Advancement of Storytelling and Legal Lessons in Platinum Age comic strips by Alex Grand

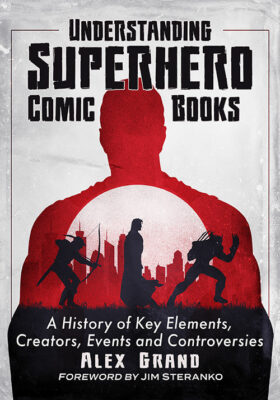

Read Alex Grand’s Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland Books in 2023 with Foreword by Jim Steranko with editorial reviews by comic book professionals, Jim Shooter, Tom Palmer, Tom DeFalco, Danny Fingeroth, Alex Segura, Carl Potts, Guy Dorian Sr. and more.

In the meantime enjoy the show:

We all love comic books, to the point where most of us spend money to read them. We love their creativity, their form, their pictures, their words, but they weren’t always there. The form came from somewhere. Technically sequential visual stories go back to Egyptian Hieroglyphics, but there is a picture story book format that begins in the 1800s that we can call comics, and its important to trace how they influenced the form and foundational structure of today’s comic book storytelling. So just to put it out there now, America’s comic storytelling has its origins in Europe.

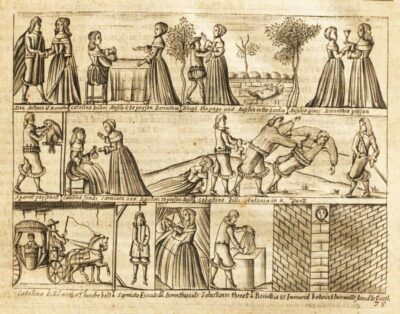

First we have “God’s Revenge for Murder” by John Reynolds in 1656, first one seen in the English language.

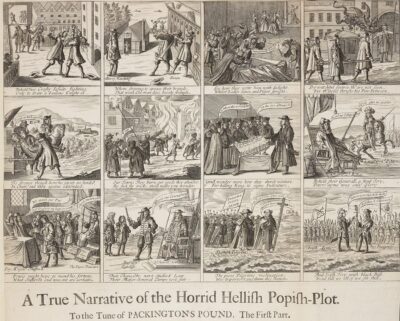

But dialogue balloons would start with the Yellow Kid right? Wrong! We see dialogue balloons pop up in “A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish Plot” by Francis Barlow in 1682 about Titus Oates eventual arrest.

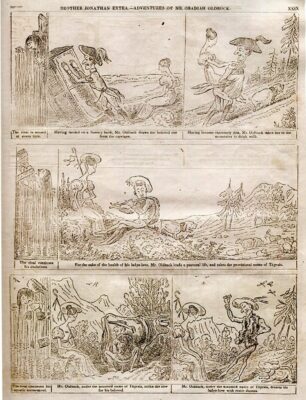

Let’s fast forward a bit to 1827 when Swiss writer-artist, Rodolphe Topffer produced multipaneled sequential art well before the Yellow Kid as early as 1827. These were originally in French, and this was reprinted in a Brother Jonathan Extra as a 40 page comic book in the United States known as the Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck which was produced in New York City. Check out an interior page, there are captions with sequential action and reaction which makes it more like a comic book than the previous stories.

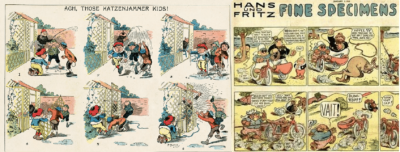

The comic art form became a fascinating new tool in Germany in the 1860s with Wilhelm Busch’s mischief comic, Max und Moritz, a comic that stayed in Germany but influenced Rudolph Dirks, who immigrated to the United States and created Katzenjammer Kids in 1897 which concerned the adventures of Hans and Fritz, again in New York City.

Rudolph Dirks worked for 15 years on Katzenjammer Kids and according to his son in Cartoonist Profiles 1974, Rudolph wanted to leave Hearst for Pulitzer’s New York World. Court case final decision said that old man Rudy could draw his original characters for a different title for the New York World, but Hearst’s Journal would still own the original title, so Hearst hired Knerr to continue Katzenjammer Kids in 1914 and Dirks renamed his feature Hans und Fritz, changing to Captain and the Kids during WW1 and the competing strips continued.

