Paul Levitz Interview: DC Comics Fan, Writer, Editor, Publisher, President by Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

Read Alex Grand’s Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland Books in 2023 with Foreword by Jim Steranko with editorial reviews by comic book professionals, Jim Shooter, Tom Palmer, Tom DeFalco, Danny Fingeroth, Alex Segura, Carl Potts, Guy Dorian Sr. and more.

In the meantime enjoy the show:

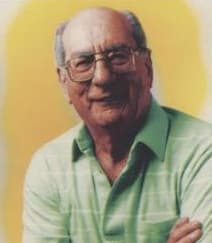

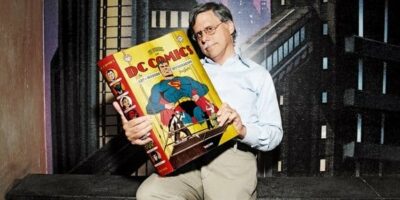

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview Paul Levitz. Paul Levitz is an American comic book writer, editor and executive. The president of DC Comics from 2002–2009, he

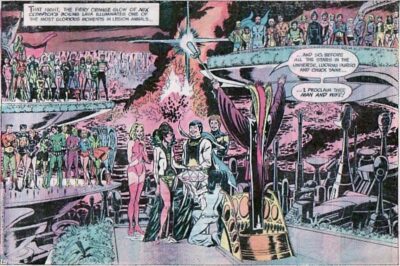

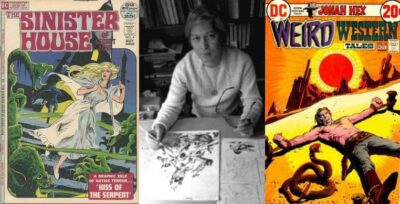

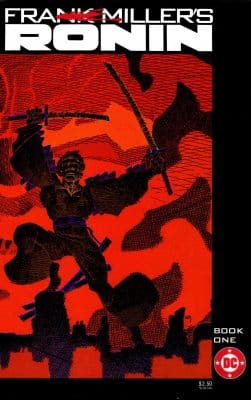

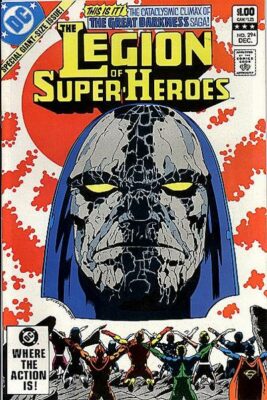

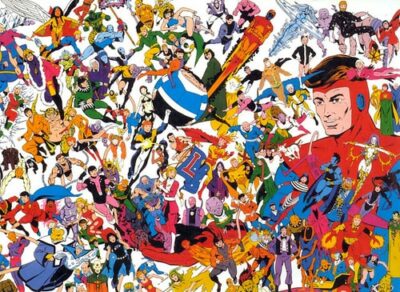

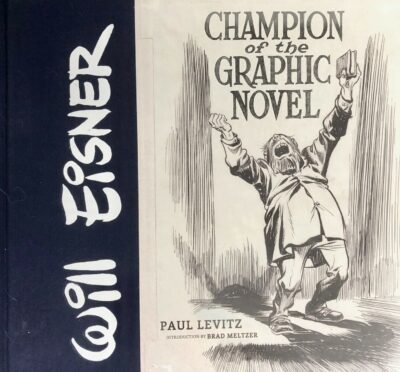

worked for the company for over 35 years in a wide variety of roles. At DC Comics, started in the Fanzines in 1971, assistant to Joe Orlando, working under Carmine Infantino then Jenette Kahn as Publisher, and Freelance writer, to full time Editor and writer in 1976, working on All Star Comics with Wally Wood, Stalker with Steve Ditko, and promotion to upper management, writing and editing Batman in 1978, working with Julius Schwartz, Vice President in the 1980s with a lengthy run on the Legion of Superheroes and co-creating many characters like Huntress, the changes in the 1980s that he and Jenette Kahn brought to DC Comics, Jim Shooter’s effect on both companies, the payment of royalties to artists and creators, publishing Will Eisner’s work, the effect of the DC Movies on DC Comic’s corporate identity, growth of the Direct Market, hiring Frank Miller, John Byrne, Alan Moore, Karen Berger’s Vertigo, his role as President and his new project for Valiant Comics, The Visitor.

🎬 Edited & Produced by Alex Grand, ©2021 Comic Book Historians Sound FX – Standard License. Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders. Images used for academic purposes only.

Paul Levitz Biographical Interview 2019 by Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

📜 Video chapters

00:00:00 Welcoming Paul Levitz

00:00:29 Family background

00:01:42 Reading comics

00:04:29 Mort Weisinger – Superman, Legion of Superheroes

00:06:16 Reading Marvel comics

00:07:27 Steve Ditko

00:08:08 Proto fanzines

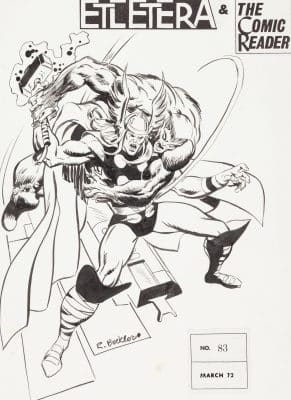

00:09:18 Etcetera, a news magazine ~1971 | Paul Kupperberg

00:10:58 What a fan meant, back in ’71?

00:13:33 Legion fandoms

00:15:21 Jack Kirby to DC, New Gods | Carol Fein

00:16:53 …weren’t really focused on mythology

00:20:27 The Comic Reader

00:22:01 Etcetera and The Comic Reader | Paul Kupperberg

00:24:14 Attract artists to work on the covers?

00:25:59 Tom Fagan

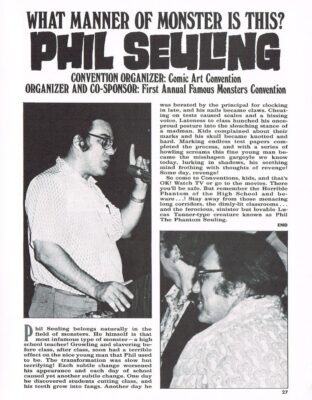

00:26:20 Phil Seuling, program book for 1973 Comic Art Convention

00:28:34 Sold TCR in 1973 to Street Enterprises

00:29:46 Freelance work at DC

00:31:38 Assistant editor under Joe Orlando

00:33:18 Gerry Conway

00:35:36 DC environment at that time

00:37:52 Siegel and Shuster lawsuit ~1975

00:40:02 Neal Adams, Dick Giordano – Continuity

00:40:50 Carmine Infantino

00:44:24 Stalker | Working with Steve Ditko, Wally Wood

00:45:44 Conan, Sword-and-sorcery

00:46:26 Lucien the Librarian, Tales of Ghost Castle ~1975

00:47:32 Weird Mystery Tales

00:49:54 Filipinos on mystery and war books

00:53:18 Negative older artists’ negotiations

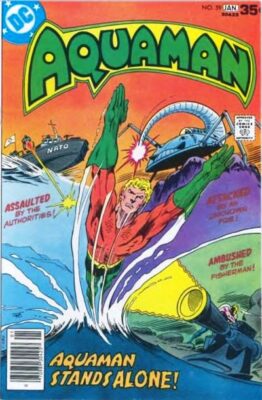

00:54:21 Aquaman | Aparo

00:56:04 Learn to be a better writer?

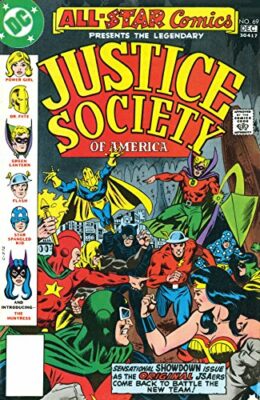

00:58:27 All-Star Comics ~1976

01:00:07 Bringing Wally Wood to DC

01:05:07 Favorite characters,

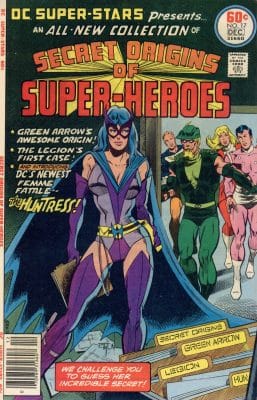

01:06:24 Huntress, co-creation Staton and Layton

01:07:10 Earth-2

01:08:29 Legion of Superheroes

01:10:40 Karate Kid

01:12:20 Full-time editor and writer ~1976 | There is hope now

01:18:42 Jenette Kahn

01:20:53 Writing drafts of contracts | Bob Stein

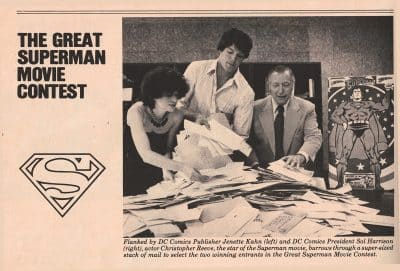

01:23:01 Sol Harrison president, Jenette Kahn as the publisher

01:28:08 Editor of Batman comics

01:29:58 Julius Schwartz

01:32:21 Industry changes in the late 70s | Jim Shooter

01:38:03 Multiple title changes

01:41:38 Transition in the industry | The direct market starts to take off

01:45:18 Direct market success and shift of industry?

