Max Fleischer (1883–1972): Inventor, Cartoonist, Animation Pioneer By Matthew Rizzuto

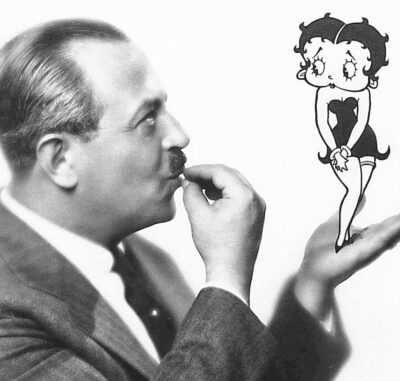

Max Fleischer was an animator, director and inventor of some 30 patents for animation production. He is best known for creating animated cartoons featuring popular characters including Betty Boop, Popeye The Sailor, Koko The Clown and Superman. He is considered one the three major pioneers of American animation of the 20th Century, along with Winsor McCay and Walt Disney.

Max Fleischer (born Majer Fleischer) was a Polish-American animator, inventor, film director and producer.

Fleischer became a pioneer in the development of the animated cartoon and served as the head of Fleischer Studios, which he co-founded with his younger brother Dave, in the United States of America.

He brought such animated characters as Koko The Clown, Betty Boop, Popeye and Superman to the movie screen and was responsible for a number of technological innovations, including the Rotoscope, the “Bouncing Ball” song films and the “Stereoptical Process”. Max Fleischer’s son was noted film director, Richard O. Fleischer.

Max Fleischer was born on July 18, 1883, in Kraków, Poland in the province of Galicia under the Austro-Hungarian Empire to a Jewish family in Kraków, then part of the Austrian-Hungarian province of Austrian Poland. He was the second of six children of a tailor from Dąbrowa Tarnowska, Aaron Fleischer, who later changed his name to William in the United States and Malka “Amelia” Palasz.

His family emigrated to the United States of America in March 1887, settling in New York City when Fleischer was five years old. It was there that he attended public school. During his early formative years, he enjoyed a middle class lifestyle, the result of his father’s success as an exclusive tailor to high society clients.

This changed drastically after his father lost his business ten years later. His teens were spent in Brownsville, a poor Jewish ghetto in Brooklyn, New York.

Not long after that, Fleischer attended public school and after graduating from Evening High School, he attended The Mechanics and Tradesman School, The Art Students League and Cooper Union, where he received a commercial art degree.

His career began at The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, where he worked his way up from running errands to the positions of photographer and staff cartoonist while still in his teens. He began drawing single panel political cartoons for “fillers” and later drew two daily comic strips, Little Algy and E.K. Sposher, The Camera Fiend.

In 1905, while at The Eagle, Fleischer became well acquainted with illustrator/cartoonist, John R. Bray, who recommended him for a technical illustrator job for The Electro-Light Engraving Company in Boston.

On Christmas Eve that year, Max married his childhood sweetheart, Ethel Goldstein. A year later their daughter, Ruth, was born. Their son Richard was born in 1916.

In 1909, Max and his family moved to Syracuse, New York, where he was a catalog illustrator for the Crouse-Hinds Company. A year later, he moved back to New York and became art editor for Popular Science Magazine.

It was during this period that Max became involved in animation at the suggestion of his boss, Waldemar Klaempffert.

Having seen a crudely produced animated cartoon at a movie the previous evening, he suggested that Max find a way of improving animation through the application of photography and mechanics.

By 1914, the first commercially produced animated cartoons started to appear in movie theaters. They tended to be stiff and jerky. Fleischer devised an improvement in animation through a combined projector and easel for tracing images from live action film.

This device, known as the Rotoscope, a combination of a film projector and easel, designed to trace figures from motion picture footage to produce fluid, realistic animation, enabled Fleischer to produce the first realistic animation since the initial works of Winsor McCay.

Although his patent was granted in 1917, Max and his brothers Joe and Dave Fleischer, made their first series of tests between 1914 and 1916.

After two experiments, he filmed his younger brother, Dave in his Coney Island clown costume for an original subject.

The result led to his being hired by John R. Bray as production manager and producer of a series of monthly releases titled, “Out of The Inkwell”.

The first releases (1918-1921) were produced at the pioneering Bray Studios, included in the Bray-Goldwyn Pictograph film magazine series.

The series was popular with movie audiences due to its clever combinations of animation with live action, showing Fleischer drawing the clown and interacting with him.

The climax of each film would involve the animated character “crossing the fourth wall” and pulling some prank or act of revenge in the real world.

In addition to entertainment novelty series such as “Out of The Inkwell”, Fleischer produced several educational films during the silent era, beginning with a series for the U.S. Army during World War I on subjects including, “Contour Map Reading” and “Firing The Stokes Mortar”. Fleischer also produced a number of films on astronomy, including “All Aboard For The Moon” and “Hello, Mars”.

Max Fleischer formed Out of The Inkwell Films, Inc. with his brother, Dave in 1921 and continued with technical advancements, including the Rotograph technique, an early optical process that allowed for the re-photographing of live action film footage with animation cels.

His invention was the precursor to the aerial image process used widely in the 1960’s and 1970’s for compositing titles over live action background footage.

In 1924, Fleischer invented the “bouncing ball” sing-along films, first known as Song Car-tunes and later Screen Songs.

Several of the early Song Car-tunes were released with soundtracks between 1926 and 1927, prior to the official start of the “talkie era” and preceding Walt Disney’s Steamboat Willie as the first sound cartoon by two years.

