kind of suspect that if I had gone to art school, I might have rather wasted my time, whereas because I couldn’t go to art school, there was no viable path by which I could get to art school, because the school that I went to was a very academic school that it kind of gave me something to push against. And I suspect that having to try and make it on my own and prove that I could do it, actually gave me more of a spur than it just been handed to me on a plate.

Interestingly enough, certainly in England, of people who draw comic books, it’s roughly 50-50 between those who went to art school and those who didn’t. So, I think, again, what it comes down to in the end is perseverance, and motivation, and that was the thing that I did have. That was the thing that powered me through when my drawings weren’t so good or when I got knockbacks, and “thanks but no thanks”.

Alex: I noticed, reading your book, that you have a rebellious streak in you from watching comics being burned, and the anger at that, and kind of you’re working underground stuff, that you have a rebellious streak. So, maybe there was some rebelling against the system as you did it on your own, which I think is amazing.

I know that you were working, essentially, as a building surveyor. I want to kind of preempt this with that you were actually reading comics in the `60s. Although a lot of people see you as a late Bronze Age kind of pre-modern age comic artist and writer, you’re actually born in 1949. You had a whole life in the `70s in the British comic scene before entering America.

So, what was that defining moment from building surveyor to professionally doing comics? And I say that more in the lens of not reading comics for a few years…

Gibbons: Yeah.

Alex: And then reading the fanzines, Fantasy Advertiser, and getting hooked up with your friend Dez Skinn. What was that transition about?

Gibbons: Well, first of all, I would like to say that I’ve never really thought of myself as rebellious. It’s just, if what I want to do conflicts with what other people want me to do, that’s when the kind of act of rebellion comes in. I’ve never been one of life’s rebels. I’m much more after a quiet life than a hugely disruptive life. And I’m quite happy to let other people do their own thing, and believe what they want to believe, and do what they want to do, as long as they don’t involve me in it. So, it’s rather a passive form of rebellion if you like.

I mean, I can remember there were two things – I read comics when I was a kid growing up and then when I got to my mid to late teens, like a lot of people, I sort of fell away from it. There were other things I was interested in, you know, drinking, and girls, and all that kind of stuff.

And I hadn’t looked at a comic for a long time, but I was out doing my surveying training, and I went to buy a pack of cigarettes…

I used to smoke in those days. I don’t anymore. Please don’t smoke if you’re watching this. It’s a complete waste of your health and money so don’t do it. Just beause Dave Gibbons did it once, doesn’t mean you have to do it…

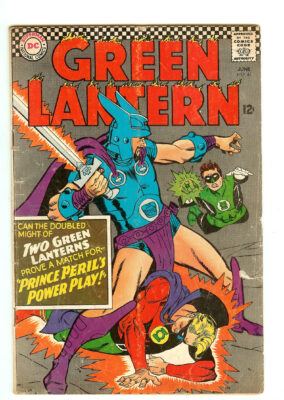

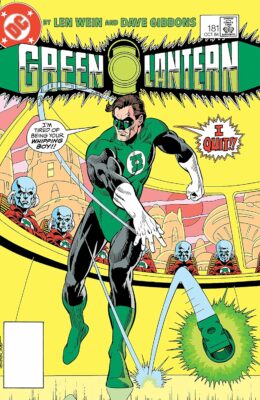

I was in this store standing in a line to get my cigarettes, and I was right next to a spinner rack, and I thought, “I haven’t looked at a comic spinner rack for a long time.” And front and center was a Green Lantern comic. I think it was Green Lantern #50, and it was called Prince Peril’s Power Play. It was a beautiful Gil Kane cover, much more dynamic than anything I’d seen Gil Kane draw when I was a kid.

I think it was the Golden Age Green Lantern lying on the floor with this barbarian with an armor and a big sword standing over him and Hal Jordan kind of flying in from the background. I thought, “Wow! That looks great!” So, I thought I’m going to buy it.

I actually I was so craven that I made some kind of excuse about… “I’ll have some cigarettes, and I’ll have this comic book. Uh, it’s from my younger brother.” I wasn’t admitting that at my age of 18 or whatever it was, I was still reading comics.

And I thought. “Wow! Comics have got so good in the time that I’ve been away from them. They’ve been so good!”

Then, I had to go to work as a surveyor, and that involved me going all over various parts of London, and there was one particular area that was a bit of an impoverished area called the Old Kent Road. If you’ve ever been to London it’s quite a famous address, the Old Kent Road.

They had lots of secondhand bookstores there, and I used to go in those, and buy up the comics that I’d missed from the time when I wasn’t following American comics in between me giving them up and me discovering Gil Kane, and you could buy them cheap.

But I remember one day, picking up a copy of Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. and I flipped through it because it wasn’t a title that I bought every issue. I flipped through and I thought, “My God! This artwork’s dreadful! I’m absolutely amazed that they printed it. It’s so poor.” And then I leafed on it a bit further I read Stan’s Soapbox, and it was a blurb by Stan about this issue of Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. drawn by young Britisher Barry Smith.

A little light went on. It was like, “Young Britisher. I’m young. I’m a Britisher. There must be a way to do it.” It’s not… It’s impossible or it’s not that only people with Italian sounding names who live in New York City get to draw comic books. I though, “There must be a way to do it.”

And then, the plan quickly formed. If I redraw it, and I do it better than this Barry Smith, then they’ve employed him, they’ve got to employ me because obviously, I can do it better than he can. So, I discovered by this time that comics were drawn on big sheets of Bristol board. So, I brought some Bristol board and I redrew the whole thing. I didn’t look at particularly what Barry Smith had done but copied the script, and redrew the whole thing.

I have to say, at the end of the day, it was probably worse than what Barry Smith had done with it, but at least it gave me… There is a possibility. Somewhere there is a door you could walk through.

So, it was at that point that I started seeking out fanzines, because I’ve been in fandom when I was much younger, and I reestablish some contacts there. I got to know Dez Skinn, who worked just around the corner from where I worked as a surveyor in London. And I took my samples around to him and he got me some work in his fanzine.

I don’t think I was quite ready for the professional comics, but I started doing stuff in his fanzine, and I met lots of other people of a similar age to me who were comics fans. That was how the whole ball really got rolling.

Alderman: Dave, how did working with Agent Barry Coker facilitate your transition into Marvel UK and later DC Comics?

Gibbons: Well, it’s hard to believe these days when there aren’t so many comics about, certainly in the UK, but comics used to be such a popular thing in Britain that they had to get in artists from abroad, from particularly Spain, and Italy, and South America, to draw the comics. And because obviously, there was a language barrier and a distance barrier, there were several maybe a dozen art agents in London who specialized just in comics.

One of these was Barry Coker who became my agent. He’d seen some of my stuff in a fanzine and thought that he could get work for me. He was a really nice guy… I haven’t seen him for a year or so but I’m still friends with him. He treated me so fairly. As I got more and more better known, he actually reduced the commission that he took, which is a really unusual thing for an agent to do, no matter what field they’re in.

He got me work for another British comics publisher called DC Thomson, no relation to DC Comics at all. They were up in Scotland, which is quite away from where I lived down in the south of England near London. But he had a really good relationship with them, and he got me regular work doing stuff with them, which was really… There was the self taught, bit of my talent, but this was really kind of Hands-on Comics 101, because although their comics were pretty traditional and not particularly exciting visually, it was all about telling the story.

So, I would send a penciled episode of maybe three or four pages and they would then send it back the following week with notes written on it, with Post-It notes saying, “We need to see the action here more clearly” or “We need to see the reaction on this character’s face” or you know, real nuts and bolts of how you should do comics.

They also used to inventory stuff before they published it, so there were no rush deadlines. They’d give you as long as you need it. They didn’t pay you very well, but it was still being paid to learn on the job, from people who really knew what they were doing.

So, by the time things like 2000 AD came along I’m working for, eventually for DC Comics in the States, I really kind of knew what I was doing. I knew I’d had a real good insider’s education on how to tell stories in pictures. And I would never have had that if it hadn’t been for Barry Coker.