01:46:27 Frank Miller

01:48:36 Alan Moore

01:50:06 DC bought the rights to the Charlton Characters, Watchmen

01:51:47 Trade paperbacks with Dark Knight

01:53:52 John Byrne Superman in ‘85-86

01:55:13 Will Eisner

01:56:15 Launch Marketing Department for the first in comics

01:58:49 Legion of Superheroes

02:00:42 Most proud LSH mythos moment?

02:01:21 Decisions with characters

02:05:43 Crisis is a huge challenge

02:08:21 Keith Giffen

02:10:21 Collaboration with Steve Ditko

02:14:49 Time & Warner merged, DC is part of Warner Bros, 1989

02:17:00 Titles start to change again

02:18:29 Image comics, Marvel bankruptcy ~1990s

02:21:10 Karen Berger, Creation of Vertigo ~1993

02:23:20 Becoming President and Publisher

02:25:07 Chris Nolan-Batman film, Zack Snyder films

02:25:51 Animated films with Bruce Timm

02:27:44 DC Comics goes under DC Entertainment ~2009

02:29:45 Coming to strong women…

02:32:07 Dorothy Woolfolk

02:34:39 Milestone Media

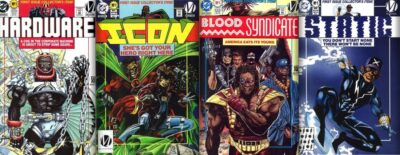

02:36:36 52, Comic book series

02:39:50 Comics done after 2009

02:41:20 DC History Book, Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel

02:43:13 Jules Feiffer

02:44:19 Academic career, post-DC

02:47:36 Visitor, Book by Paul Levitz | Valiant Comics

02:51:06 Ever wrote a story for Marvel?

02:51:52 Talk about that Poker night

02:54:28 Boom, The CBLDF, Clarion Foundation

02:56:47 Awards received

02:58:05 Concluding words

#PaulLevitz #DCComics #ComicHistorian #ComicBookHistorians #CBHInterviews

#CBHPodcast #CBH

Transcript (editing in progress):

Alex: Welcome again to the Comic Book Historians Podcast. Today, we are proud to interview Paul Levitz, writer, editor former Publisher and President of DC Comics, with which he had a professional relationship for more than 40 years. He’s one of the key figures in revitalizing DC Comics through a strong series of managerial and creative decisions, and his writing; in bringing The Visitor to Valiant Comics. Paul, thanks for joining us today.

Levitz: Pleasure to be here guys.

Jim: So, I’m going to start Paul. What we usually like to do is to get into your very beginnings, your history, where you were born, when your interest in comics, and so forth. My first question is, I know you were born in 1956 in Brooklyn, correct?

Levitz: Yep.

Jim: Can you talk a little bit about your earliest days, your parents, what they did for a living, and that kind of thing?

Levitz: Sure. I was born in Brooklyn, almost exactly when Brooklyn stopped being cool. Right about when the Dodgers got out of town, to my father’s annoyance. Dad was the chief clerk for an industrial hardware place. Basically, the nuts and bolts you use to build all the buildings in the New York area, all the towers and the rest, came from their store.

Mom had been a bookkeeper for the year she was working. She’d also gone back to school. Interestingly, for this audience, had been a student of Wertham’s for about two minutes somewhere along the Brooklyn College.

Alex: Wow.

Jim: That’s interesting. Did she have an impression of him?

Levitz: No. No, she just recognized the name, years later.

Jim: Sure.

Alex: Huh.

Jim: Were you an early reader? A lot of the people we talked to, that’s one of the things they remember. It’s they were reading before most of the other kids.

Levitz: Oh, yeah. If I had a super power in my youth, it was my reading. Just voraciously devouring anything that could be read in any direction. Encouraged very heavily by my folks, most intensively my mother.

For the comics, those were the eras when the slightly older kids on the block would have a carton of their comics in their garage, and you’d go sit there, and paw through and find something that you wanted to read. Of course, any kind of book, a great fan of Dr Doolittle when I was very young, and on up then through mysteries and science fiction, and almost anything I can get my hands on.

Jim: You were reading DC comics more than Marvel at the very beginning, is that right?

Levitz: Well, Marvel didn’t have as good distribution in those early years, at least in Brooklyn. I think, nationally, it was kind of a little bit like the situation of some of the independents, and second tier companies have today with the comic shops where going to any comic shop, you can find DC and Marvel, but you can’t necessarily find Valiant or Boom, or Dynamite in every shop.

Jim: Sure.

Levitz: Well, the good shops, the bigger shops, certainly. And obviously, it depends on what the individual customer base really loves in that area, that really determines it. But newsstand distribution was by its nature, kind of random. And if you remember your history in the early ‘60s, DC’s sister company, Independent News, was controlling Marvel’s newsstand distribution.

Did that have something to do with the fact that they didn’t have the greatest distribution, possibly. No first-hand knowledge or evidence. Just seems plausible.

Alex: Right.

Levitz: At any rate, mom loved my reading, she wasn’t too fond of my reading comics. She figured, it wasn’t very good for my eyes, with the crappy print they had in those days. I was restricted to buying, if I remember correctly, three new comics a week.

I’d fallen in love with Mort Weisinger’s line of Superman titles, early on. There were usually enough of those to keep you going, or that and some other interesting DC that would catch your eye because of something on the cover.

Jim: Yeah, we just interviewed his son, two weeks ago.

Levitz: Hendrie?

Alex: Yeah… Did you feel he was a good editor on Superman?

Levitz: He was an extraordinary editor. I mean Mort’s a complex piece of comics history because he was a extremely difficult man with the freelancers that he worked with. But his consistency of editorial work and the imagination that went in the Superman titles in the years when Superman was the only one of the comic characters really with mass media exposure because of the old George Reeves, Noel Neill, Jack Larson TV show, kept the superhero going.

Alex: Right.

Jim: Related to this, you were also a huge Legion of Superheroes fan, right? From the very beginning.

Levitz: Well it started off in the Superman books, I fell in love with that very early on. That was the first material I’ve collected actively. There was a used book store in Brooklyn that would ultimately be a place where many of the people whose names you would recognize for comics, were shopping.

When I was a kid, at the very beginning, they were selling comics for half cover price, because they were used and presumed worthless.

[00:05:03]

As the years went on, they very swiftly caught on to the idea of comics being collectible, and the prices of the older stuff went up, but the more recent stuff remained very cheap, and enabled me fill in an enormous collection fairly early on.

Jim: Now, at some point you started to read the Marvel comics, you were like a Avengers’ fan?

Levitz: When I was graduating public school, my dad was the principle of PTA at that point. Because he was involved in a number of, I guess, the ceremonies or activities, or whatever was going on, he took that week off for vacation, and he was hanging around with me more. He really didn’t care about a three comic book a week limit in the deal, so I was able to pick up a few of the Marvels.

I had read Marvels over the years before. I’d one good friend on my block who love Fantastic Four and argued with me that Fantastic Four was so much better than Legion. In retrospect, technically speaking, he probably was right. But it wasn’t my flavor at that moment, and I had encountered an issue or two of Ditko’s Spiderman in one of the friend’s cartons. But I wasn’t really paying attention to the credits at that point. I thought of Ditko only as the guy who drew the ugly faces.

Alex: Right. Right. Right.

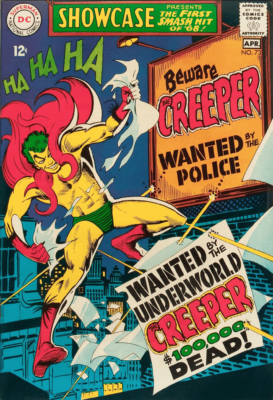

Jim: When Ditko moved over to DC the first time, and was doing Creeper and stuff, you would have been old enough at that point to be paying attention? Were you aware of him when he made the switch?

Levitz: Yeah, well you’re jumping a distance ahead in time, I guess.

Jim: Yes.

Levitz: I mean, not a lot but…

Alex: We’re going to go back he’s just asking a side thing.

Jim: Yeah. Yeah, just in terms of… Ditko went over to DC… What? ’67 or so? In terms of the Creeper?… ’68?

Levitz: Yeah… No… I certainly knew the names by that point. I encountered fanzines for the first time, about a minute before that. We used to go away to the Catskill for the summer. A friend in the country ordered an issue of On the Drawing Board, the then current version of The Comic Reader. And wow, you have all this information about what’s coming, what’s happening, and by that point, I was developing a more knowledgeable taste. I don’t know that it was more sophisticated yet.