It was in this period that the “Fleischer Clown” became known as “Ko-Ko The Clown” (Koko The Clown).

In 1923, Fleischer produced two important 20 minute science films, “Evolution” and “Relativity”, both using live action and animation special effects to demonstrate these theories.

With talking motion pictures taking hold by 1929, Fleischer had a secure financial/distribution arrangement with Paramount Pictures and its large network of theaters.

Then, in 1930, Fleischer found great success in what started as a cameo character, who transformed very quickly into its most successful character at that time, Betty Boop.

In 1934, popular singer, Helen Kane sued Fleischer and Paramount over the Betty Boop character, only to lose when it was proven that Kane had stolen the singing style from an African-American performer, “Baby” Esther Jones.

Fleischer’s greatest business move came with securing the screen rights to the famous Elzie Crisler Segar comic strip character, Popeye The Sailor. It was Max Fleischer’s idea to take comic strip characters and make cartoons out of them.

The huge success of the Popeye series propelled Fleischer’s studio into unheralded success and the continued demand for “Popeye” cartoons led to a major labor strike in 1937.

Fleischer was at the zenith of his career with his most impressive technical development in the Stereoptical Process shown to great affect in The Color Classics series and most importantly in the two-reel Popeye specials — “Popeye The Sailor Meets Sindbad The Sailor” (1936) and “Popeye The Sailor Meets Ali Baba and His Forty Thieves” (1937).

Following the settlement of the strike, Fleischer announced plans to relocate to Miami, Florida with a new production schedule of short subjects and features.

Fleischer’s gradual move toward longer animated films paved the way for animated features, allowing for the success of Walt Disney’s “Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs”, Paramount backed Fleischer on his first full-length feature, Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” (1939).

Fleischer’s next major business move was with National Allied Publications (today DC Comics) and the Superman screen rights, which propelled his studio into relevance in the 1940’s with its science fiction fantasy content.

While Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman was an instant hit, for the Fleischers, it came too late.

The working relationship between Max and Dave Fleischer had deteriorated during the production of “Gulliver’s Travels” and Fleischer’s organization came under reorganization following Paramount’s losses over their final feature, “Mr. Bug Goes To Town” (1941).

While set for release as Paramount’s 1941 Christmas film, “Mr. Bug” was plagued with problems. It was rejected by theater operators and its release was further complicated by the national panic set off by the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Due to continued losses, Max Fleischer resigned and Fleischer Studios reorganized as Famous Studios on May 27, 1942.

Later on in 1943, Fleischer was involved with top secret research and development for the war effort, including an aircraft bomber sighting system.

In 1944, he published “Noah’s Shoes”, a metaphoric account of the building and loss of his studio, casting himself as Noah.

Soon after that, Fleischer parlayed his experience producing educational and industrial films into a new position as head of the animation department at The Jam Handy Organization, which required him to move to Detroit, Michigan, where he remained until 1956.

His career came full circle as he returned to The Bray Studio as production manager and developed pilots for educational television series, including “Imagine That!”.

Following World War II, he supervised the production of the animated adaptation of “Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer” (1948), sponsored by Montgomery Ward.

Fleischer left Handy in 1953 and returned as production manager for the Bray Studios in New York, where he developed an educational television pilot about unusual birds and animals titled, “Imagine That!”

In 1954, Max’s son, Richard Fleischer was directing the Academy Award-winning, “20,000 Leagues Under The Sea” for Walt Disney.

This brought about the honorary luncheon that united Max with his former competitor and reunited him with a number of former Fleischer animators who were then employed by Disney.

It was at this meeting of the former rivals seemed cordial, and Max remarked that he was very happy making educational films at this point in his career.

However, in his collection of memoirs entitled, “Just Tell Me When To Cry”, Richard relates how, at the mere mention of Disney’s name, Max would mutter, “that son of a bitch”.

In 1956, Fleischer sued Paramount for $2,750,000 over the sale of the cartoons produced under his contracts and won the lawsuit.

By 1958, he resurrected his old company, Out of The Inkwell Films, Inc. to bring Koko The Clown to television and in 1960, 100 new color cartoons were produced by Fleischer’s former animator, Hal Seeger.

After years of battling with Paramount, Fleischer’s health began to deteriorate. During that time, he fought to regain the title to Betty Boop, a battle he eventually won by the time of his death.

When Fleischer died on September 11, 1972 from arterial sclerosis of the brain, Time Magazine referred to him as “Dean of Animated Cartoons”, a title most deserving of Fleischer.

Fleischer’s son Richard O. Fleischer, an Academy Award-winning film director for Best Documentary Feature “Design For Death” (1947) and acclaimed motion picture director for such hit films as “Barabbas” (1962), “20,000 Leagues Under The Sea” (1954), “Red Sonja” (1985), “Doctor Dolittle” (1967), “Soylent Green” (1973), “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (1970), “Fantastic Voyage” (1966), “Conan The Destroyer” (1984), wrote “Out of The Inkwell: Max Fleischer and The Animation Revolution” (University Press of Kentucky), a biography about his father which was released in 2005.

Just so everyone knows, “The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer” (McFarland, 2016) by Ray Pointer also covers the Fleischer’s life and pioneering work.

If anything, Max Fleischer was an unparalleled genius and his dedication to animation was absolutely amazing.

Thank You.

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out our CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Photos and images ©Their Respective Copyright holders, Superman ©DC Comics

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.