Alex: In the midst of the Fantasy Advertiser, and the Barry Coker, and the early British art comics you were doing, I read that you had also been doing like underground comics. How does that fit in timewise? What were you doing with that?

Gibbons: My sister had been going to the local university, I suppose you would call it. She brought home a leaflet one day from somebody who was publishing a magazine for young people. They wanted artists, and comic strips, and jokes, and stuff like that, and I thought, “Ah, this could be a chance to get in print.”

So, I wrote them quite a pompous letter saying, “I’m Dave Gibbons. I’m a young comic book artist and I’m a proper comic book artist. I’m not one of those who treats it as a pop art fad. I’m trying to remain faithful to the legacy of the great comics of the pop art.” You know, it was really quite sort of a pompus thing.

Anyway, I met up with the guy who’s doing that, and I agreed that I would do a two-page comic strip for him, and I did a thing called Litterbug, which is reprinted in my autobiography. It’s a two-page thing about, funny enough, about damage to the environment, which is quite pressing because that’s obviously such an overriding concern today, and that saw print.

And then, Dez reprinted it in one of the magazines he was doing, and it was seen in there by a guy called Mick Farren who was in on the British underground scene. He was a musician and he was the editor of a kind of hippie mag called International Times. He reprinted it as well. He was surprised because he thought, by the art style, that I was an American underground artist rather than being a homegrown Brit. So he published it.

Then ,it was seen by a guy called Felix Dennis who was one of the people behind the magazine called Oz which famously got sued for obscenity in the sort of late ’70s, early `70s, probably, and he was looking for comic book work.

Really at that point, what I was interested in was getting my stuff in print. And again, he didn’t pay very much money but we did some quite interesting strips, and he let me completely create some myself, write and draw them both. Although my stuff was never particularly sex, and drugs, and rock and roll, it kind of fitted a little bit that underground ethos. The rather more refined end of the underground ethos, I think.

I worked with him for a while. He later went on to publish consumer magazines, and became a very, very rich man, and had a fantastic estate somewhere in England where he lived with his wine collection, and several women at the same time. So, he kind of…

But it was weird because he was spurred on because he’d been part of this magazine called Oz which was done, which was prosecuted for obscenity. The judge, when he sentenced him, at the end of his speech said, “Felix Dennis is by far the least intelligent of these three people, so therefore I will not punish him as severely.” And then in the end, they on appeal, it was all crushed anyway.

But I can imagine Felix, having a judge say, “You’re not as intelligent as these other people.” would be the perfect spur to say, “Well, I’ll show you.” and he did. He lived a very good life, a very successful life. And quite an artistic life as well. It wasn’t all just about the money with Felix. He died a few years ago.

So, that was a kind of underground connection there. It was all just part of me trying to desperately get into print and get my work seen.

Alderman: Dave, how did working on horror and action titles influence your approach to storytelling and character development? And can you share a memorable story or challenge from creating the Year of the Shark Men for DC Thomson’s Wizard Magazine?

Gibbons: I mean that was really quite early days, and what DC Thomson used to do, because they were like a family business, they were not very artist or writer friendly. You can forget anything about being given any rights or reprint money or anything like that. They were really not very generous.

What they used to do was recycle stuff, so before they became comic papers, in other words with drawn continuity, they were text papers. They were like the old pulp magazines where it’s page after page of type. What they did was adapt a lot of those type stories, prose stories, into comic books, into comic strips. So therefore, they weren’t actually great comics because they were much too wordy, and things happened much too slowly, and everything was overexplained.

The Shark Men was one of those. But it kind of fitted with what I could do, because they were kind of these undersea aliens with futuristic craft, and skin tight costumes, and strange weapons, and everything like that. I can’t remember that there’s any particular anecdote that applies to that really other than, again, it was an early thing that I got to do for DC Thomson.

I think it helped get me work later on when obviously people at Fleetway who published 2000 AD saw it, and saw that I could handle science fiction stuff. So, I think that’s what I’ve got to say about that really.

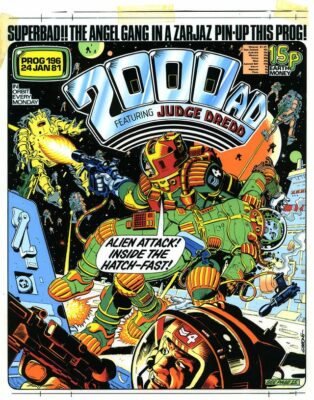

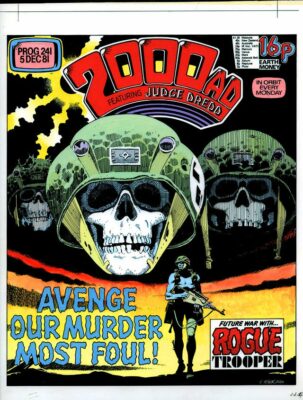

Alex: You were a key contributor to 2000 AD, from its first issue. You mentioned 2000 AD just now. First, how did that get started? I think you hinted to it already, but then, how did your work on this title, including the creation of memorable stories and characters influence your career and art style?

Gibbons: 2000 AD, for so many of us – myself, Brian Bolland, Kevin O’Neill, Mick McMahon came just at the right time, because we’d all been working for a while. So, we were no longer amateurs. We were professionals although not particularly professionals in high demand but we’ve sort of learned how to do it, and learn how to be professional, and deliver stuff on time, and all, and be pleasant people to deal with, which is half the battle really I think to get freelance work. To be reliable and to be a nice guy, basically.

But I can remember what happened was… Another thing, I might mentioned this quite early to see print, was an album cover that I did for the English band Jethro Tull, who I’ve never been a huge fan of, but it was a job of work anyway. It being not for comics and being for the wider world of of art, I got paid a pretty good fee for it despite my inexperience.

A friend of mine who works on the local newspaper heard that I’d done this album cover and I got really well paid for it. He said, “Oh, we’ll run a piece on you in the local paper.” So, they interviewed me, and took pictures of me at my drawing board.

I didn’t divulge to them how much money I’d got paid because my dad always told me it was a really bad idea to discuss how much money you earned with people because they either think you’re a fool for not earning enough or they think that you’re just being lucky when you get paid a lot. So, I didn’t divulge publicly even in the local newspaper how much I got paid.

It was £300 actually, which was a hell of a lot of money back then.

Anyway, through that, unbeknown to me, only a little way away from where I lived… I still lived with my parents at that time… Was another guy Mick McMahon, who was an aspiring comic book artist. He wrote a letter to me having seen this piece in the local newspaper. He came to see me because I was only a little bit older than him. But I was like the seasoned professional and he was the young apprentice wanting to break in.

We got on really well together and I was really impressed with his work. I was going up to London one day on the train to deliver some artwork, and I bumped into him on this railroad on the railway station. He had a pile of artwork under his arm. I said, “Oh, what’s that Mick?” And he said, “Oh, it’s this new comic they’re doing at Fleetway. It’s called 2000 AD. It’s a science fiction comic.”

I said, “Wow! That’s just the sort of thing I’d like to be on.” because we obviously shared the love of science fiction. Then, that same day, I went to see my agent, I said, “Barry, they’re starting this new comic over at Fleetway”, which wouldn’t have been common knowledge. They tended to keep these things quite secret. “I’d really like to get some work on it if I could.” He said, “Okay.”

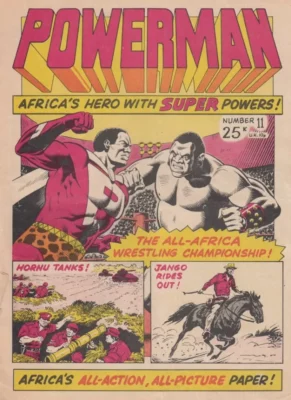

And we got straight on a bus and went across the bridge over the Thames, and went to where 2000 AD was being published, and was introduced to the editor, who was a guy called Pat Mills, who I’ve known for ages and who I recently kind of collaborated with again, but that’s another story. They saw the things that I’d done for DC Thomson and they also saw a comic book that I’d done from Nigeria in collusion with Brian Bolland which was called Powerman, who was essentially a black Superman.