Not sure if I can claim my taste in comics today is more sophisticated. But I was much more aware of, beginning to be aware of the names of people. I was starting to write letters to see if I could get my letters published. Starting to do Alco and Proto fanzines.

Alex: Yeah. Right.

Jim: You’re doing that by 11, right?

Levitz: Sounds about right. I think, the first ones done on carbon paper were probably at about 11.

Jim: And that was kind of inspired by The Comic Reader.

Levitz: Absolutely.

Jim: At 14, right around 1971, you actually started up, Etcetera, correct?

Levitz: The main news magazine of the era was Don and Maggie Thompson’s Newfangles. They were a young married couple. They’ve been doing fanzines for a bunch of years. They, I think had the second kid right about then, and life was getting busy and life was getting complicated, and they figured they couldn’t keep this up for very long.

They announced that they were going to out of business within the year. That way, they didn’t have to return any money to anybody for subscriptions, but you could send in an order for the remaining issues.

My buddy Paul Kupperberg and I were sitting around my living room, “Oh my god, we’re not going to know what’s going on.” We scraped together 16 bucks between the two of us, which is a little more money than it is now, but still wasn’t a hell lot of money, and started Etcetera, a news magazine.

We sent copies to Don and Maggie, and a couple of places that would run reviews, and started to get a few subscribers. Not very many in the first few months, but it crawled upwards…

Alex: Was Paul your neighbor? Or how was that?

Levitz: We were middle school buddies.

Alex: Middle school buddies.

Levitz: Yeah. New York terms, he lived, I guess probably a half mile away as the crow flies, but that doesn’t count as a neighbor in Brooklyn.

Alex: Right. Right.

Jim: We’re going to ask a lot about that… Pretty quickly the way it came in to being with Comic Reader. But I wanted to ask first… We use the word fan today in a very different context than what you would describe it back then, a fan was… Can you talk about what a fan meant, back in ’71?

Levitz: Well, I think the difference, it’s not simply a matter of comics today. The word fandom has become an English language general word, and sometimes you even kind of horribly see it used as a verb. “I’m going to fandom that.” Which makes me twitch.

But the definition in the ‘70s, and certainly in the 60’s before that…

[00:10:05]

There were three species of people interested in comics. Readers, which was a near universal thing for young kids. Collectors, people who would actually hold on to the comics after they have read them, and sort of consciously look for specific issues. Maybe buy back issues. Not a lot of people buying back issues, but a few.

And fans, which at that time, really implied that you had some activity. You went to a comic convention, there were very few. You bought fanzines. You made your own fanzine. You might participate in an amateur press alliance, the APAs. You worked at a convention, lots of people volunteered proportionate to the size of the convention compared to today. Because they really weren’t commercial enterprises yet. You did something. You made indexes.

I just found a lose leaf notebook, I hadn’t seen for a decade or more. In which, I had laboriously indexed 50 or 60 or 70 different titles over a number of years.

Alex: Wow.

Levitz: Titles, issue numbers, who credits, if they were available. And I must have done between when I was 10 or 11, and 14 or 15, maybe 16.

Alex: Wow. That speaks a lot to your personality of being very organized.

Levitz: Yeah, or obsessive compulsive. One or the other. [chuckles]

Alex: One or the other, yeah.

Levitz: Both, maybe.

Jim: I just have one other question. As you were doing these early ones… Well, two actually. One, were you involved at all in Legion fandom? And then that I know is a real thing at the time.

Levitz: I don’t think there as a distinct Legion fandom at that time. I think there were people who felt it was a favorite book but there wasn’t the same level of segregation between the different sub-fandoms, I think, that you see later on.

Well, it started as the distinction between the DC and Marvel fandom, certainly. Stan was doing such amazing P.T. Barnum-like rousing of the Merry Marvel Marching Society. The rank-order that you could earn as a Marvel fan by getting a letter published, or finding a mistake, or buying three or more titles, or whatever the numbers were.

There’s certainly were people who were distinctively fans of other things, but the first Legion focused APA, Interlac… I’m going to say, probably ’75, could be ’74, something like that.

Alex: Right. Did Dave Cockrum’s run have anything to do with that, you think?

Levitz: It didn’t hurt. I think a lot of it came from the work that was done on the fanzine Legion Outpost.

Jim: That was what I was thinking of, of things like that. My other question, then I’ll turn you over to Alex was, when you were doing Etcetera… This was around the time that Kirby had left Marvel, and had gone to DC and was doing New Gods.

For me, and I was born in ’59, that was when I really started to pay attention to artists as artist. I followed Kirby over to DC, otherwise, I was reading DC anyway. When he was doing New Gods, how where you interacting with that? What were you thinking about? Because later on, Dark Side obviously becomes very important, in terms of, when you’re doing Legion.

Did you think it was something special? Or did you think it was clunky in the writing? How were you processing it as a teenager?

Levitz: In terms of how I was interacting with it, we started Etcetera right as Jack’s work was coming out from DC. We didn’t get to break the story but we were certainly covering it almost from the beginning.

I vividly remember standing by Carol Fein’s desk, she was Carmine’s secretary at that point. She would get the packages from Jack. She’s be opening it up and, “Here, Paul, you want to look? Here’s the new…”

Jim: Oh, wow!

Levitz: It was so different from what had been done before. The flaws that we look back on now, are real. But we have a tendency, I think, to lose track of how outrageously courageous it was and how much it set the model for so much of what comics have done in the ensuing five decades. The idea of the inter-linked worlds, the idea of inter-linked titles, the idea of consciously building that kind of mythology.

Up until then, each of the comic book mythos accreted over time but weren’t planned. Stan wasn’t keeping notes so he would misname the Hulk an issue or two in. He’d forget what somebody’s power was, and it would work differently.

The DC editors would no more focused on it. Bob Kanigher who was doing Wonder Woman would contradict himself completely two issues later with a story that went in a whole opposite direction.

[00:15:03]

Julie Schwartz’ books that he was doing with Gardener Fox and John Brumm as the writers, were more structured but they weren’t really focused on mythology. Even when you start things like Flash of Two Worlds, and you begin to deal the idea of a multi-verse, it’s so thrown-out story, and it isn’t returned to for a year and a half.

Jim: Sure… And this was just book after book coming out, and it all building upon each other. It really revolutionary, wasn’t it.

Levitz: And from one guy’s imagination. Weisinger’s Superman books, had as much mythology but it had been accreted over a significant amount of time, and by a team of writers…

Alex: Many people.

Levitz: Somewhat directed by Mort in that, and certainly encouraged by Mort, and he set a tonality to it. But still, not with the same scale to it.

Jim: Were the people in the DC offices divided about it or did they all recognize, or it just mystified by it, not understanding it? What was happening with it? Or did they appreciate what he was doing.

Levitz: I don’t remember any conversations with any of the older folks in the office about it. The assistant editors who were… I don’t know, between, I guess, six and ten years older than I was, treated me as a peer because they’d come out of comics fandom.

They were very encouraging to me, very supportive of me. This is the editor at Marvel in that period as well. The major editors at DC, were my parent’s generation, and they were terrific with me about doing the fanzine. They were very supportive. They gave me lots of information, lots of help but they certainly weren’t about to bad mouth a writer or an artist, or compliment one, for that matter.

Alex: Right. Right. Just to give a quick background to the listeners, On the Drawing Board was a fanzine started by Jerry Bails which was then changed to The Comic Reader. Then it became defunct despite winning an Alley Award in 1969.

Paul, shortly after you started Etcetera, you bought The Comic Reader when it had stopped publication, and you were 15 at the time? I guess, I have some questions about that, what exactly did you buy? Was it the name? Was it the subscriber list? How much did it cost? Tell us about that.

Levitz: I didn’t buy it.

Alex: Okay.

Levitz: Mark Hanerfeld at that time, who was the last editor of The Comic Reader was working as Joe Orlando’s assistant, doing other sorts of freelance at DC, occasionally. I’m up at the DC offices, Mark comes over to me one day with a giant manila envelope full of coins and index cards.

Alex: I see.

Levitz: “Here. You’re doing what I set out to do.” Because we were managing to publish every month, and run the listings. “Why don’t you take this. Fulfil these subscriptions.” So suddenly, we were The Comic Reader, and suddenly, we were one of the two largest circulation fanzines of the time, and really the largest in circulation, one that had content. Allen Light’s original version of The Buyer’s Guide was all advertising. Hence, started to run things like Don and Maggie’s content, yet at that point.

Alex: For the next year you published it as a combined name, Etcetera and The Comic Reader, and then they ran like that until issue 90. It went like that for a while, so what exactly happened? Did they split back up into two separate things? What happened with that?

Levitz: Yeah. Well, I transitioned the core fanzine to The Comic Reader because it was a better name. And I guess, about two years in to doing the fanzines, I guess, I got still more ambitious. By then, I had talked my parents into letting me replace the tenant in the basement, so that I could have a studio set up there to run the business out of.

Kupperberg had gotten back involved. He wanted to do an article fanzine, so we put the name Etcetera on that. We also started working on the New York Comic Convention program books around that time.