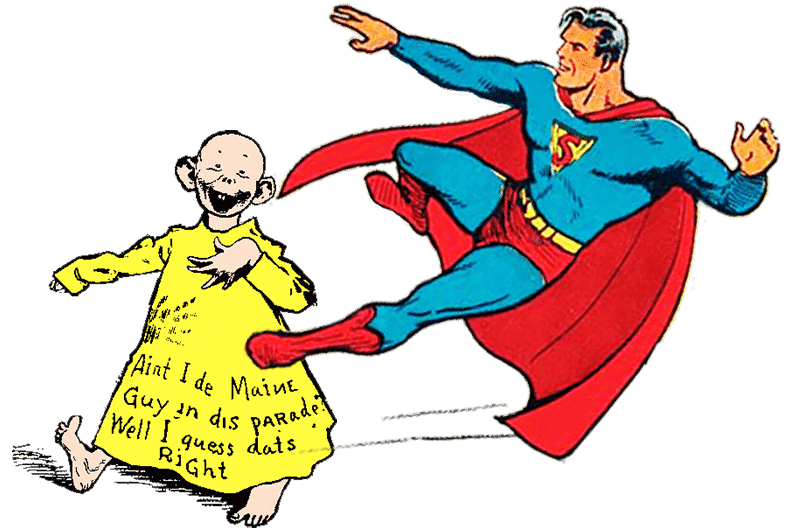

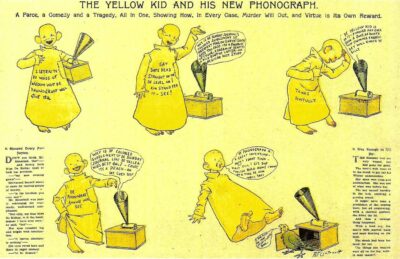

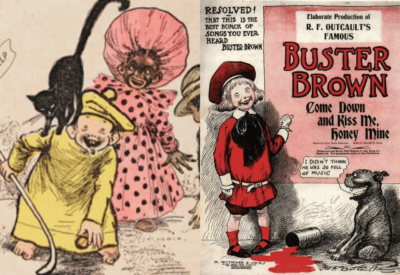

However someone in the United States would beat Rudolph Dirks to the comic strip race, and that was Ohio-born R.F. Outcault who worked on cartoons for the New York World, which had started publishing them in 1889. He created the Mickey Dugan character in 1895 in Hogan’s Alley, but in 1896, Hearst owned New York Journal and hired Pulitzer’s publisher the same year. Hearst got a high speed multicolor press and hired Outcault around the same time who continued Mickey Dugan’s adventures as the Yellow Kid. Outcault made a special sequential interaction between the Yellow Kid and a Parrot with speech balloons that mimic the cadence of a discussion followed by the reader. Some feel that changed comics to a post-Outcault period that birthed the 20th century comic right at the end of the 19th century. Not because it was a new technique, it actually already was a few hundred years old by this time, but the character, format, cheap method to print many copies to package and sell to millions, with fast presses opened up a new age of Comic Strips because it made a lot of money, and other me-too (not #metoo) characters and artists joined in on the trend to make similar or more money. Ages can be defined with what new trend makes a lot of money. That upsurge of cash starts off this newspaper comic strip age in the United States and the race was on to find similar appealing entertaining characters and their comic book reprints, and this is the beginning of the Platinum Age of Comics.

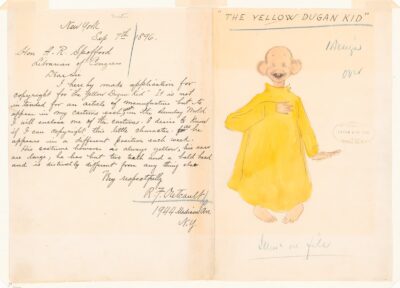

As far as early legal lessons, in September 1896 Outcault applied for copyright registration by sending a letter with The Yellow Kid to the Library of Congress which wasn’t granted and competing Yellow Kid imagery continued between Pulitzer’s World and Hearst’s Journal and so since Outcault didn’t own the character, he lost interest and left the strip in 1898.

Technically, the first newspaper should have copyrighted the character, which never happened creating brand confusion in the newspaper comic marketplace! So Outcault left the Yellow Kid character and created Buster Brown in 1902 for James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald. Outcault left the Herald Newspaper later, and Bennett’s people hired an artist thought by the public to be inferior, and the newspaper found no apparent drop in sales! This began a trend in comics where the character was actually worth more than the creator, which was a critically important lesson learned by publishers. A similar feud as occurred like the Yellow Kid where Outcault continued the character for Hearst’s paper and both papers were legally granted the right to use the character, but both papers had to use different names, however Outcault was awarded ANCILLARY rights which means George Lucas style merchandising rights and he ended up making more money off the merchandising, than from the actual comic book. Outcault licensed his character’s brand name to a Shoe company, watch manufacturer, dolls, toys, games, coffee, bread, etc., and this was the first comic character to do that which is another milestone big deal.

