A Boy and His Dog on the Road to Hell: Lone Wolf and Cub #19 by Anthony M.Caro

Itto Ogami lets fate and the “blood of the Ogami clan” guide his son Daigoro’s destiny. In the opening chapter of the “baby cart assassin’s” tale, reprinted by First Comics in Lone Wolf and Cub #1 (May 1987), the soon-to-be Ronin places his son between a sword and a child’s ball. The cruelty that hangs over the series guides the less-than-one-year-old Daigoro’s actions, and Itto Ogami waits to see where the baby crawls. If the young one reaches the sword, he stays by his father’s side. Choosing the ball means the child wishes to be with his mother, and the assassin will decapitate his only son. Daigoro takes the sword, leaving Itto Ogami to quip, “You would have been happier at your mother’s side…My poor son.”

The First Stories Before First Comics

Many fans in the west first met Itto Ogami and Daigoro in the 1980 release of Shogun Assassin, a film that edited together two Japanese films made in 1972, Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance and Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart at the River Styx. In the late 1980s, First Comics connected with Frank Miller to produce the first English translations of the source material: Lone Wolf and Cub, a massive manga by writer Kazuo Koike and artist Goseki Kojima published in Japan in 1970. First Comics did a tremendous job releasing the first 45 chapters, but the series ended long before concluding. Fans waited many years for a complete English translation. Eventually, Dark Horse released the complete translation in a mega 28-volume trade paperback series from September 2000 until December 2002.

The “Baby Cart” saga proves transgressive and unnerving. The cold relationship between Itto Ogami and Daigoro underlies the father’s stoic desire for vengeance against those who murdered his wife. Daigoro, an innocent child, absorbs all the homicidal brutality surrounding him. Revenge and the road to hell reshape Itto Ogami and Daigoro’s lives. The father remains emotionless, having lived a violent existence, realizing that there’s no good way his story ends.

Daigoro has yet to understand the world entirely, serves as a passive observer, never fully emotionally affected by the events. That would change in the story taking place early in the epic tale.

The Road to Hell Widens

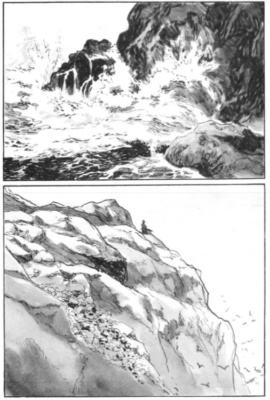

The story “The Town Where Hunger Lives,” featured in Lone Wolf and Cub #19 (November 1988), reveals the all-encompassing scope of meifumadō, “the road to hell” to both Daigoro and the readers.

A recurring theme in the Lone Wolf series centers on how quests for vengeance result in ruin. The road to hell leads to more self-destruction than an eventual loss of life. That’s not the road to hell. That’s the dead-end destination of the road. The “road” refers to the journey involving continual pain and suffering. Detours might exist on the road, but returning to the path becomes unavoidable. Once someone chooses the road to hell, joy, happiness, and everyday life become fantasies, even for a small child and his pet dog.

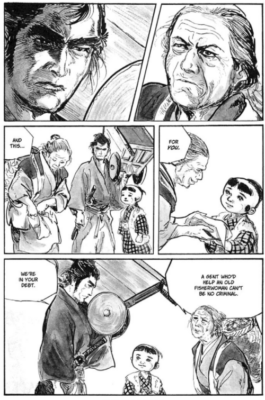

Daigoro’s relationship with the dog provides a playful counterbalance to his detached paternal relationship. While Itto Ogami may be a cold and calculating assassin, and although a seemingly emotionless father, he is not unloving. Itto Ogami understands that young Daigoro is only a small child, but the young one chose meifumadō, denying himself a normal upbringing. Itto Ogami realizes the only way to raise Daigoro properly involves forcing him to grow up fast. Otherwise, he won’t appreciate the dangers, and he won’t last.

Still, Itto Ogami’s an assassin who kills for money. Lines exist that he won’t cross, and Koike’s writing focuses on Ogami killing immoral characters who brought about their fates. Koike has no choice. Otherwise, Itto Ogami would be a villain and a less compelling protagonist.

Itto Ogami’s detachment about the assassin’s road depicts a bloody profession like a bloodless job. Itto Ogami kills, but he does not relish in sadism. The character’s detachment reflects not only a sword for hire but a perpetually lost soul. Daigoro hasn’t lived long enough to become as cynical as his father, but world-weary cynicism will befall him soon.