These comics were published in Nigeria… Our first question was, how come you can’t get Nigerian artists? And they said, “Well, there is no heritage. There isn’t such a thing in Nigeria. We just reprint English comics, and of course, they’re full of of white, you know, Air Force pilots or white sportsman. We think it could really be a hit and then hopefully people in the country will be inspired to create their own comics.” Which did eventually happen after many, many years.

So, I’d shown them, at 2000 AD, Powerman so they could see that I could draw people specifically, as if it makes any difference, black people flying through the air, because they had a sports strip called the Harlem Heroes which was kind of a futuristic version of the Harlem Globe Trotters a basketball team.

So, it was these guys who looked like the Globe Trotter who would fly around with jetpacks throwing these metal balls into these suspended goals and everything.

I had a lot of fun doing it. No other artist that they tested for it, quite got it right. They were European artists and they made everything look too realistic, whereas I did it with superhero clothing with no wrinkles, and no folds, and everything fitted perfectly, and looked super cool. So, that was how I started working for 2000 AD. And then, after a year or two more maybe working for them, that led up to being recruited by DC Comics.

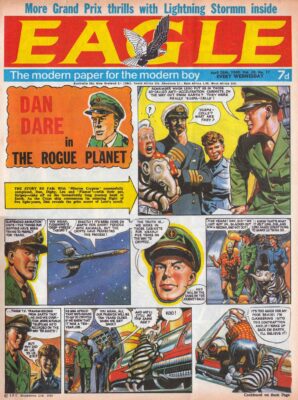

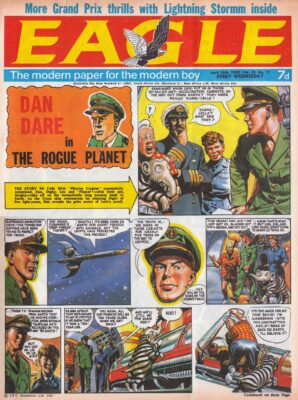

Alderman: What personal and professional significance to working on Dan Dare hold for you?

Gibbons: When I was growing up, I’ve already said that American comics and American culture next to what was going on in England looked very appealing, and very bright, and was in full color. Amongst British comics, there was one standout comic which was called the Eagle. It was lithographic printing which is really high quality printing in full color. Not every page was full color but the front and back, inside covers, center spread, were all in glorious painted full color.

And I absolutely loved that, and the real selling point of it was the star of the front page of it called Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future. If you or your viewers haven’t seen it, you should seek out some Dan Dare because it’s absolute worldclass stuff. It’s easily the equal of Alex Raymond or Hal Foster or any of the French, and German, or Spanish artists. A guy called Frank Hampson, but unfortunately, the business side of it meant…

Although he did really well financially out of it for a while, he eventually got shafted and didn’t actually enjoy personally the success which the sales and everything of Dan Dare should have given him. And he actually became a bit embittered, and he left the whole world of publishing, and started working as a graphics technician at a local college.

But anyway, I love Dan Dare and Dan Dare had featured in the first issue of 2000 AD. Not drawn by me, drawn by an Italian artist called Massimo Bellardinelli. He’d given it rather a sort of hallucinatory quality and they wanted a more down to earth, almost military kind of feeling to it. That there was Dan Dare who was like a colonel and his team of soldiers behind him. Kind of doing a Star Trek thing, flying around the universe.

It was also at the time that there were rumors going around about Star Wars. So, that was obviously seen as a pointer to the way things could go.

So, they offered me the chance to draw it, and I have to admit that even being aware of what had been done to Frank Hampson, I’ve often thought the noble thing to do would have said, “I’m not collaborating in this terrible treatment of a fellow professional.” I, of course, being young and needing the money went, “Oh yeah, that’s great.”

So, I ended up drawing Dan Dare for several years and I quite enjoyed it. I had a few goes at doing it. We never could get it quite right because it was never going to be what the thing in the `50s was, which was full color on really good paper which was Frank Hampson and another five or six artists all producing just two pages a week. So, the work, it was a bit like Little Annie Fanny. Not in its content, but the sort of finish, and the attention to detail, and the intense perfection of it.

I was actually introduced to Frank Hampson, Dan Dare’s creator, by a mutual friend who quite mischievously said, “Oh hello, Frank. This is Dave Gibbons.” He said with a sneer, “This is Dave Gibbons. He’s drawing Dan Dare for 2000 AD.” So, I held my hand out and said, “I’m really sorry that I can’t do your work justice, Frank. It’s been a huge influence on me, and I’m just doing the best I can.” And he shook my hand and he said, “Don’t worry, old son, we all have to make a living.” I thought that was really noble of him to kind of absolve me. So yeah, so I had a few goes round on Dan Dare, but we never approached anything like the majesty of what he’d done in the early `50s.

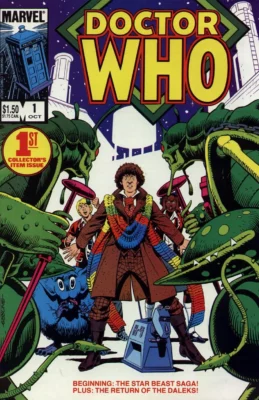

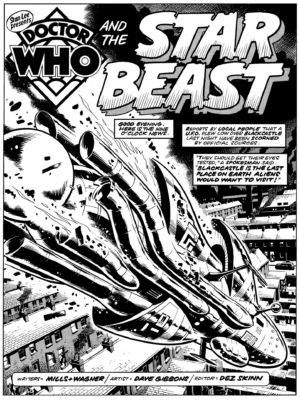

Alex: I think also the way you approached him was so humble. I think anyone would absolve you from that lead in… Doctor Who, Marvel UK. So, two questions that are really one bigger question but did Stan Lee’s hiring of Dez Skinn from Marvel UK pave the way for your involvement in Doctor Who?

Gibbons: Yeah.

Alex: What unique challenges and opportunities did you encounter working with Marvel UK and working on Doctor Who?

Gibbons: That’s interesting. Yeah, Dez had always had his eye on doing not just comics. He had this vision – magazines that could be part comic, part text, part photos. And his magazine, Starburst which I believe he originated before he went to work for Marvel which was maybe his calling card to Stan Lee was exactly that.

It reprinted that story that I mentioned earlier that I done for the youth magazine and it reprinted some other things. It had a big article in a wraparound cover about Star Wars. It was a really handsome magazine, and it sold really well considering that it was an independent publication.

And I think Stan was quite impressed with Dez because Dez, he was a great guy at selling himself. He was a good editor as well, but you know, he was full of confidence and full of what I think New Yorker called chutzpah. He was not backward in coming forward as we say. I think he maybe was a big hit with Stan Lee.

He started to be the editor-in-chief of the Marvel UK reprint organization but started to originate stuff and got British artists to work on covers, and artwork, and everything. He’d long had this idea that there should be a Doctor Who magazine because Doctor Who, although it did stop for a little while some years ago, it had run very successfully and was a real part of British tradition and culture. But there has never been a decent magazine about it. There’ve been little licensed strips in anthology comics.

So, he persuaded them at Marvel UK that he could do a Doctor Who weekly that would have comic strips, and photos, and articles. He initially approached me to say, could I ink the lead Doctor Who strip, which was going to be penciled by the art editor called Paul Neary, who’s a guy who goes back a long time in American comics. He was even, I think, before Barry Smith getting into US comics.

But I didn’t want to do that because it would only been like half a week’s work for me. I mean, I said, “No, I’ll do it but I want to do the whole thing.” And Dez said, “Okay, do some samples.” So, I did some samples to show that I could get a likeness of the actor Tom Baker, and everybody was happy with that.