Alex: Were you both working on both of them or were you working on TCR and he was working on Etcetera?

Levitz: I was the editor of TCR and he was the editor on Etcetera. I was running the business… Huh, if you want to call it a business, of both. He was occasionally contributing articles. It wasn’t just the two of us, there were other folks who were hanging around. A lot of the young people who were moving to New York from fandom to break in to comics at that point, would hang out in the basement and be helpful, be part of it.

People would either be regular columnists. Doug Moench who would write about a thousand Marvel comics, I think…

Alex: Right. Right, a lot.

Levitz: Warren had a column, at one point.

[00:20:00]

Mark Evanier, had a column, occasionally. Tony Avelarhad a column. Names you would recognize.

Alex: You increased the circulation with the fanzines. You got a two best fanzine awards. How did you attract artists like Jack Kirby, Chaykin, Simonson and Buckler to work on the covers? Were you hanging around at the offices? How did that connection come about while you were working on the fanzines?

Levitz: It’s a very different world. I mean, at that point, there’s only about 200 people working in American comics, with the creative jobs, and all but a handful of them are in the New York area. You would see the guys either at the offices, most often, at New York ComiCon, the one time a year happen.

I think the second Sunday monthly trading conventions hadn’t started. Some of the guys I would see at that bookstore I mentioned. My friend’s bookstore, Chaykin and Simonson were regulars there…

Alex: Oh, cool.

Levitz: In the years they were living in Brooklyn, when they were starting out. For the most part, it was their way of saying thank you for a free subscription. Some of them, I remember paying 15 or 20 bucks for a cover. I still can’t remember whether Kirby took any money or whether he did the cover for my 100th issue just as a thank you. He’s a really nice man.

Alex: I saw that Tom Fagan wrote an issue in the 1973 Etcetera about the Rutland Parade. Did you ever meet Tom Fagan?

Levitz: I met him later on in the years. I never made it to Rutland, sadly.

Alex: Okay. Okay. Now, you did the program book for Phil Seuling for 1973 Comic Art Convention? How did that come about? Was that because of your fanzine work? And what kind of guy was Phil Seuling?

Levitz: I think we did ’74 to ’76.

Alex: Hmm, okay.

Levitz: I had met Phil many years before when I was a kid. He had briefly run a used bookstore in Brooklyn, that also carried some comics. That was a couple of doors down from a cousin’s real estate office. My dad was doing a side job there. I think he’d actually rented the space to Phil. Which may not have been a favor for Phil because clearly it wasn’t a very successful business.

But then when we were starting with The Comic Reader, Phil offered us a free table at New York Con at ’71, if we would sell other people’s fanzines as well.

Alex: Why?

Levitz: Because they couldn’t have space. And from then on, both at New York Con and at what were called the Second Sundays the Dealer Table Only, monthly cons he would run a couple of years later, we had a fanzine table. That’s how I got to know a lot of the young people, who were active in fandom across the country. Selling Gary Groth’s Fantastic Fanzine, things like that.

I was involved with Phil and the conventions from that. I guess when Sal Quartuccio, who had done a beautiful job on the fanzine Faze, gave up doing Phil’s program books, he needed somebody, and he asked me and Paul to step in.

Alex: All right. So then, my understanding is that you sold The Comic Reader in 1973 to Street Enterprises?

Levitz: Yep.

Alex: Because you were now working more for DC at this point. Tell us about that transition? At this time, you’re about 17-ish.

Levitz: 16.

Alex: 16, okay.

Levitz: Yeah. Jerry Sinkovec and Mike Tiefenbacher had been doing a beautiful job with The Menomonee Falls Gazette which was a fanzine basically running syndicated newspaper strips. They had managed to talk to various syndicates into allowing them to run them. I’m sure the syndicates were charging something. They figured out how to run that as a business. They were running it smoothly.

I was ready to give up the fanzine because I was starting college, and working at DC a couple of days a week to pay for college. They were ready to take it on, so we worked out a deal. Not a massive financial transaction either, but good. It was nice to see the heritage continue.

Alex: Yeah. Right. Also, then this is a little bit of a backtrack, but you’d been hanging around the DC offices as part of the fanzine work since early on, and you started doing some freelance work at DC for Joe Orlando. This was earlier, since 14 years old or so, 15?

Levitz: 16.

Alex: Oh, so this is all 16. Okay. So, what were you doing? You were writing letters, columns? What was going on here?

Levitz: I’m a high school senior. I’m walking through the offices doing the fanzine stuff. One day in December, Joe calls me in and he says, “You want to write my letter columns, kid?”

I said, “I’m not a writer.” He said, “You write your fanzine. You write well enough to write a letter column.” This is not exactly a high bar, I admit. But, so suddenly, I was a professional writer. Getting paid to do this.

Fairly shortly after that, I was given the opportunity to do the DC equivalent to the bullpen pages, direct currents, mix the world of DC, and had branched out that way.

[00:25:05]

Then, the summer of ’73, Joe’s assistant, Michael Fleisher, was going to take the summer off, as an extended vacation. He was a writer, and he had a major writing project or something he wants to work on, and Joe asked me if I would fill in, “Sure!”

The day after I graduated high school, aged 16, I’m an assistant editor on the masthead. Working a couple of days a week. Michael never comes back. I didn’t kill him. He went off to write and do some really interesting stuff. He went to Africa eventually.

Alex: Okay. So, there wasn’t a homicide involved, that’s good.

Levitz: As far as I can recall, I’ve not killed anybody.

Alex: [chuckles]… And then your first staff job was assistant editor under Orlando, right?

Levitz: Yup.

Alex: So, tell us about that.

Levitz: Joe was doing a lot of mystery books, one or two things that verged on the superheroes. A couple of war books, I think, at the time. And from time to time, depending on what genre DC was getting into that week, Carmine would walk in and tell him he’d just put two sword and sorcery books on the schedule, “Come up with them.”

As an assistant editor, pretty glum on the mystery books, you did a lot of rewrite. Joe bought a lot of stuff, either for very young writers or very old writers. And it’s kind of a tie which one of them needed more help.

I felt I had learned enough to write. I began to do a couple of short mystery stories for Joe and Tex Blaisdell who was editing a couple of titles at that time. As opportunities opened up, I grabbed them. So I got to do, when Carmine wanted to launch sword and sorcery titles, I got to come up with Stalker, and get Steve Ditko and Wally Wood drawing an original series I created at age 17. Insane, right?

Alex: Pretty awesome.

Levitz: And wrote some Phantom Stranger. Wrote an issue of Karate Kid. Wrote a few Aquamans.

Alex: When Gerry Conway, he came over from Marvel around this time as well, is that correct?

Levitz: Yep. Gerry wanted to try his hand at being an editor. He, I think, had been pissed off at the dynamic with Len and Marv who were sharing the editor-in-chief role there for a while. I forget the exact details but function of who got which Spiderman book to do or something.

He came over as the very young editor, and had to really create a new line of title, he wasn’t given any thing much of the established published materials to work with. I took on being his assistant as well. Got an extra day here and there out of it. Learned a lot. Gerry is a really solid writer.

Alex: Was he an influence on you as far as writing style and such.

Levitz: Oh, absolutely. Gerry, Denny O’Neil who would edit my stuff about a minute later. Anybody, who’s hand touched my work in those early years was an influence because I was so busy learning. I was so awkward and so young.

Alex: Right. Yeah, because I saw that on some of the writing credits at the time. It’ll say, “By Gerry Conway and Paul Levitz” like it’ll be a combined writing credit.

Levitz: Usually, that’s the case, where Gerry’s schedule was so full, that he would have the idea for a story but wouldn’t have time to do the breakdowns of it for the artist. And I’d jump in and do something like that or vice-versa.

On Aquaman, there were one or two issue where… Because Carmine was not impressed with my early writing. He wanted somebody more experienced to work on it. So, I might have plotted and Gerry might have executed it. But it very rarely was anything resembling a marriage of equals. He was vastly more experienced than I was.

Alex: I see… More experienced. You were doing this, while you were starting college. So, you were kind of doing two things at once here, that sound both very busy.

Levitz: Yeah. I think it’s pretty clear over the years that I have a pretty good capacity for work.

Alex: Yeah. You can do a lot of things at once. What was the DC environment like in those days as far as- This is like towards the end of Carmine’s run there, were you treated well as the new person? This was also around the time with the Seigel and Shuster law suit; Neal Adams was DC Comics’ big gun in those days. Tell us about that over all environment at the time.

Levitz: I guess the hardest thing for the current generation of fans to focus on, is how small the environments were. You’re used to thinking of DC and Marvel as being part of these giant corporations, and having so much influence across the world. DC was owned by a corporation, Warner Communications, but it really was almost a free-standing group of about 30 people, and had very little interaction with the rest of the corporation. Marvel was even smaller, and part of an even smaller organization. These were really small communities.