Perhaps Itto Ogami wants Daigoro to become used to death since he realizes the child will soon be without a father, maybe sooner than expected.

Daigoro deals with adult trauma as he travels a traumatic road. Daigoro finds himself lulled at times into thinking he can enjoy things other children do. Such is not the case when walking meifumadō. The 19th chapter in First’s reprints shows the harsh and unavoidable lessons the young one inescapably learns.

A Hunger for a Normal Childhood

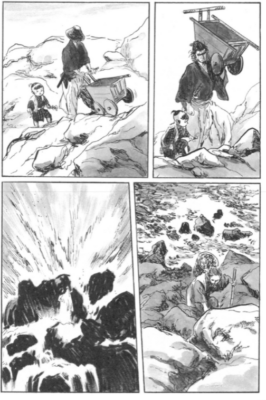

“The Town Where Hunger Lives” presents a twisted version of a traditional “boy and his dog” story, one that curiously begins with Itto Ogami seemingly torturing a small dog by shooting with blunt arrows. The arrows sting, but they don’t cause harm. The little dog suffers through his pain until comforted by Daigoro.

The road to hell is a solitary path. Itto Ogami, old and jaded, accepts loneliness. Daigoro lacks the world-weariness of his father, and he also lacks friends and companionship. The boy takes to the dog, and Kojima’s stunning artwork captures the love Daigoro has for his new and only friend.

Later, Daigoro and the dog sleep side-by-side near Itto Ogami. Kojima’s artwork’s tone shifts, capturing the eyes-wide-open father who cannot sleep, for he knows the pain to come for Daigoro. Itto Ogami’s lack of emotion contrasts with Daigoro’s joy, but the contrast isn’t lack of emotion vs. emotion. Ogami feels sadness and pain about what’s to come, or else he wouldn’t lie awake staring internally.

What drives these actions?

A Demon-Haunted Village

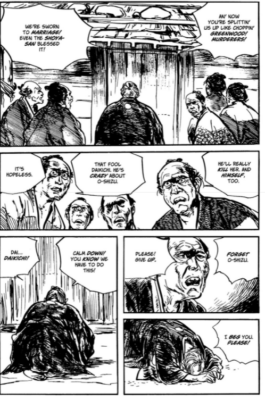

Itto Ogami and Daigoro travel to a nearby town and discover why hunger lives – a castle lord contemptuously called the “Red Demon” resides there, and his cruelty and corruption prevent the townspeople from receiving any rice during a terrible drought. While the townspeople suffer from starvation, the lord demon enjoys games of dog hunting. On horseback, the lord uses his archery skills to kill dogs before they can escape to freedom.

Itto Ogami has been training a little dog to evade arrows, with the hope the Red Demon’s more challenging hunt will draw him from the castle’s protective boundaries. The Red Demon may hunt dogs, but Itto Ogami intends to hunt him.

Lonely Daigoro finally made a friend with the little dog, turning an assassin’s game intended to deliver deserved justice to an evil man into a tragedy. No spoilers, but readers can surely figure out where his chapter’s road leads.

Daigoro chose the sword, and now he must live by it. Having a beloved pet dog that grows up with him never fits into the plan. Daigoro has to become strong enough to handle the hard road ahead of him, one he will eventually travel alone. Numbness to death and violence could make him handle the road better, as does handling tragedies and becoming expectedly emotionally distant.

“The Town Where Hunger Lives” might be the most heartbreaking of all Lone Wolf and Cub chapters. Most wrenching is the conclusion’s effect on Daigoro, as we see the first hint of Daigoro’s acceptance of the road to hell. He’s no longer a baby.

Anthony M. Caro wrote the essay collection Universal Monsters and Neurotics: Children of the Night and their Hang-Ups and the sci-fi serial Why Does Cal Draw Stick Figures at 3 AM in the 22nd Century? for Amazon Kindle. He writes about all things pop culture and contributed to HorrorNews.Net, PopMatters, Mad Scientist, and Jiu-Jitsu Times. Besides working as a professional writer, he handled production duties in radio, TV, film, and theater. He’s currently developing an audio drama podcast.

essay ©2023 Anthony Caro

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out our CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.

Images used ©Their Respective Copyright Holders