Al Williamson: Comics Illustrator by Alex Grand

Alfonso ‘Al’ Williamson, comics illustrator, left an indelible mark on the comic industry, shaping the narratives and styles that continue to inspire artists today. Born as Alfonso Williamson Perez Jr., the young artist found his home not only in the verdant beauty of Colombia but within the captivating realm of comics and illustration.

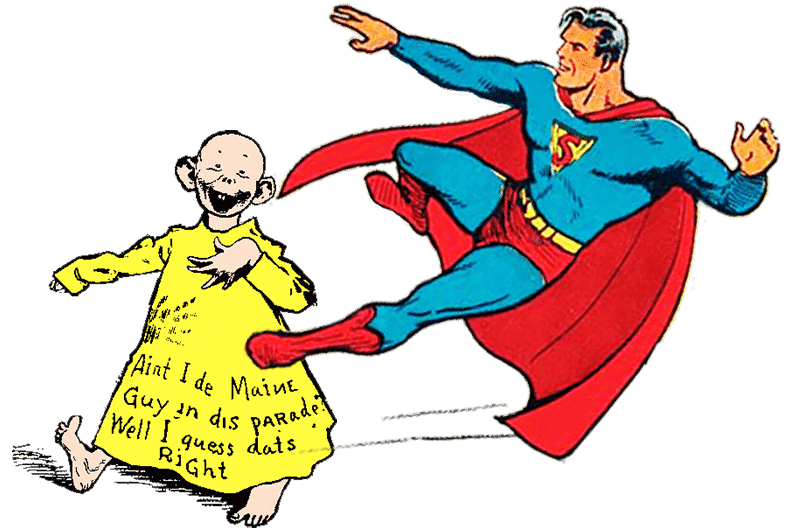

He came to New York City at age 12 and immediately became fascinated with the 1940 movie serial, Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, ignited a passion for visual storytelling that would define his career.

At the tender age of 17, his portrayal of Flash Gordon in 1948 exhibited a sense of realism that would become a distinctive feature of his later work.

Williamson’s dedication and creativity facilitated his rapid rise within the comic art industry in part from keeping his eye on the artists of the past. As he once noted in The Comics Journal, his work bears subtle traces of architectural influences, notably those found in Franklin Booth’s Unseen Foundations (1925) and Flying Islands in the Night (1913).

In the 1950s, Williamson began to distinguish himself in the field of comic art. His work on Atlas’s ‘Jann of the Jungle’, created in collaboration with Ralph Mayo, encapsulated the aesthetic tendencies of the Tarzan obsessed era.

Even at this juncture, Williamson’s passion for space fantasy shone brightly. He created a preliminary cover for Weird Fantasy 13, which, although unused, would later be reconfigured for the final cover of issue 21 in 1953.

Concurrently, Williamson was engaged in social activities with other members of the EC Comics bullpen, including Marie Severin, who later gained renown as a Marvel artist.

Although EC Comics was known for its shocking horror comic books, Williamson preferred Science Fiction.

Williamson’s contribution to ‘Tales of Suspense 1’ in 1959 served as an early demonstration of his affinity for space exploration narratives. This issue featured a space dragon, starships, and a blonde hero, hinting at his future involvement in Flash Gordon. His work at this time was not only notable for its artistic achievement, but also prophetic of his trajectory in the comic industry over the ensuing years.

By the mid-1960s, Al Williamson was poised to reinterpret the character that had initially catalyzed his artistic journey.

In ‘King Comics Flash Gordon 1’ released in 1966, he seized the opportunity to carry forward the narrative of Flash Gordon, deftly capturing the sleek heroism of Alex Raymond’s original concept while incorporating contemporary science fiction elements. The introductory pages served to encapsulate the overall narrative arc of Raymond’s original Sunday newspaper strip, thereby bringing it to its conclusion within the pages of this comic book.

This narrative decision essentially superseded the continuity of the newspaper comic strip for succeeding creators, including Mac Raboy, who worked on the Sunday strip from 1946 until his death in 1967.

Williamson’s art was immediately hailed by fans and critics alike, with issue 4 from 1967 even featuring in a Colombian newspaper clipping when Williamson was only 36 years old.