[00:30:03]

In general, the older guys at DC were incredibly supportive. I was a very young kid, and occasionally, I was a smart ass. I was occasionally trying to do things where my reach exceeded my grasp by suspect. So, there were, from time to time, problems based on that. But I think they were probably kinder to me than I would have been to me or to them.

Mostly, I just learned an enormous amount from them because, Chaykin’s line is, “We were there for the end of the beginning.” And we really got to know the people who created the business that way, and hear the stories of the beginning.

Alex: Right. What was your impression of the Siegel and Shuster law suit at the time, like while it was going on in ’75?

Levitz: That was no law suit. That was a public relation campaign.

Alex: Public relations campaign, there you go.

Levitz: Jerry had lost the last opportunity to take the existing case he had had to a higher court. A couple of years before, he and Joe were both in a pretty miserable financial shape. And with the Superman movie in pre-production, or production, at the time, he felt that he had an opportunity to embarrass Warner into being more generous to them. And that worked.

I got to know Jerry and Joe at that point, to my pleasure remained friends with them for the rest of their lives. I think, all of the, certainly the young people in comics in the mid ‘70s were very conscious that the deals that had been in place for creators had not worked to the creators’ advantage.

Depending on where you stood philosophically, or politically, people would either argue that they have been ripped off, or people would simply say, “Hey, it was a time when this was the norm, but the norm sucked.” The people who created all of this wonderful stuff should have done better, as a result.

There was certainly a lot of consciousness of it, a lot of discussion of it, a lot of frustration about it, and a hope that in the ensuing years we could make the industry a better place somehow.

Alex: Right. Which I think we feel like you did it. Did you have dealings with Neal Adams? He was running Continuity with Dick Giordano. What was the relationship with DC Comics and Continuity around this time?

Levitz: If you’re talking about Carmine’s last days, there really wasn’t a hell of a lot. Dick would ink something occasionally but Neal was doing nothing or almost nothing in comics in Carmine’s last couple of years. After Jenette arrived, Neal became much more involved with DC for a while, and did a bunch of covers and certainly gave a lot of background and advice to Jenette about his view of the industry. He’s never been shy about his views.

Alex: Right. What was your relationship with Carmine Infantino, as he was ending…? Did you have much of a relationship with him at the time before he left as publisher?

Levitz: It was a small place; he had a relationship with everybody. He was the boss of the place. As I’ve said, there were 30 of us, he knew everything that was going on.

Alex: This is a tough question. Do you feel like he was a good publisher?

Levitz: I think Carmine was an extraordinary artist. He was a great cover editor. He was a very good editorial director. When you look back and you look at the group of people, he brought in to roles as editors: Joe Orlando, Dick Giordano, Joe Kubert. Those are three people who contributed a tremendous amount to the company in the next batch of years. You look in talent he brought into DC in those years: Kirby, Ditko, those are great contributions.

It was a crappy time to be on the business side of the company. The comic book business as it was configured, was shrinking out of existence. Lot of pressure. Carmine was not trained in business, educated in business, really incredibly comfortable on the business side of it, on my opinion.

He did somethings to try to make it better for the talent. He started the return of original art at DC. He started pre-print payments at DC. But he wasn’t able to put all of it in place firmly because of the difficulties of the economy. He wasn’t able to stay a steady course because every time the company took two steps in a given direction, business sucked, there was corporate pressure, and he would go shooting off in some other direction to try and respond to it.

I don’t think he did a great job, in his years in the business side, but I’m not sure if anybody could have, at that time. Marvel was not triumphing as a business company in those same years.

[00:35:01]

Alex: Interesting. All right. So, Jim, you’re going to talk about freelancing.

Jim: Yeah. For me, what’s just astounding, is for you to create a character like Stalker, and to have Steve Ditko and Wally Wood on inks working on it. Was that thrilling or more intimidating?

Levitz: I don’t intimidate a lot, I don’t think. And I certainly was too young and too dopey to intimidate much at that age. It was thrilling. Carmine had literally had stuck his head in and said, “Joe, I need two more sword and sorcery books. One’s coming out in January, you’re two months late on it, and one’s out in February, you’re only one month late on it.” I may be getting the months wrong but I think that’s about what it was.

He walks out and I say, “I could write one, you know. I like sword and sorcery, I can try that, Joe.” And Joe said, “All right, come in with something tomorrow.” I went home and I channeled my best Michael Moorcock and came up with Stalker. He handed it to Ditko, who needed work. And I’m just… amazed. [chuckles]

Jim: Were they of the hopes that you all were going to come up with something sword and sorcery-wise, that would compete or have the same popularity as Conan. That seems to be what everybody wanted, was to have the next Conan.

Levitz: I guess. I mean, Conan was doing well. Remember that comics had a long history of jumping on genres, and trying to figure out what the next hot genre was. And that’s the way the publishers thought. “Sword-and-sorcery is working, start three sword and sorcery books. Who knows maybe one of them will work?”

Jim: In 1975, you also co-created a character that you were probably shocked later to see it become well known as it was. That was Lucien the Librarian, who premiered in Weird Mystery Tales 18, in sort of a PLoP style introduction and he was going to be the host of Tales of Ghost Castle, and was for three issues.

Levitz: No, he started for Ghost Castle. They launched Ghost Castle as a new book, Tex Blaisdell was going to be the editor. I was going to write most of it. And it needed a host, and the style of Joe’s books was to be pseudo-biblical so I played with a name that… I didn’t think we could do Lucifer, but I played off Lucifer for Lucien. I still have Joe’s original sketch hanging on my wall.

It was not a very deep conception, really, it’s what Neal did with him years later, in Sandman that made him an interesting character.

Jim: Do you remember writing that little short intro though, in Weird Mystery Tales? Because I just read it this morning, and it is there.

Levitz: Really?

Jim: It’s a three-page story interacting with the witch that was the host from Weird Mystery Tales.

Levitz: Really?

Jim: Yeah. But with your writing credit. Yeah, and it looks like something right out of PLoP. And he’s explaining, that he’s doing research, because he’s going to be the new host in this new book, Tales of Ghost Castle.

Levitz: I’m looking it up. Hang on.

Jim: Okay.

Alex: [chuckles]… Because this is the cataloger we are talking to, so he will verify.

Levitz: No, I would just remind myself… A couple of years ago, there was one of those Fan/Pro trivia contests, things at San Diego. Mark Wade was answering all the questions about my writing before I could…

Jim: From Weird Mystery Tales. It’s the last story in the book.

Levitz: It’s basically a house ed.

Jim: Yeah.

Levitz: I guess we had a page to fill and they said, “Fill it.” … “Okay.” I have no memory of writing this.

[laugher]

Levitz: My print is on it, you’re right about the credit, you’re wrong about the page count.

Jim: Yes. All right… Speaking of which, we’re talking about the mystery books, I wanted to ask you something that’s of personal interest to Alex and I, which is, there was a number of Filipinos, obviously, that came in and were hired by Infantino for DC at the time. Many of them were working on mystery and war books.

A lot of people think of it as basically five or six individuals, but there was a huge number of artists that were working on those books at that time. You, as assistant editor who are working with those, you were working with a lot of those, correct?

Levitz: Part of my job, again, it’s a different era, you had to send the materials back and forth in a courier package, there was no Federal Express. You sent it by a company that literally have someone take it, carry it on a plane and bring it over. It was very expensive, so you would only send a package, I think, once a month and they would send the art back once a month, and once every two weeks. Part of my responsibility was putting that all together.

If you had to make a call over there to check on something, I think we had to get Carmine’s permission, to call that long distance. I remember once, being on the phone and Alex Niño was late on something, and the answer was, “Yes, we are sending a runner out to find Alex.”

[00:40:08]

[laughter]

Levitz: Okay.

Alex: It’s like Indiana Jones.

Levitz: It was a fascinating outsourcing. Tony DeZuniga and his wife Mary had set up the first version of it and then Nestor Redondo took it over. Tony was a Filipino who had moved here, a wonderfully talented artist. He was aware of the depth of comics culture over their number of great artists. And the artists over there, at the time, were making, if they were really terrific, four or five dollars a page penciling. And the top American rate at the time was probably about 60, $65 penciling.

A deal was struck to pay them like three times what their usual rate was, maybe even a little more than that, but a third of what the American rate was. Both sides thought they were screwing the other amazingly and everybody was having a fabulous time.

[laughter]

Ultimately, the Filipino artists who participated in that, many of them got very well off, by Philippine standards. A lot of them moved to the US. A lot of them went to work in California in animation after that. Just incredibly talented people.

Alfredo Alcala who might be the fastest artist who’s ever worked in comics. Alex Niño with his surrealistic style, Nestor Redondo, beautiful stuff. Less famous but wonderful guys like Gerry Talaoc, Ruben Yandoc… You’re right. It was quite a crew.

Jim: Because you were able to get them at a… or DC was able to get them at a cheaper rate, and without other demands, was that a negative in terms of older artists’ negotiations in terms of both pay but also things like getting their art back?