Then, I don’t think a writer had been said but I said to Dez that I knew that John Wagner and Pat Mills who were the real powerhouses behind 2000 AD, I knew that they pitched stories to the BBC Doctor Who stories for the TV show that had never got made. It was thanks but no thanks.

And so I got in touch with them, and said, “Hey, you know that we’re going to be doing this Doctor Who comic. Do you want to write it?” And they said, “Yeah, that would be good”, because they could get some money back for what they, and time they spent with these pitches.

Dez thought that was a great idea as well because in one fell swoop, he was getting one of 2000 AD’s popular artists, and two of the easily most popular writers. So, we all got paid more money than we got at 2000 AD.

He done a big coup and everybody seemed to love it. It sold really really well to begin with. Sales fell off, but then they always do with any publication. It was later reprinted in the US as well, by Marvel Comics who did full color editions of it that I did new covers for.

But then it’s strange the way things go, and this, we’re now talking about late `70s, early `80s when when I was doing this… But the great wheel turns around and you sort of get back on it again. About a year and a half ago Pat Mills, one of the writers originator of 2000, we got a call from the BBC saying that they wanted to adapt one of our stories for the TV series, a story called The Star Beast. They wanted to involve us in it and make sure that we were well treated, which is a really unusual thing. It’s not the treatment comic book artists usually get.

So anyway, we went to South Wales where they were doing the exterior filming in a huge broken down steel works, and they had an animatronic, and an occupiable model of the Meep, who’s the lead character in it. A little furry, apparently very friendly little alien and they had models of of the police who were after him. It all just looked absolutely great.

I mean I’ve been on film sets before and seen my stuff become real, but this was a huge experience. I got to meet David Tenant who’s the current incarnation of the doctor. And they paid us, they made us an ex gratia payment, quite a generous one.

The show aired a week ago yesterday, as I speak to you. And it got, I think, it was 6 million viewers which in these days is a pretty, pretty good number. I’ve had all sorts of people, who I’ve lost track of years ago, phoning me up and emailing me to say, “Hey, we’re watching Doctor Who, and we saw your name come up. Congratulations!”

To be honest with you, I’m not a huge Doctor Who fan, but I think it was such a good episode of the program. It had everything you wanted from a Doctor Who story. It had the humor, and it had the action, and it had the creepy moments, and it sort of was exciting. So, we were both really, really thrilled after all that time to be associated with it again. So, who knows, they might even find a way one day to adapt some of the other stories we did, which would be a great thrill.

Alderman: How did Jim Shooter at Marvel US impact your career by paying you reprint rights for the Doctor Who series, despite not being obligated to?

Gibbons: Well, yeah. I mean that was rather unexpected. I just introduced myself to Jim at a convention and he said, “Oh, we’re reprinting your Doctor Who stuff.” And I said, “Oh yeah, that’s right.” He said, “Are we paying you for that?” And I said, “No.” He said, “Oh, we should pay you a reprint fee for that.” So I said, “Okay, great!”

So, I left my details and they started to pay me a reprint fee and then a couple of months later I got a call and Jim said, “I’m really sorry Dave but apparently, when you did the Doctor, originally in England, you signed away all your rights to it. So we can’t actually pay you a reprint fee.” So I thought, “Okay, fair enough.”

He said, “But I did personally promise it to you, so if you invoice this for professional art assistants or something like that, we’ll pay you the same money.” So, he did, which I thought was very generous of him. A couple of cynical Americans of my acquaintance said, “Well, you know, money was never Jim’s problem.”

I didn’t know him well enough to say whether that was accurate or not, but all I can say is he behaved very generously to me. So, thanks, Jim.

Alex: Yeah. And I liked your punchline with that part of your book where you said, “Sometimes, people just can’t win.” and I thought, “Yeah, that’s true.”

Gibbons: Yeah, well when you’re in a position like Jim Shooter was, where you’re in charge of the Marvel Universe, you’re going to have your wins, you’re going to have your losses. You bet your bottom dollar you’re going to piss somebody off. So, I think it’s just power for the course.

Alex: How did you get hooked up with DC comics? What were the cultural and creative shifts you experienced working on the Green Lantern Corp?

Gibbons: Yeah. Well, in the early `70s at 1972 or 73. I think it was… I went to New York with Dez Skinn, who I was very friendly with at the time, and actually took my samples up to DC… Which is a whole other story in itself, what happened there. But basically, I left them my artwork, my samples, and I got them back a few days later with “Yeah, well shows promise, but sorry, it’s not for us at the moment.”

I then went to Marvel, and actually, Roy Thomas looked at my pages and said, “We’ll get you some work”, and he never did. But really, part of that was because I was such a reserved Englishman, and I didn’t want to make a nuisance of myself in those days… I don’t mind about making a nuisance of myself nowadays, but I didn’t want to make a nuisance of myself by phoning up and going, “Oh, I’m Dave Gibbons. I left some artwork, you promised me some work.”

But all the Americans that I met since then had said, “No. The next day, if you hadn’t got anything from Marvel you should have been on the phone. You should have been…” So, I kind of got my foot in the door but I didn’t get it far enough in to stop the door shutting. But however, the samples I did for that helped with my development in jobs I got in England, so it wasn’t a complete waste.

And then, I worked as you say on 2000 AD and similar stuff, and I did a little strip in Warrior Magazine which also came out around the same time, which was hugely successful, and which premiered Marvel Man, later Miracle Man, and V for Vendetta, and so was a real… And it was edited and published by Dez Skinn. It was a really seminal work.

The guys over in New York, at DC and Marvel, both had seen that there was obviously this pool of writers and artists in England who could do stuff that was kind of inspired or based on American comics but looked completely different. It had that English kind of twist to it as some of them said, but not quite accurately, that Monty Python feel. We were viewing it in a slightly different way.

Amazingly, DC sent a couple of their managing editors, Dick Giordano and Jon Landau over to the UK, and got in touch with several of us, and asked us to go to their hotel where they had an interesting proposition to make.

So, we went along to the hotel, and they basically, after a very friendly welcome said, “Well, we’ll give you your artwork back. We’ll pay you a royalty on sales. We’ll pay you if we reprint it. We’ll even give you the Bristol board to draw it on and we’re going to pay you this much.” And even the page rate was much, much, more than we were getting in England. All the other benefits made it literally an offer that you couldn’t refuse.

So from that point on, which was I think in about 1981 or something, I’ve worked for DC Comics, and it’s amazing really because it was my ambition as a kid to be an artist at DC Comics, and not knowing how to get there. But everything came from looking at that Barry Smith’s Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. and the people I met along the way. It was just… There’s a lot of luck. There must be a little bit of me deciding what I wanted to do and what I didn’t, and a lot of perseverance as well.

But yes, so I’ve done far more work for DC, than I’ve done for any other publisher in the world, so I guess it all worked out well.

Alderman: What was your impression of Julius Schwartz, and how did he influence your career, especially during your time at DC Comics?

Gibbons: Well, Julie was the editor of all my favorite comics growing up, all the Silver Age revival – The Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, Atom, Justice League, and I love Mystery in Space, and Strange Adventures. We used to get those in reprint form in the UK as well. When I met him he was every bit the ebullient kind of New Yorker that you would expect with a kind of wicked sense of humor, and not a man to be trifled with.

He used to wear that jacket saying, “Legend in his own lifetime” which he kind of was, Julie. I think he had quite a good sense of humor about his role in the production of things. But he became very friendly with us Brits, myself and Brian Bolland, and Alan Moore, in particular, because I think frankly, he was very flattered that we were such huge fans of the comic books that he’d edited so many years ago.

He used to have a filing cabinet next to his office at DC Comics, and it was full of his editorial copies to refer to, and he obviously was coming towards the end of his career, and he didn’t need them anymore. So, I remember he had a keychain, and he unlocked the filing cabinet, and said to me, “Help yourself. What are you looking for in your comic collection?”