He meticulously penciled three extraordinary issues of Flash Gordon for King Comics in 1966, extending the Alex Raymond narratives with the collaboration of Archie Goodwin.

In the case of Flash Gordon 4 from 1967, he captured a self-portrait, before drafting and inking the final image that would be used in the issue.

His rendition of Flash Gordon was rapidly gaining cultural significance, a status cemented by its use in promotional materials for Union Carbide Plastics in 1970. This period saw Williamson’s vision of Flash Gordon evolve into a cultural touchstone.

His next professional assignment in 1967 was on another property started by Alex Raymond, the newspaper comic strip, ‘Secret Agent Corrigan,’ which under his hands exhibited a cinematic grandeur, with each panel possessing a unique aesthetic that contrasted well with Archie Goodwin’s dynamic storytelling style.

His illustrative approach matured significantly during this period, as evidenced by his evolving depiction of Secret Agent Corrigan. Initially, he modeled the character after Alex Raymond’s style, then shifted to emulate Sean Connery, and by 1971, he had infused the character with elements of his own likeness.

Collaborating once more with Archie Goodwin, Williamson transformed the Corrigan series into a narrative rich with suspense, intrigue, and action. This narrative depth was especially apparent in gripping storylines, such as the 1969 plot involving the kidnapping of Corrigan’s wife. This storyline, which bears a resemblance to themes later explored in films like ‘Taken’, depicts cock-eyed kidnappers who failed to realize her husband happened to be one of the greatest secret agents in the United States, and nothing was going to get in the way of getting her back.

In the 1970s, Williamson continued to explore a diverse range of genres. Notably, he captivated audiences with an intriguing blend of James Bond-esque narrative elements with science fiction undertones in the ‘Secret Agent Corrigan’ strips. This unique fusion proved to be a resounding success, further demonstrating Williamson’s versatility as an artist.

The 1970s represented a period of growth and exploration for Williamson. His work on ‘Secret Agent Corrigan’ ventured into a broad array of narrative genres and geographical settings, an innovative skill he proudly showcased at the 1973 Lucca Comics & Games festival.

That same year, he incorporated a depiction of a Buddhist Tibetan lamasery into his work, reminiscent of the origins of iconic characters like Green Lama, Dr. Doom, and Dr. Strange.

Another 1973 strip demonstrated Williamson’s deft handling of the spy genre, as Corrigan enticed a local baroness and engaged in a deadly duel on a cliff edge, his survival hanging in the balance.

In 1974, readers were introduced to Lady Vengeance, a character whose father’s murder at the hands of mobsters spurred her transformation into a vigilante targeting criminals. Her persona resonates with that of Elektra, who would debut in 1981. Though Lady Vengeance’s aesthetic leaned towards a more “Gimp with a Gun” style rather than the typical ninja look, both characters underwent rigorous training and pursued ruthless mobsters.

As the series evolved, it explored more mature themes. For instance, a 1975 episode finds Agent Corrigan journeying through the ‘Cheap and Gaudy’ section of town.

In the same year, another storyline involved Corrigan exploring a South American Pyramid in search of an ancient totem.

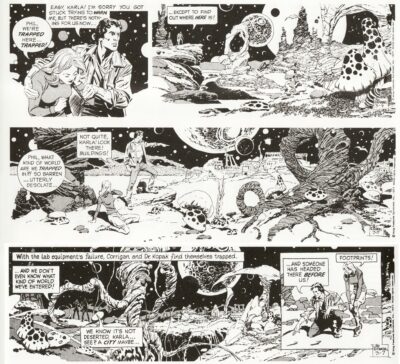

Intriguingly, Williamson also incorporated extraterrestrial encounters into the narrative, as Corrigan meets an alien preserving a lost civilization in Antarctica.

The cultural fascination with cults in the 1970s is embodied in a 1975 strip where Corrigan confronts Madam Satan and her Church of Darkness, a storyline that seemingly drew inspiration from the film ‘Rosemary’s Baby.’

When the narrative took a turn towards science fiction, it was clear both Goodwin and Williamson reveled in exploring this genre. Williamson’s creative zenith in 1975 was self-referentially depicted in a panel from Flo Steinberg’s Big Apple Comics, showing him at his drawing board.