Let’s slip one in on the timeline between Yellow Kid and Buster Brown with the unlucky hobo character, Happy Hooligan by Frederick Burr Opper created in 1900 for the New York American which was a Hearst newspaper also known as King Feature Syndicate.

Something notable about Happy Hooligan was that it was given a movie by the Thomas Edison Film Company and its the earliest example of when film and comics synergized for a corporate brand. This can be considered a precursor to Avengers Endgame!

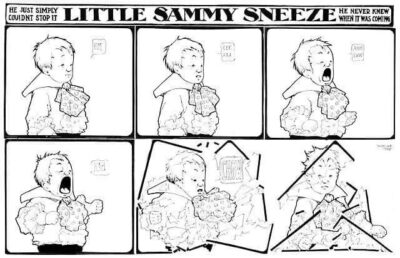

The next strip artist who elevated the form and pioneered more comic lessons was Winsor McCay who was an incredibly fast draftsman & made 3 strips at once including his Little Nemo for James Gordon Bennett’s New York herald from 1905 to 1911 before moving to William Randolph Hearst’s periodical, the American. His usage of comic illustration and satire of the form itself was ingenious for his time, like this example where he breaks the fourth wall in the Sammy Sneeze newspaper strip in 1905 in a style that befits Deadpool.

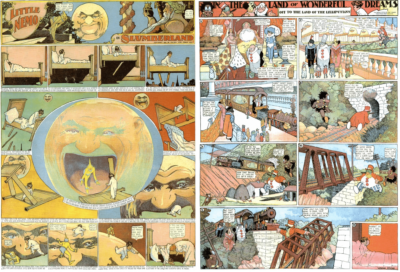

Some legal background on McCay’s Little Nemo, Little Nemo in Slumberland debuted in Bennett’s New York Herald in 1905 and lasted there until 1911. In 1911, Winsor was hired by Hearst for his competing newspaper. The Herald held the strip’s copyright,but McCay won a lawsuit that allowed him to continue using the characters, and continued his character as new title, In the Land of Wonderful Dreams.

This is a similar happenstance as Outcault and Buster Brown, however in this case the Herald did not find a replacement artist that could substitute for McCay because he was so good, so in this case, the artist superstar is essentially born in comics. McCay was so good that he also came up with another valuable lesson that modern comics would enjoy, and that was his pioneering in animation to create another corporate synergy product, the cartoon based on the comic! Check out this link here for his Little Nemo cartoon from 1911.

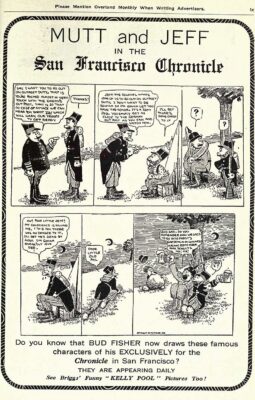

In 1907, Bud Fisher created A. Mutt, a character designed to gamble and play the races, but Fisher developed it into a comic strip that had a comedic recurring character which was the first to show up in a popular horizontal daily format first showing up in the San Francisco Chronicle. He was also the first comic artist to copyright his character in his strip without the newspaper knowing, making it his legal property! Hearst was evidently so impressed with Bud Fisher’s work, that he offered him work away from the competing paper to his San Francisco Examiner, however Bud Fisher wrote “Copyright 1907 H.C. Fisher” in the last strip he submitted to the Chronicle and the first two he drew for the Examiner.

He then registered the copyright in Washington, D.C, which paid off tremendously. The SF Chronicle tried to replace him on their A. Mutt and Fisher challenged them legally, and so in 1908 the Chronicle caved and ceased publishing A.Mutt and Fisher was established as the full owner of the strip which graduated into becoming Mutt and Jeff after developing fictional costar. It turned out that the “odd couple” set up for situational humor worked well and this would affect both strips, TV and films for years to come.