Because I’d already told him I’ve got nearly everything he was an editor of. I said, “Well, I’ve got the superhero stuff but Mystery in Space and Strang Adventures…”

“Yeah, sure. They start here.”

So, I start going through them and he goes, “No, no. Go old.Go old.” So I’m leafing through them and I pick up Strange Adventures #6.

“Yeah, sure. Have it.”

And then, I picked up another one… And I picked up about eight or 10 comics, and then he locked the drawer again and said, “That’s enough for this time. Next time you come, you can have some more.”

Then he did the same to Alan Moore. He chose some comics for himself. Same with them, Brian Bolland. In fact, when Brian Bolland looked through them, Julie said to him, he said, “Dave Gibbons is a big friend of yours, isn’t he?” Brian said, “Yeah” He said, “Well, you better take some comics for him as well otherwise, he’s going to be really mad that I’m starting to give comics to you. I just wanted him to know that he gets the free comics as well.”

And I can remember Brian, when I met up with him, and he came back to England deciding which ones he was going to keep and which ones he was going to give to me. And then one day, I got a brown manila envelope in the mail, from Julie in New York. It contained… And this is in my book as well, a print of this… Contained a copy of Mystery in Space #1, again from 1950 or thereabouts. And in really sort of poor condition, the cover hanging off it, and a bit torn up.

But he’d written on the front page of the comic, “To Dave Gibbons, a #1 comic for a #1 artist.” And I actually felt myself get a bit emotional because again, it was a thing that as a kid, this guy who was behind all these things that I love so much actually considered me now to be a number one artist.

So yeah, he had a tremendous influence on me. Alan Moore and I did a Superman annual for him where he treated us very well, and it’s one of my favorite comics that I’ve ever worked on. So, that came from Julie as well. And then, I remember him introducing me to a load of science fiction writers at the World Science Fiction Con in England.

So yeah, he was a good man to know. I didn’t know him for very long, and I guess I didn’t know him very, very well, but again, he was good to me, and he fulfilled every hope and dream that I might have had of meeting him when I was a kid.

Alex: Tell us about kind of your initial impressions when you first discovered Alan Moore, like kind of when you first did stuff together, which I think goes back actually to England. And then, share your experiences on working with Alan on the Superman story, For the Man Who has Everything, and the creative process for that.

Gibbons: Yeah, I do remember vividly the first time I met Alan. I was at a comic convention, one of the very first conventions that I’ve been to, where I was on the signing side of the table rather than standing in line on the other side of the table. A guy appeared at the front of the line and it was a writer called Steve Moore, who I’d worked with a little bit. And he said, “Oh, hi Dave. I’d just like to introduce you to somebody. This is my friend Alan Moore.”

I said, “Oh, is he your brother or your cousin?”

“Oh, no, no, no. No relation.” They just happened to have the same surname. I said hello to Alan. He said he wanted to be a writer and I said, “Oh, that’s great. Nice to meet you. Good luck. Perhaps we’ll do something one day.” And that was as much as I thought of it.

But then I started to see his name in print in Warrior Magazine, and in 2000 AD, and in a lot of the reprint stuff that Marvel did. And I thought, “Hey, this guy can really write. He’s got a really interesting take on it.” It’s sort of qualitatively different than most superhero comics that you read. So, I was quite intrigued.

At that time, because I was working on Doctor Who, and still doing stuff for 2000 AD… 2000 AD would give me little two and three-paged stories just to use as fillers. Just what, just to fill the issues up really. I’d work with all sorts of writers but I worked with Alan a couple of times, and I was always thrilled to get one of his scripts because they were such a joy to draw. He obviously had a, as I say, a different quality about his work.

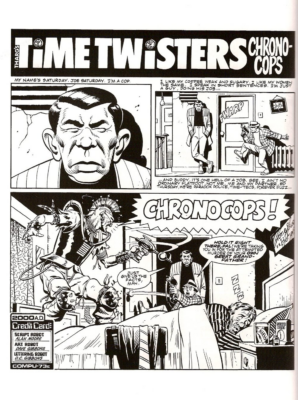

Then, we did one particular story which was called ChronoCops which was done like the MAD spoof of Dragnet. It was about these two cops who traveled space and time. They were ChronoCops. They were time cops, to stop the time streams going astray, but it was all told in this really sort of 1950s cop TV show way. It was quite a complex story to do because it involved time traveling, elements repeating themselves. So, I had to Xerox lots of bits of artwork and paste them in.

I think Alan was amazed that I was able to make sense of it and he said, at that point he was quoted by someone saying, he knew at that point that I could draw anything he asked me to, which would be very useful later on in our careers.

And so, I wanted to work with him and he’d wanted to work with me. We put together a couple of pitches for DC because by that time I was starting to do work for them, and he wrote a treatment of J’onn J’onzz: Manhunter from Mars, which would have been set in the `50s.

It’s a sort of comey witch hunt kind of mystery story with the twist, being that our detective, J’onn J’onzz tasked with tracking down the alien, is in fact the alien from Mars himself. So, you could see that could be a really interesting story. So, I spoke to somebody at DC, and they said, “I don’t know, we’ve already promised J’onn J’onzz to somebody. You’ll have to come up with something else.”

So we did. Alan came up with this really massive epic story which featured the Challengers of the Unknown, and a thing that involved all the DC characters. And again, it was the same thing… “I don’t know. We’ve already promised the Challengers of the Unknown to somebody else, so you’ll have to come up with something else.” Anyway…

Then one night, before we were able to put together another pitch, I got a phone call from Len Wein asking if I had a contact for Alan Moore, because they thought they’d like him to do some writing for them. So, I gave him Alan’s phone number, and Alan picked up the phone, and thought he was one of his English friends kind of playing a prank on him. But anyway, they eventually connected.

And then of course, Alan got offered Swamp Thing, and absolutely completely changed the game with that. He did amazing things with Swamp Thing. Then DC could see that he would be able to do something with their characters that they just bought from the Charlton Comics line. People like the Blue Beetle, The Peacemaker, and those characters.

I heard about this through a third party, I forget who it was. Although, I think it was a British artist called Mike Collins, just to give him his credit for that. And I phoned up Alan and said, “Hey, I hear you doing this sort of superhero thing with the Charlton characters, maybe this could be the thing that we did together.”

He said, “Yeah, you’d be just right for it. That would be good.”

Went to the States to my first proper US Convention, the first one that I was there as a professional. And told Dick Giordano that I’d like to draw this new thing that Alan was doing and he said, “How does Alan feel about that?” I said, “Yep, he’d like me to do it.” He said, “It’s yours.”

Literally, at the same party, I bumped into Julie Schwarz and he said, “Hey Dave, when are you going to draw me some Superman?” And I went, “Anytime you like Julie. Who’s going to be writing?” He said, “Who do you want to write it?” I said, “Alan Moore.” He went, “Sure. Fix it up.”

So, I went back to New York with the DC guys. I founded Alan from Julie’s desk and said, “Do you remember that Superman story that we were talking about some time ago? Well, DC would like us to do something together.”

“Yeah, that’d be great. Yeah, we can do that.”

So, we kind of were working on that Superman story as we were designing and coming up with all the different changes with the Charlton characters, who later became… Not the Charlton characters but characters inspired by those archetypal characters. And that was really how it started.

Alan was a great guy to work with, very dependable, very professional, the quality of his work, I don’t have to sell to anybody, you know, I mean? If there’s been a genius of comics, it’s certainly Alan.

We worked together on Watchmen for a couple of years. Basically, what we do is we speak on the phone for half a day or more just going through different ideas, and different touchstones for things that we could do. He’d then write the full script. I’d then draw the full art. John Higgins would then color it. We’d then send it to New York.

So, it was, we really did the whole thing without any real editorial input. I mean there was proof reading and stuff like that. But basically, it was just the three of us in England, just doing the comic we always wanted to do.