Levitz: I don’t think so. They weren’t, the established artists in the field were generally getting all the work they could handle. It probably kept some of the younger artists from breaking in as quickly, because they had to do stuff that looked that good to compete. But I don’t think it was putting any pressure on the older guys.

I mean business sucked. There was not a lot of money to be had by anyone, for anything in any circumstance. This didn’t make it any worse.

Jim: The first title that I can see where you have a reasonably long run on was Aquaman, is that correct?

Levitz: Yeah… I think I managed about five or six on Phantom Stranger before it got cancelled. But Aquaman is certainly the first superhero title that I…

Jim: Okay. The first issue that you did was by Grell, but all the rest were Jim Aparo, would that be right?

Levitz: Yeah. The one with Grell was just a backup, when it became the lead feature a few months later. Aparo had been doing the Spectre and he moved over to take over Aquaman, which replaced it.

Jim: Had he done the Phantom Stranger issues that you had done or was that somebody else?

Levitz: No. Mine were, I think, all by Fred Carillo, one of the Filipinos.

Jim: Okay. Were you happy with Aparo on Aquaman? Did you care about Aquaman? Was he a character you had any connection with?

Levitz: I had read of Aquaman through the years. I can’t say I had any particular passion for him, going in other than, it was an opportunity to do a superhero thing, and Joe wasn’t usually on the superhero business.

Aparo was, if not the best artist at DC for superhero material that time, certainly arguably the best. So, I was thrilled.

Jim: Yeah, that’s great. Again, right of the bat you were getting some of the best people working with you. That’s exciting. Was that educational, was that helpful, being a rookie writer to be working with people that had experience or were just innately really solid. Did that help you learn to be a better writer?

Levitz: That’s an interesting question. I never thought about that. It probably did. One of the things that is distinctive about my work, I guess, I’d say… I’ve been told by many artists over the years, that I write very drawable scripts.

Art direction is a hidden art form in our business. Some writers who write very good stories, write very difficult stories for artists to draw properly, and very frustrating for the artists. Maybe it’s because I was taught at Joe’s hand, who obviously had an enormous role in shaping me as a writer. But it’s also certainly possible that seeing what Aparo or Ditko, Grell, the other really talented people I got to work with in the first batch of years, did with my work, that certainly could have helped in all of that.

[00:45:02]

Alex: I’ve heard that about yours and Archie Goodwin’s. That that’s something you two had in common. That you can write scripts that artists felt that it was like cued for the artist to draw. That’s an interesting characteristic.

Levitz: I’m honored to be in Archie’s company in a sentence. He was way over my pay-grade. Remember also that Archie was a cartoonist himself. He was able to think visually in a way that very few of us can.

Jim: Can you draw at all?

Levitz: Nope.

[chuckles]

Jim: No interest? You weren’t an artist as a kid at all?

Levitz: No skill. I took a couple of art classes. I don’t think they threw me out but they should’ve.

Jim: Ha. I want to kind of be a bit of a fan myself now, and talk about All-Star Comics. When you took that over in 1976, was that something that was a dream project for you? Were you interested in those characters a lot because there seem to be a great love of those characters in that All-Star run?

Levitz: Thank you. Well the first comic I can remember buying myself, off a newsstand, was a part of the first JLA-JSA team-up, so I’ve loved those guys for a very long time.

When Jerry came to DC, as I said, he didn’t get assigned to a lot of existing books to work on, as an editor. He had to create stuff or revive stuff out of DC’s history. A couple of the things he revived, he didn’t know much about the background of, but he knew had been successful for years past: All Star Comics, Blackhawk.

In the case of Blackhawk, I was never a Blackhawk fan. I didn’t know the material particularly well, and so Jack Harris, who was Murry Boltinoff’s assistant editor, as his full-time gig, stepped in to be Jerry’s other assistant on that and really provide the background information.

On All Star, I’m sure Roy Thomas was feeding Jerry a tremendous amount of information because they were good friends. But since I knew those characters well, that was a natural one for me to help out on.

Jim: In terms of bringing in Wally Wood on board, where was Wally Wood at the time? How was he doing? Was he in a good place or a bad place? Was he getting a lot of work? Because I’ve heard different things about his participation on this.

Levitz: Well… You didn’t hear anything about him being in a good place that time? He’s in the last years of his life.

Jim: Yeah. Trying to be a little diplomatic but…

Levitz: Joe Orlando had been Woody’s sidekick back in these days. Rented a studio space with him, had a long-standing relationship with him. In the mid ‘70s, I don’t know what Woody had been doing immediately… Previously, probably he was the strips for the army newspapers. He’d package two or three of them, Sally Forth. I forget the names of the other one or two.

Alex: Shattuck and Ken.

Levitz: Okay. I don’t know if those had wrapped up or were just not paying as well. So, he was trying to get Woody more work at DC. I don’t know whether it was a function that Carmine liked Woody as an inker but not as a penciller, or that penciling was too time consuming for Woody, but Joe came up with this approach of taking a couple of artists who were good layouts, and good storytelling people but weren’t people Carmine would necessarily sign off on to do a book, and have them just layout pages at a lesser rate than penciling, and Woody would get a higher rate for doing “finishes”, rather than inking.

Jim: This was Ric Estrada on the All Star book, right?

Levitz: Ric Estrada on the All Star, and Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez on Hercules.

Jim: Oh, that’s right.

Levitz: Jose was as good an artist has ever worked in comics, but he was just at the beginning of his career. He had not done superhero work. He was new to American comics. He was still learning the dynamics that he would master in such an incredible way. Those are beautiful issues, those Hercules issues.

Jim: I love those, yeah.

Levitz: I think in Woody’s case, these “finishing” didn’t take him any more time that inking. Because he could add the additional drawing at the same speed, he would ordinarily ink a page. He was just so good. He was not in the best of health already at that time. He was not in the best of emotional health, I suspect either, at that point. He was kind of worn and beaten by life. But worn out Wally Wood’s still better than 99% anybody ever did comics.

Alex: Right. Right. They’re still beautiful issues.

Jim: That castle stuff in the past, that stood out in my head so much at the time because I don’t know if I’d seen a lot of Wood, I’d seen those Daredevil issues.

[00:50:00]

But I saw that and it just stuck in my head, how much I was enjoying that series, based on that.

Levitz: The story behind this story is, Woody was about to start penciling the book, Carmine had left, I was writing the book. We had a lot of freedom on what to do, and it was, “Woody, what would you like to draw?” And he did a little pencil sketch of Superman, and a suit of armor on a napkin. I don’t remember… We were probably in the Warner cafeteria… That was the basis of that story.

Jim: Oh, that’s great. I wonder if that came from the… There’s an episode of the Superman series, where he’s flying through the air in a suit of armor.

Levitz: I don’t know. I think Woody loved knights in armor. I think All Stars were his last mainstream work. I think he did some of the Wizard King stuff after that. But that was about it for his life. Sadly.

Alex: Yeah, then there’s kind of questionable, later Sally Forth things he did in like 1980 or so.

Levitz: I don’t know if I ever seen those.

Alex: They’re pornography comics.

Levitz: Well, the line between, any of the Sally Forths and pornography, probably is a pair of bikini panties.

Alex: [chuckles] That’s true.

Jim: You continued to write All Star, and did a lot with it. And you were really getting into… It was one of the early examples of playing with the past, and developing a prior methos, that later on became something that a lot of people did. But you were doing it there in a really interesting way, in playing with the whole Earth-2 notion.

Who were some of your favorite… Were there characters that you were especially interested in playing with? Like Wildcat or others?

Levitz: I think it depended on whose life I was screwing around with at the moment. We did a bunch of stories with Doctor Fate, who I always liked as a character. We did a bunch of stories with the original Green Lantern having some challenges in his life. We screwed up Wildcat for a minute or two. Power Girl was always a lot of fun.

Then of course, with Joe Staton and Bob Layton who were working on the book, I created the Huntress character. Then playing with Huntress and Power Girl together was always a lot of fun. That was a very different Superman and Batman riff.

Jim: A team that stuck almost to this day, although obviously, Huntress is a very different character. Was she a creation entirely of yours?

Levitz: Definitely a co-creation with Joe and Bob.

Alex: Bob Layton came from the Woody school, right? So that seemed like a nice transition from Woody’s angst.

Levitz: Yeah. I think he was assisting Woody at the time. So many people did over the years, that it’s hard to keep track of the people who were Wally Wood assistants or Dick Giordano’s assistants.

Alex: Well, that’s true. Yeah, you’re right.

Levitz: Both were keepers.

Jim: I’m going to go off script and just for a minute and ask you something that takes place later, which is, this was all obviously Earth-2. Did you miss that after Crisis? Was it the right thing to do or a mistake to get rid of the alternate Earth?

Levitz: The logic at the time, and it goes back to actually something Gerry Conway had suggested in the ‘70s. The logic was that the multiverse was too complicated for the readers. We were still thinking of our readers as primarily being 12-year-olds, 13-year-olds. By the time of Crisis, we thought they were a little brighter and starting to be a little older, maybe 16 years old. But all this multiverse, the metaphysics of all of it seemed awfully complicated.