Fisher’s full ownership of the copyright was a lesson to everyone and he signed a 5 year contract with Hearst. Later though, Fisher signed a more lucrative deal with the Wheeler Syndicate and decided to leave the soon to be furious Hearst. The wiley Hearst tried to copyright the title Mutt and Jeff last minute and he sought an injunction to prevent the Wheeler Syndicate from using the title and characters. Wheeler started two lawsuits to prevent Hearst from producing imitations and the judges involved ruled in favor of Fisher in all three lawsuits. Hearst, stubborn as always, took this issue to the U.S. Supreme Court which in 1921 refused to overrule the lower courts granting a landmark decision in comic history giving the very proud Bud Fisher complete ownership over the characters, title, film rights, merchandising rights and a share in the profits of his own strip wherever it was printed. The concept that copyright equals money was critically important and made comic publishers very aware of this basic fact making it much more difficult to do what Fisher did, however the basic concept was very much present in the 1990s Image Revolution where creator owned copyrights made kings and queens in the industry.

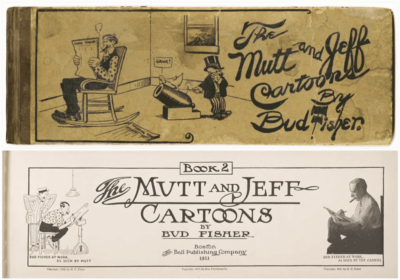

There are reports of a Yellow Kid reprint comic book from 1897, however it is important to note that Steranko writes in his history of comics volume 1, 1970 that the “first comic book” was this 18″ wide X 6″ high Mutt and Jeff Cartoons in 1911 from a Chicago newspaper which was very successful showing that reprint comic books were a financially viable option and format.

In 1919, Bud Fisher actually depicts himself in his own strip interacting with his characters much like writers and artists like Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and John Byrne would do in later comic books. In this example, Bud Fisher showed in a Mutt and Jeff Comic Daily news strip that there is no way to please all comic readers which is an early reference to chronically unhappy fandom! This is another precursor to modern times!

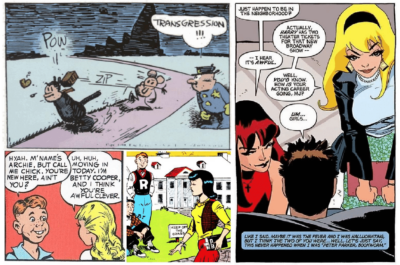

After Bud Fisher, we start entering the time frame of 1910s to 1940s with the newspaper comic strip, Krazy Kat by George Herriman who gave a hook to readers when he eventually introduced the love triangle. Krazy Kat, the title character, loved Ignatz the Mouse who didn’t love the Kat back. Officer Bull Pupp loved the Kat, who was focused on the mouse. The eternal unsatisfied resolution of tension is something that works in comics. MLJ’s Pep Comics in the 1940s did the same once Veronica was later added to the mix a few issues later, as the title character was loved by Betty, but he loved Veronica who only loved herself. Stan Lee and John Romita create this situation with Spider-Man and his run ins with with Gwen Stacy and Mary Jane that added more sales to the monthly title, and this was re-illustrated by Tim Sale much later.

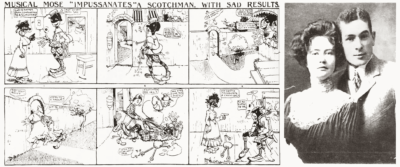

Let’s expand more on George Herriman of the Krazy Kat, who was the son of parents with partial African ancestry. When he was born in 1880, his birth certificate said colored. He was light skinned enough to shmooze with the predominantly Caucasian newspaper crowd at the time starting in 1897 working on comics. His fellow artists thought him Greek due to his black curly hair, and he was able to mix into the crowd and earn himself a success with his artistry. Before Krazy Kat, he ironically made a strip in 1902 called Musical Mose about a Black man in typical (and very unfortunate) Black face who tried unsuccessfully to pass himself off as White. This makes for a closeup look of how much work had to be done for African American equality, as well as the constant struggle of the lighter skinned mixed people of the time ingratiating into society by denying their racial heritage. Here is also a picture of Herriman from the same year as this newspaper strip with his new bride, Mabel.

Similar to Art Spiegelman’s Maus 1986, George Herriman would introduce some thought provoking topics in his Krazy Kat strip even as far back as 1915, shown in this daily discussing sexuality. Almost like Dr. Seuss’ 1957 Cat in the Hat, there is a whimsical approach that doesn’t dig too deep, but gives a subtle jab at an eternal question.

As fun as it is watching Deadpool or Sammy Sneeze break the 4th wall in the comics, George Herriman had his Krazy Kat character doing the same as far back as 1915 shown here with an inkblot overcoming the panel.

