Visualizing Robert E. Howard’s “The Tower of the Elephant” in Conan the Barbarian #4 By Anthony Caro

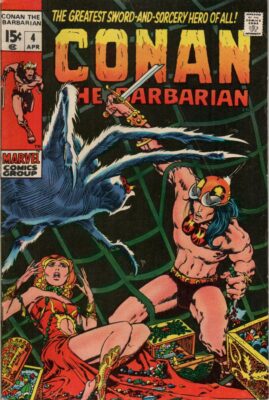

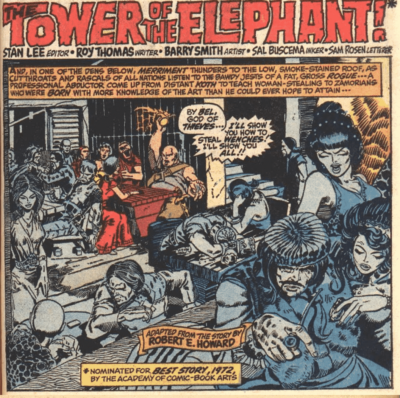

“The Tower of the Elephant” ranks as one of Robert E. Howard’s best Conan yarns. Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith deserve enormous credit for effectively translating the 30-odd page pulp tale into a 20-page comic book. Crafting a tighter, visualized version of the narrative garnered Thomas and Windsor-Smith (then credited as Barry Smith) a “Best Story, 1972,” nomination from the Academy of Comic Book Arts for the adaptation published in Marvel Comics’ Conan the Barbarian #4 (April 1971).

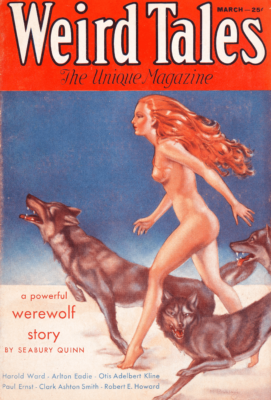

Although abbreviated, the duo’s Bronze Age classic captured the spirit and underlying emotional impact of the original prose published in the March 1933 issue of Weird Tales.

Tightening the Tower

1970s era comic books focused on fast-paced action, so the Cimmerian fit perfectly in the Marvel Comics publishing slate. Conan does not speak in a nuanced manner. He says what is on his mind and, more frequently, commits to action. In his prose, Robert E. Howard also spoke his mind without nuance. Exposition found in action sequences and narrative descriptions often serves as a soundboard for Howard’s opinionated musings. In “The Tower of the Elephant,” the esoteric author weaves commentary seamlessly with the story’s movement. Could a Marvel Comics’ team effectively translate Howard’s quirky approach to the comic book medium?

Thomas and Windsor-Smith’s challenge involved slimming down the prose while retaining the story’s impact. When limited to panel artwork, caption boxes, and word balloons, fitting the bulk of Howard’s commentary becomes next to impossible. Thomas and Windsor-Smith seem to do the impossible. They retained the original short story’s magazine prose “spirit” through using the “Marvel method” of allowing the art to tell the tale and then supporting the visuals with appropriate dialogue and descriptive text. Sometimes, the best adaptations come from creators who know what to cut to allow a workable transition to a new medium.

Fleshing Out the Tale in Comic Book Form

Had Thomas and Smith stuck with merely retelling the basic plot and action, they’d still have a terrific tale. “The Tower of the Elephant” puts forth an excellent mystery story with some incredible twists, such as Conan’s discovery that the tower’s “elephant” is a strange humanoid space alien. And the surprise continues when Conan and the reader learn the “monster” is a kind, decent, and tragic figure.

The tale commences when an inquisitive Conan approaches a slaver and asks about the mysterious “tower of the elephant,” the wizard Yara’s abode. The barbarian hears magnificent jewels are inside the top story of the tower, and he can’t understand why no one has yet stolen them.

And what does the tower have to do with elephants, mysterious creatures not indigenous to this part of the world?

In the comic, things progress quickly throughout several panels. We know a “Kothian rogue” is a slave trader, so he is established as a villain. Conan still approaches respectfully when asking about plans for stealing the jewels. When Conan mentions everyone’s misgivings about the impossible task of sneaking into the elephant’s tower, he throws around the word “cowardice.” Doing so enrages everyone in the tavern leading to Conan killing the slaver and other rogues.

The scene plays out longer in Howard’s short story. Conan receives much less dignity from these men because they mark him for being young and stupid; at least this is how they see him. By getting into the head of Conan, Howard establishes how the then 17-year-old sees these surly men. He thinks to himself, “Civilized men are more discourteous than savages because they know they can be impolite without having their skull split, as a general thing.” Of course, this musing is the rampant cynicism of Robert E. Howard in print. Regardless, this understanding leads Conan to look the other way when the slaver refers to him as a “barbarian.”

He doesn’t look away for long. After slaying men in the tavern, Conan goes on his way to the mysterious tower.

Howard, Conan, and Yag-Kosha by Way of Comic Book Art and Storytelling

The abbreviated version of the comic book effectively presents Conan’s adventure visually. While not as expository as the short story, the comic book version tells the tale while allowing the reader to gain insights into Conan and, indirectly, Robert E. Howard.