Marvel was doing very well. It was one of the advantages of Marvel that they had this singular, seemingly logical continuity. That was the logic behind condensing it. I certainly miss the characters, but they all came back eventually.

Jim: Yeah… Of course, that also didn’t do the Legions any favors. And your first Legion run would have been back in this period of time too. Can you talk about that? Now, this is the second one you did with Keith Giffen, but your first run at the Legion. Being one of your favorite books anyway, what was it like to actually be working on that, and were you satisfied with it?

Levitz: Jim Shooter went over to Marvel, to be an assistant editor there, and he had been doing Legion again. I think I would have killed anyone who stood between me and the book at that point. But at that point I might have become a murderer.

But Denny O’Neil was editing it for a minute or two, and he had no idea who the characters were so he really needed somebody who was a deep Legion fan. He was very happy to let me have the assignment. I went through a number of editors during that run: Denny, Al Milgrom, principally.

I’m not happy. I wasn’t even happy then with the work I did. It was a period where I over committed myself as a writer. So, there were too many fill-ins, too many jobs I plotted but didn’t dialog.

[00:55:02]

At the same time, it’s a hard book to get an artist to settle in on regularly. Jim Sherman who’s an amazingly talented guy did a bunch of them really beautifully. Mike Nasser, later used the name Mike Netzer, did a number of stories very nicely. But there’s no continuity to it. Part of that is my fault, and part of it was the times we were in. So, no, I wasn’t particularly satisfied with that period.

Jim: Ditko even did a few issues, right? Was that under yours?

Levitz: After me.

Jim: That was after you. Okay… Now, we’re coming up on 1976… Oh, one other question, you did an issue of Karate Kid. Was that your choice to do? Was that something you wanted to do? Or you just did it as an assignment.

Levitz: No. I mean, again, Carmine had come down the hall and said, “We’re going in the kung fu business, Joe. Start a kung fu book.” Denny created Richard Dragon which he had originally developed in a novel for his kung fu book. Joe was trying to figure out what, he said, “Hey, we’ve got a kung fu character” … “Can we borrow him from the Legion?”

At that period, editors were very much in control of their individual titles, so it was sort of a bit of maneuvering to make the deal with Murray Boltinoff who’s the editor on the Legion, whose office was next door. But we were able to bring it over.

I wrote the first… Then it was a period where my writing really hit the rocks with Carmine, so the book went over to David Michelinie to take over.

Jim: I see. So, we get to ’76. Now, you’ve been at NYU for three years at this point. In a business undergrad and then master’s program. That’s what, a five-year program?

Levitz: Yeah.

Jim: And after three years, things are going so well at DC that you were making more money than you were going to make if you graduated from that program, is that right?

Levitz: Yup. Jenette had come in and the dynamics of the company was changing. It looked like there was some hope.

Jim: And that’s my segue back to Alex.

Alex: Okay. In 1976, there were changes. Carmine was essentially let go at DC Comics. Sol Harrison became president. Jenette Kahn became a publisher. There’s quickly a change in culture at DC Comics.

Tell me what you mean by “There is hope now.” You became a full-time editor at this point. Tell me what you mean by “There was hope” and what was not looking like it was hope before she came.

Levitz: Well in the ‘70s, the prevailing wisdom was the comic book business was dying.

Alex: Yeah, okay.

Levitz: The business model, what you call the product life cycle, in marketing terms, that the traditional comic book had been in, was clearly coasting to an end.

The affidavit returns really have very little to do with it. There are a lot of fans who sit outside the business who come up with complicated theories about what goes on inside the business. There’re several flaws to that.

First of all, its profound ignorance… I share, as a kid, I wrote a column called Comic Economics a few times for Joe Brancatelli’s fanzine. It’s naïve. I didn’t know much about business. I certainly didn’t know insider information, and the comic book business was not a very public business. No comic book companies were public, so that there were no published information, about on any detail, so that even if you knew of something, it would have been very hard to research.

So, you have fans who’d grab on to theories. In places like San Francisco, you had early comic shops and a lot of early dealers, so there were a lot of purchases of new number ones, off what we call the cash table, from the ID distributors before the book went out to the traditional newsstands.

Some of the guys who experienced that say, “Oh, well, in fact, Green Lantern, Green Arrow was selling fabulously because I know in my distributor, we bought every copy that was there.” Yeah… That’s not what happened in Iowa. Or the newsstand system had many problems, affidavit returns being certainly one of them. But that’s really a detail in the story.

I mean, the essence of the story was that this form of distribution, which had existed in America, for magazines wasn’t a great fit for comic books to start with because it was designed for advertising supported magazines. Maximize circulation, even if it didn’t generate any profit from the circulation per se because the profit would come from advertising. Comics never did a lot to profit from advertising so we weren’t a great fit to start with.

So, in the 1950s, when Playboy could sell over 90% of the copies it put out in the newsstand, a good selling comic book might sell 50 or 60% of the copies it put out.

[01:00:02]

By the 1970s, Playboy is selling 50%, 60% and the comic books are selling 30%. We’re printing three to sell one, which pushes up the price, lowers the profitability. At the same time, the number of newsstands keeps declining, and locations of the newsstands are becoming less and less friendly to children. Based on where the population is, and how retail is functioning in this country.

So, a lot of things are coming together, and there’s no hope in sight for that. By the end of the ‘70s, there are a few comic shops. But very few, maybe 10% of the industry sales on a good day.

The difference from the time Jenette came in and Jim Galton arrived at Marvel, had some people come in from the outside with some enthusiasm, with some experience. Jenette had a lot of experience as a children’s magazine publisher which is what comics was presumed to be. Golton had a lot of experience as a book publisher. And they were trying to fix things.

It wasn’t really fixable at that point. It would take until the comic shop side of the business matured a little bit more. It felt livelier. Certainly, in the case of DC, Jenette very much wanted to make things better for the writers and artists. And for those of us who’d been sitting there, influenced by Siegel and Shuster, influenced by frustration at the economics of the business that’s a, “You know, I can sign on to that. Let me be part of that.”

Alex: Yeah. That’s great. Did you two immediately get along? Upon meeting, you and Jenette.

Levitz: We got along pretty fast. There weren’t a lot of young people in the place. She was very young. She came in at 28 years old, so we’re nine and a half years apart in age. There were three other young guys in the editorial side and maybe two in the production department at that point. Something like that. A couple of young women in production department as board artists, but not a lot of us.

Jenette’s description of how we bonded is, she says, I was the only person who kept saying, “No.” The editors were so scared of the strange young woman who’d arrived from Mars that no one would argue with her, and I would. We had some wonderful arguments, and we found some good solutions, I guess.

Alex: Would you consider her someone that you had learned from, kind of like in the same vein as Joe Orlando, or some of the other people you worked with?

Levitz: I learned an enormous amount from Jenette, at a very different depth than I learned from Joe. I mean Joe is a comics guy. He taught me about comics. He taught me a little about growing up as a human being, certainly too. But Jenette’s lessons were much more about how to work with people, how to manage as a leader, how to present yourself. She was a mentor in a whole bunch of ways to me in all that.

Alex: In a corporate fashion, it sounds like.

Levitz: You can’t describe Jenette as corporate [chuckles] but in a complex business world, let’s say.

Alex: I got you.

Levitz: She’s probably the least corporate person whoever ran a division of a major corporation.

Alex: Oh, I see what you mean… We did some research, were you also writing drafts of contracts around this time? And Bob Stein and writing contracts, what is there to that?

Levitz: In the first couple of years when Jenette got there, I began to basically run the administrative side of the editorial department. We used the title Editorial Coordinator at that point. That was keeping the books on deadline. As we started moving to written contracts, getting written contracts done.

It was really challenging to get contracts done by the corporate legal department because they had a lot to do, and DC historically… A, wasn’t a very important part of the company, and B, hadn’t historically used a lot of legal talent, so it hadn’t been a lot of support. It was taking forever to get contracts done, and I started to rough draft them.

Bob Stein was the general counsel for the publishing division of Warner at that point, which included DC, Warner Books, Mad Magazine, Independent News or Warner publishing services, whatever they changed their name, I don’t really remember the synchronicity.

So, I would do a rough draft of something and I would bring it up to Bob. He was terrific. He was a great teacher. We’re still good friends. He would go forward and say, “No, this word doesn’t mean that, legally. You have to use this tern in this fashion.” Or “You’d have to construct this.” Or “Did you think about this?” And I learned to write a contract.

I’m not a lawyer. I don’t pretend to be. Outside of intellectual property, I don’t know an enormous amount about the law, other than what I learned debating my son, as he learned to be a lawyer. But within the area that was relevant for us, I learned what I needed to know.

[01:05:04]

Alex: Sol Harrison as president, and Jenette Kahn as publisher, was there ever any butting of heads between the two? As one being more old school and one being more new school? Were you ever involved in any potential conflicts there? Or were there no conflicts at all?