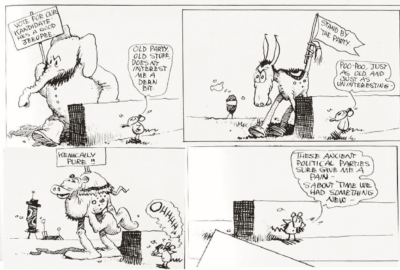

Another storytelling trope that would be used in later comics was political commentary. In 1920, the USA Presidential Election was the first election after WW1. Republican Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding defeated Democratic Ohio Governor James M. Cox of Ohio. George Herriman demonstrates Political Party fatigue that year in a Krazy Kat Sunday.

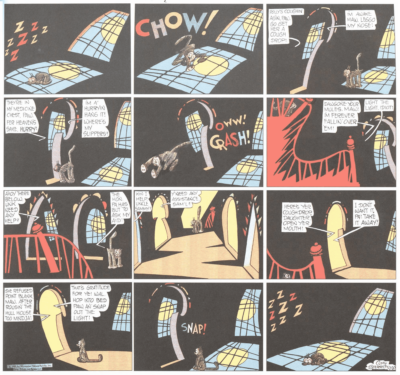

The next newspaper comic strip that really elevated comic storytelling and pioneered later used tropes was Cliff Sterrett who penciled and wrote Polly and her Pals Newspaper strip for the majority of the first half of the 20th century starting in 1912. Roughly in the mid 1920s, the art went from lively family situational comedy to surreal art experiments and expressions that visually took a life of its own. This Sunday is from 1927, actually showing night time in Polly’s family’s house from their cat’s perspective utilizing some abstract imagery which seems to express something along the lines of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, with an almost Dr. Strange type window in the background.

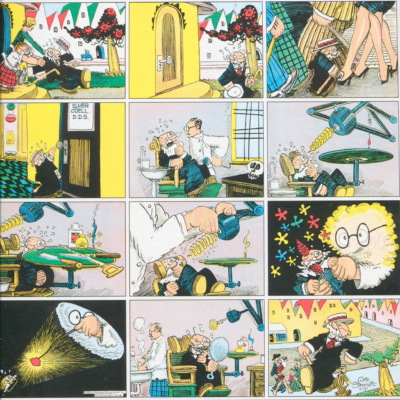

Going further into the Dr. Strange aesthetic is depicting emotions in an astral fashion. Not exactly astral projection, but he is able to put human emotions into an astral projection form in his Sundays. Here is one from 1928 where Polly’s Pa is going through his dental appointment, and the surreal depiction of his fears and psychological dissociation during the in office procedure are just priceless.

These astral emotions are used with some great dreamland techniques that Cliff Sterrett puts into his stories. Here is one segment from 1928 of Polly’s Pa entering dreamland and encountering his own personal insecurity with his daughter’s boyfriend. It is the metaphysical aspect that is interesting, and later iterations of dreamland or astral plane or nightmare world are just as fascinating in later comics like Dr. Strange or The Sandman.

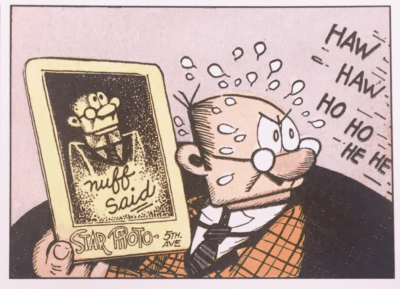

Polly and Her Pal’s also shows an example where Newspaper Comic strips were using the phrase “Nuff Said” to end and act as a punchline to a visual sequential narrative years before comic books like those by the notable Stan Lee. Here’s an example from Cliff Sterrett’s Polly and her Pals 1930 which segue’s into the 1930s precursors set by in other episodes.

It’s important to note that alot of the comic story telling, even the importance of owning a reoccurring character, the monetization and merchandising of that character, film rights, corporate synergy, and buzz words were all pioneered by the early comic strip creators, and that modern comic books stand on the shoulders of these giants.

cheers.

Join us for more discussion at our Facebook group

check out our CBH documentary videos on our CBH Youtube Channel

get some historic comic book shirts, pillows, etc at CBH Merchandise

check out our CBH Podcast available on Apple Podcasts, Google PlayerFM and Stitcher.

Use of images are not intended to infringe on copyright, but merely used for academic purpose.

katzenjammer kids © KFS, Polly and her Pals ©Library of American Comics, Krazy Kat ©KFS