But again, there is more about all of these things as you know, in my autobiography, which I shouldn’t just shamelessly plug. But people are always interested in what was my working relationship with Alan, and how did we work together, and what it was like working with him.

There have been a few ups and downs in that relationship, and I just took the opportunity rather than say anything online which is always a little bit difficult. I’d actually put that in my autobiography which I felt had to be everything that had happened – good, bad, or indifferent. I wanted to think about what I was going to write very carefully because again, with the autobiography, I didn’t want to cause anymore feuds or reopen old wounds or anything like that. So, people who really interested in minutia of it, I would suggest you’d look at what I’ve written in my autobiography.

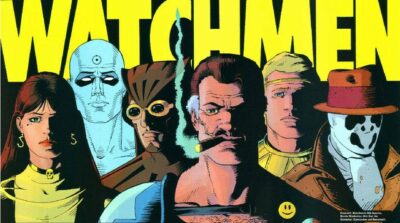

Alderman: I just wanted to tell you that I was 13 when Watchmen first came out, and I had been reading comics all my life, and I had not seen anything like it, before or since.

Gibbons: Right.

Alderman: I mean to my mind, there’s comics before Watchmen and comics after Watchmen. For our viewers who have not read the book, and maybe only seen the movie or the TV show or some of the follow-ups, you really want to go to the source material on this one. To my mind, it’s the singular greatest comic story ever told.

Gibbons: Thank you.

Alderman: And yeah, and I mean, I hold you in high esteem. I held you in high esteem before the book came out, and that just magnified how I already felt about you and your work.

Gibbons: Oh, good. Thank you.

Alex: Yeah. I feel the same way.

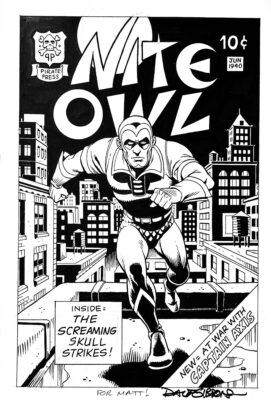

Now you had mentioned Watchmen, kind of the genesis of it. Something I thought was interesting is the Nite Owl character, the Golden Age one, was more or less your creation, is that correct?

Gibbons: Yeah, I mean, as I mentioned earlier I used to make up my own comic book characters, and one of the ones who I made up when I was a kid was called Night Owl. I think it was Night Owl spelled N-I-G-H-T Owl, and I’ve got a few drawings of him that I did from when I was… I don’t know 12 years old, something like that.

When we were redesigning Watchmen to include new characters, Alan wanted a sort of a Batman type character and I said, “I made this character up when I was a kid, Night Owl. That could really work because like you substitute owls for bats. They’re both creatures of the night and owls look pretty cool. Remember that helmet that Joe Kubert drew on Hawk Girl? that’s a kind of an owl helmet which looks pretty cool.”

And Alan said, “Yeah, that could really work. And even better if we make it N-I-T-E Owl, because that makes it kind of more American, and more kind of junky, in a way.” It’s like one of those misspellings…

Alex: Sloppy English version. Yeah.

Gibbons: It’s the English version but it’s like, I guess that it’s because they used to use it on diners and things. It be all ‘nite diner’ and it was cheaper just to pay for four letters rather than five.

Alex: Yeah. [chuckle]

Gibbons: Alan said, “Yeah that would fit perfectly.” And of course, we could give him his owl cave, and his owl ship, and his owl car, and his owl belt, and his you know…

One of the things I must say about Nite Owl, and I don’t want to spoil anything for anybody but a friend of mine at DC, Mike Carlin who’s been an editor up there for a long long time, that now works in the animation department, I think of Warner Brothers. He used to get phone calls from an inker called Al Gordon, Alan Gordon. When he kind of figured out that there was a new issue of Watchmen coming out and he’d really bug Mike.

So, when it came to the last issue where there was a little bit of a longer wait, not a huge wait, but a month maybe, he was really, really getting on Mike Carlin’s nerves. So, when the art did come in Mike Carlin doctored it. He took some Xeroxes and doctored it, and pulled it through the machine, so it was all smeared and everything like that in places. And then, he had some of the balloons relettered.

There’s one little scene in it where after everything’s done, Nite Owl and Silk Spectre, Dan Dreiberg and Laurie Juspeczyk are in Adrian Veidt’s fortress at the South Pole. They’re resting and they’re lying on Nite Owl’s cape and they’re obviously making love or they’re about to make love. But there’s a bit before it where they sort of undress it each other, and Laurie goes…

You have to understand there was a running thing in Watchmen, where there was a perfume or a cologne called Nostalgia… And so she’s undressing Dan, taking the hood of his costume off, and she goes, “Dan, that smell what is it?” And Dan Dreiberg goes, “Nostalgia.”

So, that was a very touching scene. So, Mike Carlin had it relettered, so she goes, “Dan, that smell what is it?” And Dan goes, “Al’s shit.”

[laughter]

And it’s the funniest thing I that I know, and probably the rest of you won’t be able to read that scene without thinking “Al’s shit.” So yeah, that I think, that’s the full story on Nite Owl.

Also, when it came to props from the movie, there was one prop that I really wanted, and that was the statue of Nite Owl. So actually, you can’t see it very well, but in this cabinet behind me here…

Alex: Yeah. There he is.

Gibbons: I’ve got the prop of Nite Owl. And actually, in the thing, the first night in the movie, the first night he gets his brains beaten out with this brass or steel statue. But the actual thing in real life weighs virtually nothing because it’s made of foam rubber. When it was delivered to me, when the FedEx package came, I thought, “Oh, this is the prop. This is the statue. It doesn’t weigh anything. They must have forgotten to put it in the box.” But it was there and as I say, it’s the one thing that I wanted.

The other prop I’ve got from the movie is I’ve got one of the smiley face badges that had to be specially made. Because obviously, a commercial smiley face badge when you blow it up on a big IMAX screen just looks really rough, and horrible, and smudgy. So, they handmade, hand painted, I think about four or five, smiley face badges. I think they’re worth a few thousand dollars each, and I’ve actually got one of those as a souvenir as well.

The only thing that I really wish I had asked for, and it’s probably too late now, was we did a mockup copy of the Tales of the Black Freighter. The pirate comic that runs…

Alderman: Right.

Gibbons: There… And they actually printed a very low print run of that. They used the new cover I drew, and some artwork inside, that the kids were reading at the newsstand. I really wish I had that because that is probably the rarest Watchmen comic you could imagine.

Alex: In the original script that Alan wrote, was the character called the Nite Owl in that script?

Gibbons: Yes.

Alex: Okay, because you guys had talked about it before.

Gibbons: Yeah… No, we’d come up with all the Watchmen characters before he wrote the first script and I’d done the character designs.

Alex: There you go. Okay.

Gibbons: So yeah, he was always Nite Owl. There’s never ever scripts or anything written with the Charlton characters in it. So, yeah. That’s the answer.

Gibbons: Uh-hmm… Old interviews with Alan that I’ve watched, he mentions that you guys were kind of going through the first couple issues, then by the third one, a magic started happening where you guys really were synergizing together, on telling this 9-panel grid story and there was something, almost a new life had come about.

And you’re describing it in your autobiography, in much more detailed terms, which everyone needs to read. But in a quick summary, is that there was a fandom developing around it and you guys were at the heart of this, almost the target of this intense fandom which, interestingly, almost became something that contributed almost just wanting to like almost not see each other and just do other stuff.

Maybe everyone will focus on the new stuff, and culturally, everyone keeps focusing on Watchmen. As the media adaptations have occurred with it, it seemed like you more embraced it, and he distanced from it, and that contributed to a little bit more of a personal separation.

As you’re going through that in real time, were you saddened by that? Was it like a high, and then a low? Or when you look at the whole thing, are you glad the whole thing happened?

Gibbons: Well, I’m glad all the positive things happened, of which there were many. I obviously, I’m sad that there were negative aspects to it which kind of came in to play. But we had tremendous fun doing it. We really couldn’t believe the initial reception.