Levitz: Conflict is a strong word. What the two had in common is they were both extraordinarily decent human beings who wanted good things to happen for the company, and they were both Jewish. Outside of that, not much in common.

Alex: Not much in common, okay.

Levitz: Sol was in his late 50s. He had no particular education. He probably went to work, straight out of high school, as a color separator in comics, for The Days of Action 1, literally. He knew the nuts and bolts, craft, mechanics of comics, extraordinarily well. He’s been an inker, occasionally. I think he lettered occasionally, over the years. Colored, occasionally. But he was not a sophisticated business person.

His idea of being supportive to the company, included being the first one in the office, and having your door open every time for whoever needed help, for whatever they might need. And probably being the last one to leave.

Jenette, usually had her door closed. Came in when she came in. Left when she left. Would throw parties in her apartment for the talent, a way of recruiting people. Would socialize with the talent. Totally interested in the creativity of the material rather than the craft of the material.

They were in a very difficult structural situation where they theoretically were equal partners in running the company, with this sort of fuzzy dividing line between them. I don’t think there was a lot of conflict per se, but there were certainly, emotional tension back and forth. It was a challenging few years, for all of that. I got along well with both of them.

Alex: So, you could relate to both.

Levitz: Yeah. I mean… Sol taught me a lot. He took me to first trips inside a newsstand distributor. First time, convention of the ID business, went along with him. First times I went to a printing plant. He was even back on the 1976 program book for New York Con. I think, I had fallen behind in the production of that, and he jumped in and helped us fulfil, to get that done.

Jenette was certainly the one who was more influential in developing me as an executive and giving me more responsibility and more free-reign. But got along with both of them. Both of them taught me.

Alex: That’s cool. That’s cool that you were kind of this sounding board and sponge of people like Joe Orlando, and Harrison and Kahn. It sounds like that was a super formative time.

Levitz: I did an article once, Alex, or a web post… I don’t remember where it is. Where I described as being bat boy young to the Yankees when it was murderers’ row. The office at the time… Think about this for a second, with some distance.

In whatever, the first five or so years I’m there: Carmine Infantino, Sol Harrison, Jack Adler who invented many of the color systems that we used in the comics in those years. Julie Schwartz, Murray Boltinoff who was an editor for the company from 1942 or so. Joe Orlando, Joe Kubert, Archie Goodwin, Denny O’Neil. Joe Simon’s technically an editor, he shows up once in a while. A couple of those guys hadn’t made it to the Hall of Fame, any of them you could argue, reasonably could or should, and most, have made it to the Hall of Fame.

How do you not learn from those people?

Alex: Yes, it’s incredible.

Levitz: There’s no dead weight on that side of the equation.

Alex: Yeah. They helped build this industry… In ’78… you were editing since ’76, and in ’78, you became editor of Batman comics following Julius Schwartz. Did you have a vision of Batman, at the time going into that? Tell us about that transition.

Levitz: After the implosion, we had to juggle the editorial assignments. Part of the logic that was decided on was that we should have a single editor for each of the major characters. Julie, being Julie, he was given his choice. There wasn’t enough room on his schedule for him to do both all the Superman books and all the Batman books. “So, which one do you want?” He picked Superman.

I actually think that was the wrong choice for him because I think he was a better Batman editor than a Superman editor in the course of his life. But he felt that was the more prestigious assignment, and particularly, we’re coming up on the Chris Reeve movies, so there’s a lot of logic to it in that point of view.

[01:10:06]

I got the next dibs so I got Batman. I was much more a Superman reader than I was a Batman reader growing up, but I’ve read and enjoyed a fair amount of Batman. Thought he was a good character. So, I went in the library, basically took all the Batmans, from the beginning, and either read or reread them, and wrote, what I believe is the first time DC ever had a character bible for one of the characters. So that I could have all the writers on the same page at the same time.

Alex: Wow. That’s awesome. Because that brings a lot of order to the chaos.

Alex: As you mentioned him, what is your impression of Julius Schwartz. He was there for decades, obviously. Were you fond of him? Did you like him? What’s your impression of Julius Schwartz?

Levitz: I liked Julie a lot. I learned an awful lot about organizational methodology for comics from Julie. Record keeping, administering in keeping things on deadline. He was terrific at that side of the job. When he finally asked me to write for him, around ’78, that’s the first time I felt I really was a professional writer.

Alex: Oh, cool.

Levitz: Getting assignments from Joe or from Gerry, I was there in the middle of it. I was in a privileged position, which I either used or abused, [chuckle] probably both at different points. Julie offering me an assignment was a real editor saying, “You’re worthy. Take a shot.”

Jim: And that was DC Comics Presents, right?

Levitz: Yeah. Yeah, I did a few of those… Julie’s role in making the comics more intelligent, and more sophisticated, in the early ‘60s, the whole creation of the second heroic age, if you will, the Silver Age, is a tremendous contribution to the field.

Levitz: He stayed a long time, maybe the last few years, he wasn’t as in tuned with the market as he was earlier on. Other challenges of age crept up, and there are things that make his legacy more complicated from those years. But if he had done nothing but the work he did, from 1956 to 1964, he would be one of the three or four most important editors comics ever had.

Alex: Yeah, of all time. Industry changes around this time… Jim Shooter became editor in chief, in ’78 in Marvel, and there was some friction he had. People like Roy Thomas, Gene Colan, moved over to DC. Jim Starlin, also moved over to DC when this is happening. What was your impression, just of down the street, “Oh, what’s going on over there that all of these people are coming over?” Did they express their impression of why they left, to you? What was your impression on what was going on with that shift?

Levitz: That would be…?

Alex: … ’80, ‘81 at this point.

Levitz: Yeah. Because from ’76 to ’80, I have a regular poker game going. It includes Jim, Len Wein, Marv Wolfman, Denny O’Neil, occasionally Chris Claremont, occasionally, Frank Miller, Marty Pasko, Jack Abel, Steve Mitchell, Roger Slifer. There was a lot of cross-company …

Alex: Camaraderie.

Levitz: Camaraderie, friendly relationship.

Jim’s one of the best editors of comics. Probably one of the three best editors of my generation. I’d argue he was a better editor than I was. He had, I think two challenges, one, the editor in chief title is intrinsically a two-edged sword for a talented person.

When you take responsibility for a whole line, of the size Marvel was, or the DC was, if you approach the editor in chief role as saying, “I am responsible for each and every one of these books! I will make it right!” That’s enormously draining. If you’re good enough to do it well, I think, it either damages you emotionally, or damages you physically.

Shelly Mayer who did that back on the All-American Line, back in the ‘40s, who I think was an extraordinary editor as well, pretty much destroyed his health in the process. It’s a major part of why he retired from that as a very young man, to return to being a cartoonist, which is what he loved, for the rest of his life.

Jim, I think, damaged an awful lot of his emotional relationships with a lot of people. And I think the other problem with it is, if you’re that good as an editor in chief, and you start fixing everything that’s around you, your subordinate editors begin to create to your desires, and to your needs, or trying to double think, “What will the boss think of this?”

It was the reason I never took the editor in chief title, when I had the opportunities to. I think I would have been vulnerable to exactly the same thing.

[00:05:06]

Jenette, never had that kind of problem because she was not a comic book writer or editor at heart. So, she never took possession in the same way. Her view of being editor in chief, which is perfectly valid, was to be the guiding spirit, and the cheerleader for it all. Setting basic policy, basic direction, but not reading every book.

Jim would read every issue of Marvel before it went out. Make notes. Have things fixed. Require a change in an ending on an important story. He arguably was right 90% of the time. But it’s very difficult thing to maintain your relationship with the creative people when you’re doing that.

Some of the people you’re talking about didn’t leave Marvel because of anything to do with Jim. Jim Starlin, I think had enormous frustration with Marvel, over the way they approached the change in the copywrite act in the late ‘70s, and walked away because he didn’t agree with their contracts at that point. That’s nothing Jim had any control of over.

Alex: Right. True.

Levitz: Some of the other people, were just ready for a change. Some left because of some frustration with their editors. We lost some people because of their frustration with editors at DC too. There was certainly a period, for a couple of years there, where Jim was having a rough time with the talent pool.

Alex: Right. And also, the people kind of went back and forth, because like you mentioned, the DC implosion, people like Tom DeFalco, and Larry Hama moved over to Marvel just because of there just wasn’t as much work at the time. I guess, there’s various reasons for these shifts in talent.

In ’81, Sol Harrison leaves DC Comics, as president, he left. Was this a planned retirement? Were there other factors in his leaving? Or was he like, “I’m just done. I’m just tired.” What led to him leaving?

Levitz: He was 60 years old. He’d been there since the beginning of time. Give the guy a break. Let’s count it as retirement.

Alex: Right. So, just a pure retirement… So then, Jenette became both the publisher and the president and then you became… I want to get this title right, because I saw on one article, is DC’s Manager of Business Affairs, but is that now called Chief Operating Officer? Are these correct titles?