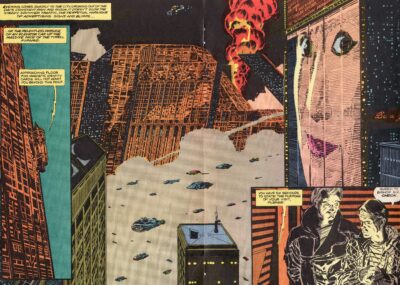

In 1977, the series embraced elements of space travel and alternate dimensions, with Agent Corrigan traversing dimensions in several intricately detailed dailies, boldly venturing into new narrative frontiers that set ‘the controls for the heart of the sun.

The ‘Secret Agent Corrigan’ series reached a climactic conclusion in 1979, as Al Williamson and Archie Goodwin pulled out all the stops for their final science fiction escapades.

The emphasis on science fiction was echoed the same year in Steranko’s Mediascene 40, a publication in which Williamson appeared to revel in a renaissance of the genre.

As the series ushered in the new year, hinting at the dawn of the 1980s, Williamson transitioned from the strip to collaborate with Goodwin on projects at Marvel, including film adaptations and Star Wars. During this period, Williamson also crafted the artwork for the Flash Gordon Movie Adaptation comic book.

Soon after, he embarked on adaptations of iconic films like ‘Star Wars: Empire Strikes Back’ in 1980 & ‘Blade Runner’ in 1982, both with his long-time collaborator/writer, Archie Goodwin and finisher Carlos Garzon.

Gooodwin did a great job adapting the script for comic book form and it took this team 3 months to make it among their other projects.

The story itself is of course beautiful, and points out that life is to be enjoyed and savored no matter how long or short it lasts, and that even an android can have daddy issues and cry.

Williamson’s contributions to the ‘Star Wars’ franchise were particularly noteworthy.

His 1980s ‘Star Wars’ newspaper strips, created in collaboration with Goodwin for Marvel, were reprinted in ‘Classic Star Wars 1’ in 1992, a testament to the enduring appeal of his artwork.

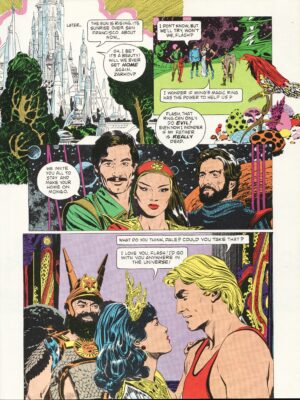

His subsequent work on a ‘Flash Gordon’ mini-series for Marvel in 1995, where he completed two issues, illustrated his continued artistic development, even as he returned to familiar themes and characters.

The interior back cover featured the planet Mongo in the backdrop, a sword duel with Ming, and a homage to Alex Raymond’s original in the final page.

As Williamson’s career transitioned into early 2000s, he worked on two Sunday editions of the Flash Gordon newspaper strip in 1999 and 2001.

The first was a collaborative effort, while the second was entirely his own creation. At the age of approximately 70, Williamson’s talent remained undiminished.

Despite his semi-retirement, Williamson’s engagement with his craft never truly ceased. He provided inkwork for Marvel’s ‘Spider-Man’ and ‘Daredevil’ titles, demonstrating a keen eye for detail that remained sharp and effective.

His talent was formally recognized when he won an Eisner Award in 2000 for his contributions to ‘Blade of the Immortal’, a fitting accolade for an artist of his calibre and dedication.

The news of Williamson’s death in 2010 left a void in the comic industry. His stunningly visual storytelling technique and fluid style had touched many a reader and inspired countless artists. From his early works to his late-career masterpieces, Al Williamson’s legacy remains as a paragon of comic artistry, embodying a remarkable blend of imagination, precision, and creativity. He left behind more than a body of work; he left a path for future comic artists to tread. He showed how to weave visual narratives that resonated with readers, his art dancing across the pages with a mesmerizing sense of depth and vitality. His legacy is a testament to a life lived in the pursuit of creative excellence and a passion for storytelling that spanned seven decades. A life that continues to inspire and enlighten in the annals of comic history and beyond.

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out our CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.

Images used ©Their Respective Copyright Holders