I remember when we went to New York together, and we arrived at the DC offices. It was really like we were visiting royalty. People were coming out of their offices to shake us by the hand, pat us on the back, and we really thought, “Wow!”

Because as I’d said in an earlier answer, we’d be doing it in England, with no real contact with the editor at DC. But everybody’s seen it. Gil Kane, I remember, had seen it and kind of shook me warmly by the hand. “Great artwork, my boy.” which he called everybody “my boy”, but I was his boy.

It was just a knockout. And then of course, the next thing that happens, you think, “Oh my God, we’d done three issues, we’ve got nine more to go. People are expecting something wonderful.” So there was a lot of deadline pressure to get everything done on time.

And also, DC moved the deadline up, because they wanted to get it out for various commercial reasons. That put a real squeeze on us, and it did mean that the very last couple of issues were probably a month or so late. They weren’t hugely late. People got it confused with Brian Bolland doing Camelot 3000, which was I think a year late or something like that. But if we kept to our schedule, we’d have finished on time, and everything would have been on time.

So, there was that tremendous pressure that we had to make it good. And I remember, I used to think, “Until I’ve drawn that last page, we really haven’t got anything.” Because by the nature of it, they couldn’t get a new writer in, and they couldn’t get a new artist in, because we’d established a look and a style of storytelling that kind of only we could do.

So, there was that to it, but I mean, I was friendly with Alan for a long time, and we did at the beginning of it all, we had meetings with film people about making a movie of it, and Alan was quite gung-ho about that. We both collaborated with doing a role playing game, so it wasn’t an issue.

There was certain misunderstandings about the contract we signed, which again, I go over in the book. But basically, it’s a thing that Alan sees as something malign, that it was an attempt by DC to take something from us.

But my view of it has always been that it was a standard clause in the publishing contract, which meant that to the benefit of writers of fiction that if an edition wasn’t published by their publisher, they could apply to get the rights to it back. So, they could then go on and sell it to another publisher, which seems to me, not an effort to steal something from the creators but rather to give them a certain insurance that they would be able to continue to make money from it if the book was publishable.

There was that. That rankled with Alan. There was some silly little disputes as well about very small sums of money that I know really pissed Alan off and they pissed me off as well. But it was really as time went on, you know, and saying that I was under pressure to do Watchmen well.

Alan was also working on Swamp Thing. He was working on a load of other things and again, he was expected to perform at a really high level. I think that was kind of stressful. But even after Watchmen, we later went on to do things together. We worked on 1963, which was this sort of past stage Marvel tribute comic that Alan wrote.

Alderman: Great book!.

Gibbons: It is one of the great unsung wonders of comics. It’s a shame we never got to finish it off. They never did that last issue, but again, for disputes that are way outside anything that I’d want to talk about. It doesn’t look like that’s ever going to happen, which is a tremendous shame. I understand it. I get it. But it’s still a shame.

Alan and I also worked on The New Adventures of the Spirit (Spirit: The New Adventures) where we got to be Will Eisner for an issue’s worth of comics, which was a great thrill. But then yeah, for various reasons, which again, I go into in a considered way in my autobiography, we drifted apart and eventually, our friendship failed which is a thing that I regret because I greatly valued Alan’s friendship.

It was with a heavy heart and it was much, much more in sorrow than in anger that we reached the parting of the ways. And it’s now been… God it’s must been 12 years, more than that since I spoke to Alan. I mean he’s got plenty to do, and he’s perfectly busy, and productive outside comics, but I’m just really glad that I got to do the collaborations with him that I did, which are undoubtedly the high spots of my career.

Alderman: What were your thoughts about Watchmen being named one of the Top 100 Novels of the 20th Century by Time Magazine?

Gibbons: That was a surprise. I mean some cynics pointed out that Time Magazine is published by Warner Brothers, who own DC Comics. So, that rather brought me down to… But I mean, I think apart from anything, the fact it’s something that I worked on that got to that position, I’m obviously thrilled about, and very, very flattered by.

And also, it’s just good to see that a graphic novel or a comic book essentially could make it into that sort of company. I mean, there’s some incredible classics of Western literature in that list. I take it with a little pinch of salt, but nevertheless, I’m very flattered. And yeah, I mean… Yeah, if they think it’s worth putting in a list like that, who am I to say isn’t?

Alderman: [chuckle] And how do you feel about the various adaptations of Watchmen in other media? Movie, HBO show, DC Meets Watchmen… What are your thoughts on how these adaptations have diverged from the original work?

Gibbons: Yeah. Well, there’s a few different things going on there. You’ve got the movie adaptation which was a straight adaptation from one form into the other, which is basically, it follows the same story. It’s got a slightly different ending, although the ending makes sense, and I think although the ending for the comic book was great, it made sense to change it in the way that they did for the movie of it.

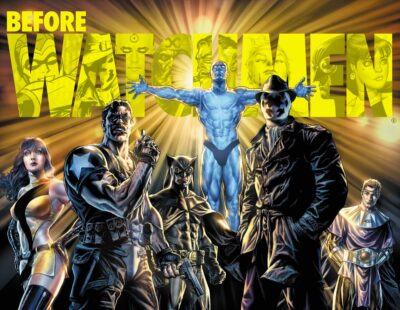

You then got Before Watchmen which was sort of a prequel which kind of I thought was unnecessary and to me is a little bit like explaining a joke or something like that. Everything you needed to know about Watchmen, we put in Watchmen, and to go back and explain or look at things blow by blow what had happened in the past… I couldn’t really see the point of that.

I mean, they had some great people working on it and I haven’t ever actually read them. I flipped through them and there’s some really nice artwork in there. And again, going back to the thing that I was saying about Frank Hampson, if people want to contribute to something like that because they’ve got the love of Watchmen, who am I to say that as fellow freelancers, they shouldn’t. So, I bear nobody any grudges or ill will about it. It’s just I probably… And I got offered the chance to participate in it but I really wasn’t interested.

The Watchmen TV series to me was set so far in the future of Watchmen that it sort of, it was just an extrapolation. It wasn’t “Yes, this is what happens”. It’s “Well, maybe if you drag things forward, this is what could have happened.”

I was prepared not to like it at first, although they were very gracious in the way that they approached me about the fact they were doing it. But when I came to see it I thought this is so well done. This is teaching me things I didn’t know about American history. They’re doing things that I can only look at them and think, “My God, why didn’t we think of that”. So, there was a lot of good work went into that which I enjoyed.

And of course also, Warner have announced that there’s going to be a animated version of Watchmen, which I have to tell you, I have seen bits of, and I’m absolutely astounded by the quality of the animation on it. It almost looks like it’s my drawings, my actual drawings brought to life.

And although we know, we’ve got Watch(men) Babies, and all these sort of spoofs of Watchmen done in an animated style, it actually kind of makes sense, because the thing about the comic book that we did originally, was it looks quite innocent. It just looks like a comic book. It’s not particularly challenging, the page layouts. But when you actually read it, you think, “Hold on a minute, these aren’t the comics that I’m used to reading.”

I think it would be the case with the Watchmen animation as well, which is heavily, heavily stylized, which looks like a children’s animation but obviously when you read it, and when you see what’s unfolding, it has a completely different feeling. So, it’s a weird kind of R-rated animated feature, and no doubt people will like it, and no doubt people will hate it, but I actually I like it.

Alderman: Did you have any thoughts about when they brought the Watchmen characters into the DC Universe?

Gibbons: Of course, yeah, there was that. That was the other thing they did, wasn’t it? Doomsday Clock. I couldn’t see the point of that. I mean, DC have got so many characters,so many. Why do they have to merge Watchmen with that? To me, it makes no sense at all. I’d much rather have seen some somebody taking a new approach or a new storytelling approach to DC’s existing characters. There was a thing that I sort of, that Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely did for… Multiverse, was it? The Multiverse or something…

Alderman: Multiversity, I think?