After a few establishing pages, Conan makes his journey to the tower, and he kills men and strange beasts along the way. Upon reaching the top of the tower, he realizes why it gets its mysterious name: a creature who appears half-elephant/half-human lives there. The being is not Yara’s guest, but a tortured prisoner. And he has a name, Yag-kosha.

In a tribute to Howard’s prose, the revelation of Yag-kosha brilliantly shifts from mystery and foreboding to melancholy, sadness, in only a handful of panels. As Conan first nears Yag-kosha, Windsor-Smith’s art depicts the creature as somewhat evil and menacing. The tense menace increases in the panel where the creature’s eyes open, leaving the reader to wonder about a confrontation with Conan. The art displays a Conan who seems unusually fearful, further adding mystery to where the tale is going. Things quickly shift as the alien reveals his unfortunate plight. Yag-kosha is the blinded, pitiful prisoner of Yara.

The issue’s artwork captures the alienation that bleeds from Howard’s writing. Rather than appear the expected “elephant grey,” Yag-kosha is greenish, which highlights his otherworldliness. The look supports his alien origins and also creates a stark contrast to earth creatures.

Choosing green for the color of Yag-kosha’s word balloons and descriptive boxes continues the brilliant touch to separate him from other characters in the comic and, in turn, humanity. And green was not chosen randomly. In Howard’s story, Yag-kosha continually refers to his “green” homeland. The panels also reveal the alien first arrived on earth thousands of years earlier when the world was young, and, yes, green.

So, it is wrong to refer to Yag-kosha as “otherworldly.” He fit quite well into a young earth’s environment, where the once-flying creature sheds his wings to remain on the new land. But he would eventually become the captive of an evil man who took to torturing Yag-kosha to learn the alien’s magical secrets of wizardry. The “human” Yara, in comparison to the alien Yag-kosha and the barbarian Conan, is the most inhuman and uncivilized of all.

Thomas and Windsor-Smith move very quickly to get these thematic and character points about Yag-kosha across, and since they were not writing for a magazine or an annual, they had no choice. Yet, much of Howard’s original sentiment remains in the issue.

Readers discover insights into the sentiment through a powerful line from the story. In “The Tower of the Elephant,” Howard reveals Conan’s emotional turmoil when the character feels “as if the guilt of a whole race were laid upon him” upon discovering the sad plight and contributing to the final fate of Yag-kosha. Conan feels embarrassed for humanity due to its treatment of the visitor from another world Roy Thomas shrewdly retained these words in a descriptive panel box. The prose’s inclusion establishes Conan’s depth, a character mistakenly noted for being “one-note.” The quote also reveals a bit about Howard’s psyche, a writer sometimes inseparable from his characters.

A powerful aspect of the story then carries over into the comic book version.

Howard on Howard, Indirectly

Beyond Conan, there seems to be a touch of Howard in Yag-kosha, as well. Howard could not connect with others in his Texas life; he may have felt otherworldly and imprisoned as Yag-kosha.

Yag-kosha personifies Howard, a talented visionary with unique skills. Yag-kosha flew through outer space with his wings from his home planet to a mysterious new home, as Howard escaped boredom and misery through his writings. And now, both the character and creator feel trapped and disconnected on earth. Howard’s relationship with others and his environment was not as brutal as the one between Yag-kosha and Yara. However, the two fictitious characters might reflect an exaggerated version of Howard’s sentiments.

Again, limitations on both page and panel quantities do not allow Thomas and Smith to delve too deeply into Yag-kosha’s thematics. Yet, a brilliantly drawn panel featuring a then-winged Yag-kosha flying through outer space shows his majestic abilities gloriously. The single panel has an ultra 1970s gaudy sci-fi style, and it works immensely well. Readers see Yag-kosha comes from a beautiful place, geographically and metaphorically “above” our world, and the readers feel pain for his plight.

While the artwork does not spell out sentimentality to the degree Howard’s writing does, the visual impact gets the content and impact across. The panel where Windsor-Smith’s art depicts the flying elephants losing their wings parades Howard’s prose’s emotion in a visually striking manner. Therein lies the brilliance of sequential art storytelling: allowing the prose and artwork to convey great emotional and narrative content in a “confined space.”

The Legacy of Yag-kosha’s Story

Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith masterfully transferred one of Robert E. Howard’s best works to a vastly different storytelling medium. The two comic creators’ brilliance shines in their ability to take key points from a somewhat lengthy short story, present the tale with brevity, and drive those main points home both textually and visually to ensure the spirit of Howard’s “The Tower of the Elephant” remains.

It took many decades for Howard’s reputation to rise above the description of a disposable pulp writer. The same truth applies to scores of outstanding Golden, Silver, and Bronze Age comic book creators. And the truth comes through one story at a time, as brilliant works from decades ago experience rediscovery.

Anthony Caro writes about all things pop culture and contributed to HorrorNews.Net, PopMatters, Mad Scientist, Jiu-Jitsu Times, and more. Besides working as a professional ghostwriter, he handled production duties in radio, TV, film, and theater.

essay ©2023 Anthony Caro

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out our CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.

Images used ©Their Respective Copyright Holders