Gibbons: Yes. Where they’d done a treatment of some characters and they’ve done it in like a four-dimensional way where they’ve been very aware of the storytelling, and the layout, and did lots of interesting little narrative tricks. That’s the sort of thing that would excite me about seeing the DC characters involved.

But to me, it made no sense at all other than financial, to merge those things together… And I’m not sneering at financial. I know that Warner Brothers is a company that’s supposed to make money, but it’s a shame sometimes when they end up doing something which is sort of from a literary point of view or from a creative point of view, not such a good idea in the long run.

Alex: When I watched this HBO series, I loved it. I thought they did some hard-hitting stuff, but one thing I felt was, finally we see the squid at the end and it was such a… And the psychic horrible feeling of its manifestation. Do you feel like Zack Snyder missed out on not doing that?

Gibbons: Not specifically the squid. I was saying to somebody the other day, that actually there is a squid at the end of the Watchmen movie. Because he does this weird thing that involves Doctor Manhattan, and it’s all about energy, which is great. But when Adrian Veidt presses the button to make whatever happens happen, when you see the power console that he’s at, there’s actually some technical writing on it and it says something like, “Sub-Quantum Unit Interference Deflector”.

It’s some scientific thing which of course, spells out the word squid. So, the squid is there, and Zack Snyder was not carefree. “Oh, let’s just cut the squid. I don’t like the squid there.” There were good reasons for it, and it saved on extra storytelling in an already long screenplay, because you’d have to do all the background of the people on the island, and writers, and the artists, and the biologists creating this squid.

And also, it would have been another special effect. I mean essentially what happens in Watchmen is, it’s a huge special effect that Adrian Veidt pulls up… But in the book, in a story that’s full of, or movie that’s full of special effects it would have just been one more special effect. So, it wouldn’t have had that

that impact.

But I think, yet again, the way with Watchmen HBO thing, the way they did it, was to keep some of the very clunky costume designs, and make the whole thing feel like it was a straight adaptation of the comic. As if you were seeing something that was just happening offstage in the comic. So, I thought that was very cleverly done.

And again, because it was all my costume designs, I was thrilled to see them actually there in the flesh.

Alex: How did you navigate the transition to focusing more on writing, and inking, in the 1990s? Just writing is a very different thing, and you’re obviously very well spoken, very good writer. How did you navigate that transition? How do you find that as far as personal satisfaction compared to the drawing?

Gibbons: When I was growing up, as far as I knew, it was all done by one person. They wrote the story. They lettered it. They drew it. They colored it. I had no idea at that stage that… So, my ambition was not just to do DC Comics but to do everything about them. To sort of write them, draw them, at the same time.

So, nearly everything I drew as a kid was drawn as part of a comic strip I did very few kind of pinup shots, you know, the hero standing there looking brave, and everything like that. It was always the story that fascinated me.

I might not have gotten very far. I might not have gone beyond the bottom of page two but the instinct was to tell stories as well. And I’d always had a yen to write things, and so, whenever I was offered anything to write, I would take it, just to try out my writing.

I found that I actually enjoyed doing it and it was a different challenge than drawing because drawing is very heavily to do with craft and manipulation of objects, and materials, whereas writing is much more cerebral, much more thoughts, much less bogged down in the technique of how you get it down there.

So, I found it came quite easy to me, and as you discerned, and with my autobiography, I am a man of many words. I love words. I love to get the right word. I love to tell people little stories and anecdotes.

Again, as you can tell from my autobiography, and again, Mike Carlin, because he saw a little thing that I did for magazine called A1, which was a story called Survivor, drawn by Ted McKeever. It was a sort of a bleak and dark take on what it meant to be super heroic. But Mike saw that… That I’d done for no money. I’ve just done for the fun of it, to do something with a friend of mine.

He said, “Hey, how would you like to write World’s Finest, Superman-Batman team-up.” I said, “Absolutely! Yeah. Who’s drawing it?” He said, “Steve Rude.” I said, “Sold. Yes, I want to do that.” So, that was really my first major writing gig which you know, to work on Superman and Batman straight out the gate with a really great artist was very flattering. I really enjoyed doing that.

So, I actively looked for more, and more work, and I guess I must have done okay, because again, on the strength of the jobs I’d done, I was offered more work to do. Until I ended up writing and drawing my own thing completely with The Originals, which was again, kind of semi-autobiographical.

But the thing I discovered there though was that although I love to write, and I love to draw, that actually to do both is a little bit lonely. You’ve got nobody to compare notes with. You’ve got nobody to get feedback from. Being a sort of an artistic type, you sort of fret, and worry whether what you’re doing is any good, whether anybody really cares about it.

So, I found that a bit hard that in the end, I got the editors at DC to phone me up once a week and ask me which page I was on, and I’d be shamed into actually making sure I’d done at least a couple of pages so I could tell them I moved on. But again, as it happened in the end, it was very well received. I actually got an Eisner Award for it, which was amazing to me.

So yeah, so I do love to write. I greatly enjoy doing my autobiography. I’ve got another couple of projects that again, I won’t jinx by saying anything here, that I’ve got a lot of writing in them. So, I guess it’s me discovering a talent that I’d always had. And again, very refreshing because it’s a whole different set of mental muscles.

Alderman: On The Originals, it stands out as a significant work in your career, earning an Eisner Award. Could you share the inspiration behind the graphic novel? I know you touched on that a little bit. What’s the process of creating it was like for you? How does this recognition reflect on your evolution as an artist and storyteller?

Gibbons: Yeah, I mean, The Originals is really quite an autobiographical thing. It’s basically like a sort of science fiction Quadrophenia because when I was growing up, I was a mod. I had the scooter, and I had all the clothes, and I had the haircut. I had hair as well.

So, Karen Berger would pester me. She’s a very good friend of mine to say, “Dave, when are you going to write and draw something for me? You really should write and draw something complete.” And I thought, “If I’m going to do that, it’s got to be something that I really care about. I can’t just do another science fiction or another superhero.”

And I had a few experiences that was still stayed with me from the days when I used to be a mod. It wasn’t anything really serious, there was no guns and never any knives involved, but there was a lot of battling and skirmishes in the streets between rival groups from different neighborhoods. And I thought, “Yeah, there’s something there that still means something to me after all this time.”

So, I decided to do that. I wrote my notes down with a lot of things that really happened being in there, but slightly adapted to make them dramatically more plausible or more interesting. I actually wrote the whole thing as a movie, as a screenplay, without breaking it down into pages. So, I wrote the whole thing, scene after scene after scene, and then broke it down to being a comic book.

It turned out to be exactly the right length for a 120-paged graphic novel. So, I thought obviously, this was meant to be, I’ve written exactly as much as was needed. And then, I got a bit of editorial input from Karen on that which improved it, and then I started to draw it, and it became a little bit of a production line because it’s done on a grid again.

But now, I had the use of a computer which meant I constructed the grids on a computer, and did the lettering on a computer, printed it out to draw over the top of it. Then rescanned it in, and used Photoshop to put gray textures in it and everything. I wanted it to be in black and white because again, that gave it that slightly retro feel, and could look quite sharp and stylish, because it’s very high contrast.

So, that was basically the way I did it, but as I say, it was a hard slog and at that time… You can see my spacious studio with lots of windows behind me now but… Yes! Look at that. That’s because I did this.

[chuckles]

That was pretty good. I couldn’t have planned that. I’d have got the timing…

Alex: That was amazing… See that’s the triple Eisner Award winning David Gibbons demonstrating his talents effortlessly. Incredible.

Gibbons: Yeah… But the office I was working in at the time, it didn’t even even have a window. It had a skylight. All I could see was a square of skies. So, it was a bit like being in prison or being in a monastery or something like that. So, that did concentrate my mind, but as I say, it all turned out well in the end.

I’ve got a little bit of an idea about a possible sequel or last act to it, so I’ve been having thoughts about that as well. So, we’ll have to wait and see what happens.